Post contributed by Colette Harley, Graduate Student Intern, Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture.

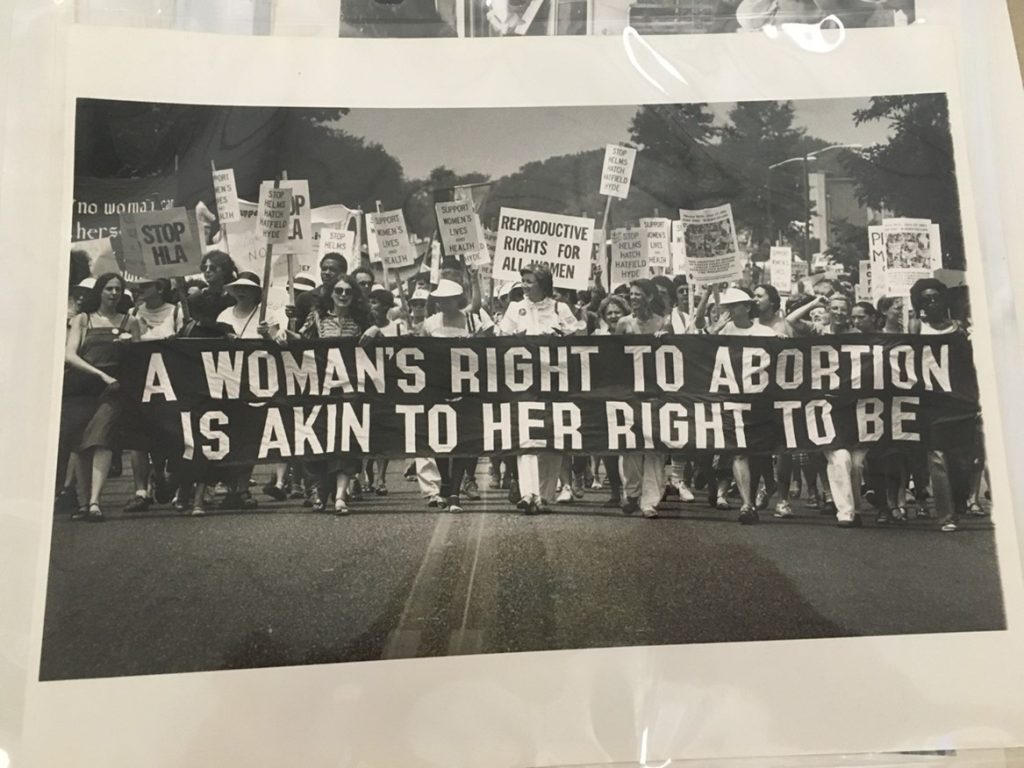

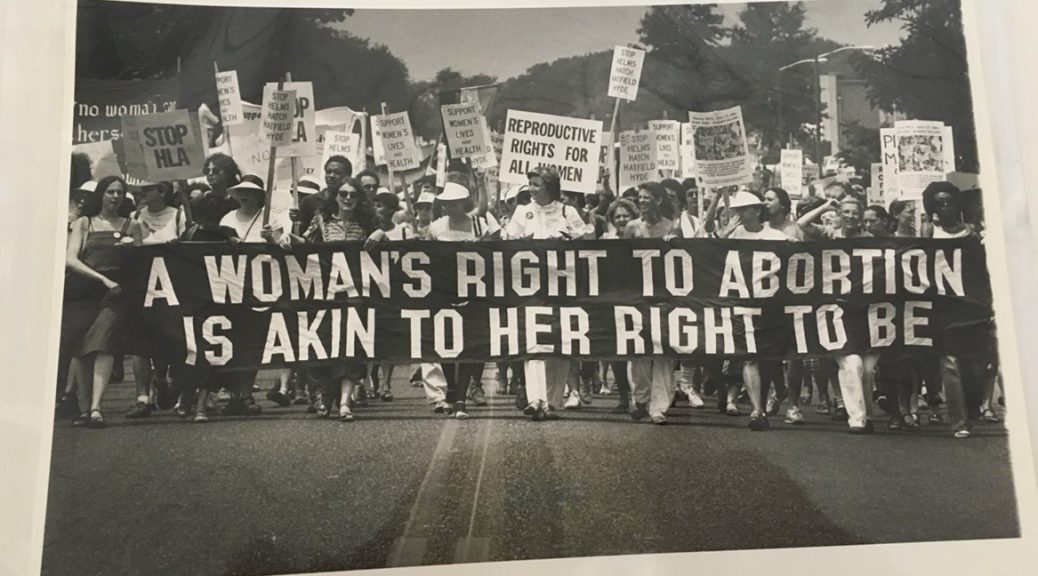

In March of 2024, I read an article about a woman named Julie Burkhart. The article detailed Burkhart’s challenges in opening an abortion clinic in Wyoming, one of the states with the strictest abortion laws in our post-Dobbs era. Burkhart was an employee and mentee of Dr. George Tiller, and worked in his clinic in Wichita, Kansas. Dr. Tiller was shot on two separate occasions by anti-abortion protestors, and his clinic in Kansas was the site of extended protests during the 1991 Summer of Mercy. The Summer of Mercy, organized by the anti-abortion organization Operation Rescue targeted abortion clinics and patients seeking care. This article piqued my interest—for all my knowledge about reproductive rights in America, this was not something I was familiar with. It had a strange sort of prescience, given our current political climate towards reproductive rights.

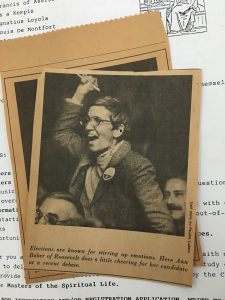

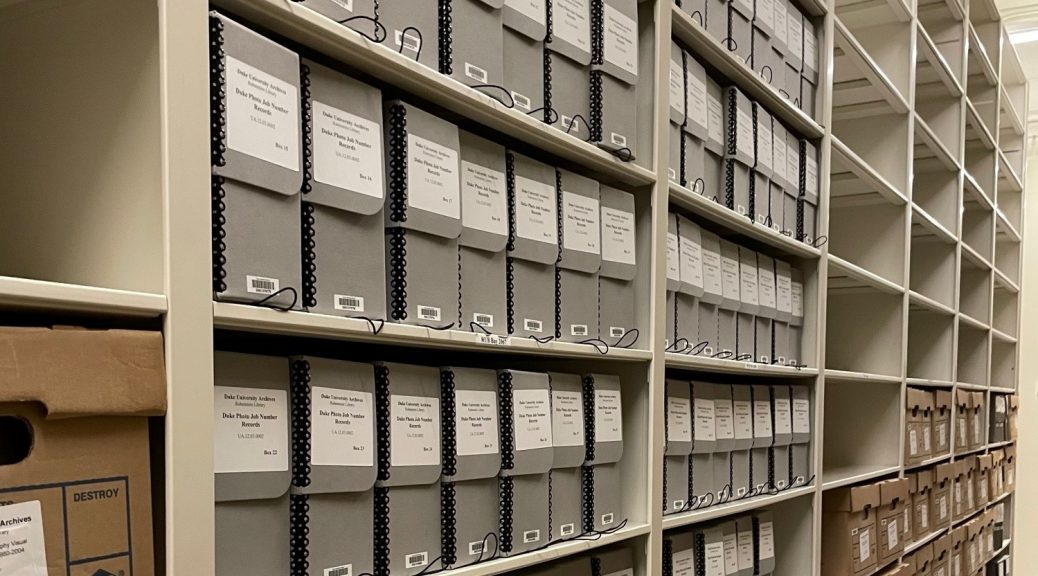

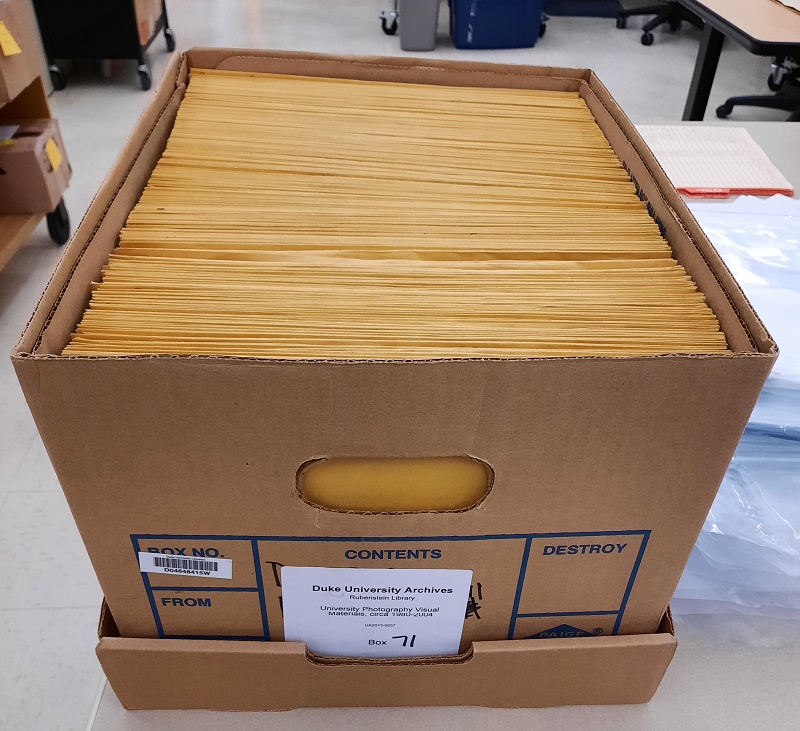

It was a strange sort of kismet a few months later when Laura Micham, Director of the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture, suggested I consider processing the papers of a woman named Ann Baker as my next project. Fresh off of smaller processing projects, the 130 linear feet were daunting. Packed by Ann’s widow and friends, the collection arrived on the Bingham ranges in a variety of boxes—some standard sizes, others repurposed from moves and office supplies. At the time, I knew Ann was from New Jersey and that she was a reproductive health and LGBT rights activist. What I didn’t know was that she focused her work on the impact of Operation Rescue and other pro-life organizations during the 1980s and 1990s.

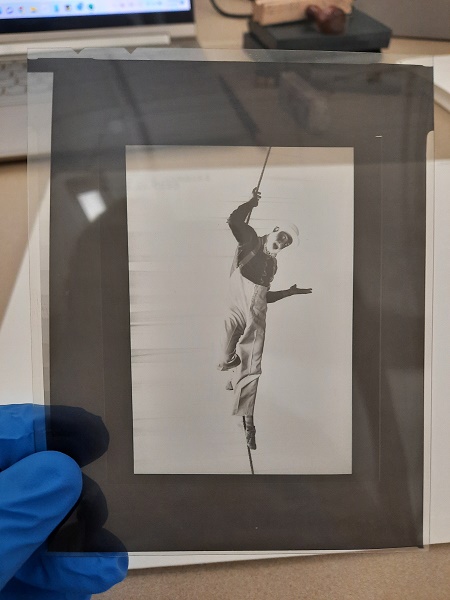

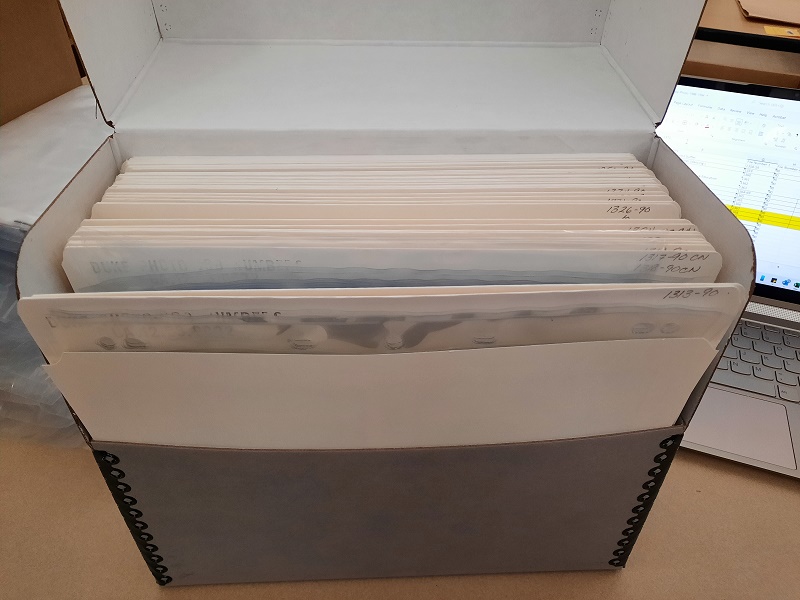

As Laura and I surveyed the boxes, a picture started to slowly unfold. Baker’s organization, the National Center for the Pro-Choice Majority (originally the 80% Majority), served as a clearing house for information on anti-abortion protestors and tactics. Each week, Baker would compile arrest lists (sometimes provided by police departments, clinics, and local newspapers) for the different demonstrations that happened across the country. She would then cross-check with previous arrests to determine if any person had been involved in this kind of event in another city or state. As it became apparent that the same groups of people were involved in these “rescues” week after week, law enforcement began increasing fines and jail time for repeat offenders. The national movement against abortion, the scale of which was promised by leaders like Randall Terry and Joe Scheidler, turned out to be little more than a small group of devoted followers.

Baker documented the protestors, their tactics (such as chaining themselves to blocks of concrete inside the clinic), and their propaganda. She collected newspaper clippings, literature, policy books and reports, and dossiers of protestor information. She even subscribed to some of the more militant publications using money orders, fake names, and P.O. boxes. She tracked lawsuits that ranged from husbands and boyfriends suing their wives and girlfriends for seeking abortion, to Frisby v. Schultz, which made residential picketing of abortion providers’ homes illegal. Armed with this information, she wrote about these organizations in her newsletter, The Campaign Report, which was mailed to clinics, providers, and activists across the U.S. In this newsletter, she tracked the many tendrils of the pro-life movement, provided information on what clinics could expect to see when Operation Rescue came to town, explained how to work with local law enforcement, and offered analysis about politics, the U.S. government, and citizens’ attitudes toward abortion.

Baker was a diligent filer. Many of the folders were titled and organized loosely by theme. The most difficult part was keeping track of all the different threads I’d found throughout this very large collection. Some of the original order of the collection needed to be fine-tuned for it to be easier for current researchers to use, but I kept all of her original folder titles. As I spent more time with her work, I gained a sense of her personality. One of my favorite aspects of the collection was the marginalia, whether it be complaints, frustrations, or New York Knicks scores scrawled in the margins. She had a penchant for argument through the written word, and some of my favorite letters she wrote had nothing to do with the pro-life movement at all. In one folder, I found a copy of a parking ticket, annotated with a note in which Baker insisted that paid parking should only extend through normal business hours.

I am deeply thankful to Baker and her work, as well as the other activists, providers, and clinic workers documented in this collection. She noticed a gap: no one was tracking the protests state by state, and she took it upon herself to fill that gap. Through this work, she provided clinics with the information they needed, whether it be organizing tactics or information on protestors. She built a deep network of contacts, many of whom are also represented in the Bingham Center’s collections. She is not a household name, but she is a reminder that to make a difference, one does not need to be.

Processing archival collections is iterative, exacting work which often requires circling back through materials again and again. I went through this collection many times, moving materials into different series, trying to decide how they best made sense. In the thick of it over the summer, I had a sense that I’d never be finished. But slowly, day after day, it came together. I’ve been thinking often that it takes a village to process an archival collection, and I’m deeply thankful to everyone in Technical Services and the Bingham Center for their knowledge, expertise, and cheerleading. I believe this collection will be a valuable body of material for researchers looking to understand not only the period in which Baker did her work, but also our current era in which reproductive rights remain precarious.

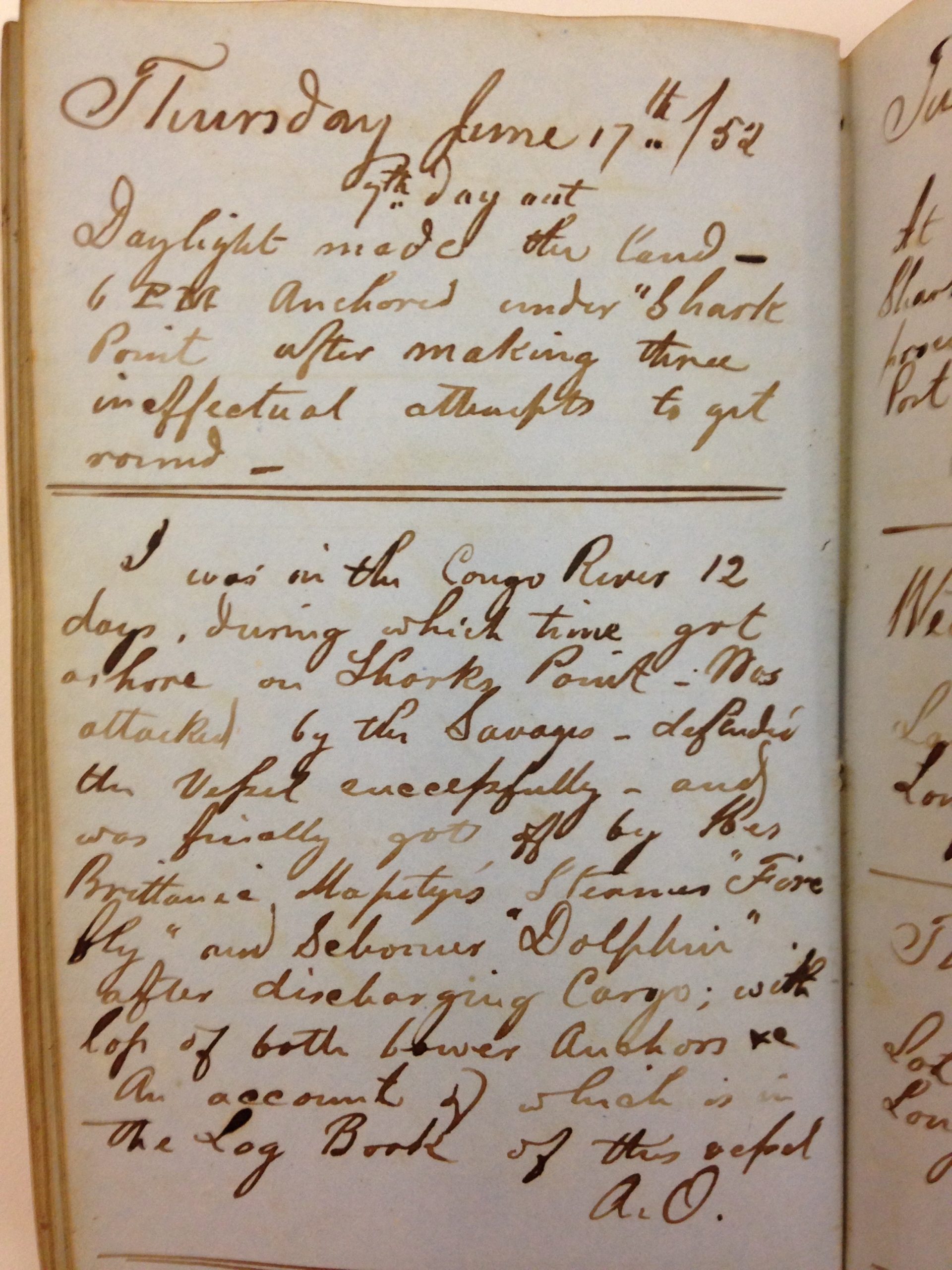

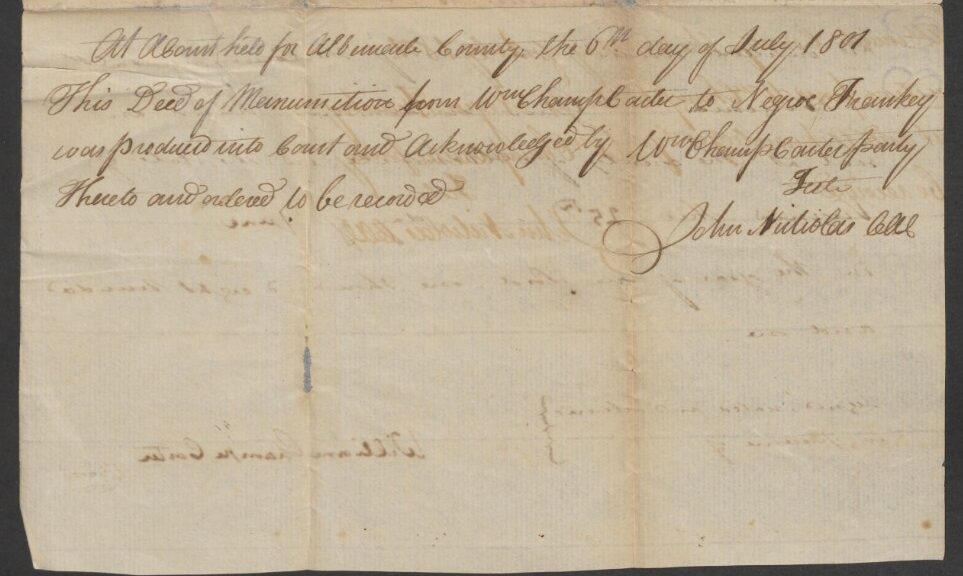

![Transcript of recto: To all whom these presents shall come, know ye that for divers good causes and considerations me hereunto moving, but more especially in consideration of the sum of forty two pounds to me in hand paid by Lott (the waggoner) who was liberated by my deceased father Edward Carter, esq., as well as in consideration of the meritorious services of she, the wife of the said Lott, named Frankey, I have emancipated and set at liberty, and by these presents do emancipate and set at liberty my said negro slave Frankey, giving her all the privileges and [?] to which emancipated slaves are entitled under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, given under my hand and seal, at the county of Albemarle, in the state of Virginia, this 25th day of June in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and one. Signed, sealed, and delivered in the presence of [blanks for witnesses] William Champe Carter Hand-written record of emancipation](http://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2020/12/Frankey_Deed_of_Manumission.jpg)