Post contributed by Stephanie Fell, Rare Materials Project Cataloger

When the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection was packed and shipped to Duke in early 2015, many of the materials were boxed thematically. Therefore, as we have been cataloging the collection, the materials tend to come in waves of various themes and subject matter. Lately a number of cookbooks and monographs relating to domestic arts have been coming across my desk. Some have been traditional cookbooks and domestic arts manuals, offering recipes, menus, and nutrition information, as well as advice to the home maker, from cooking, cleaning, and child care tips to household budgeting and how to decorate the home. I wanted to point out a couple of items in particular that caught my attention.

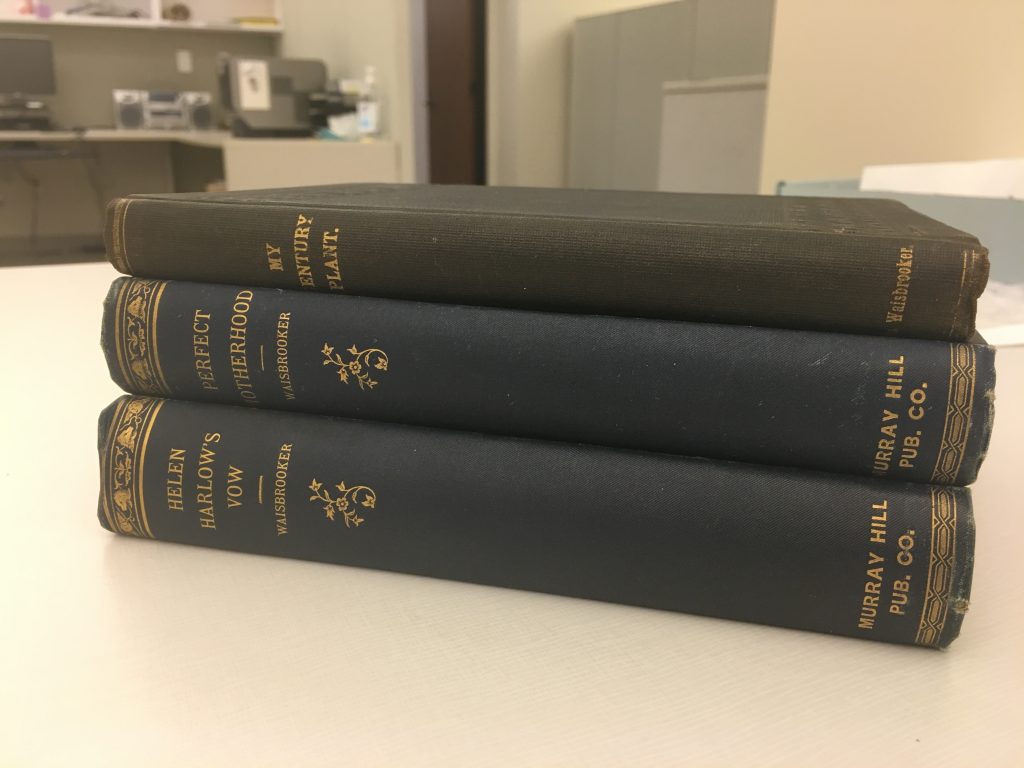

These particular books, at first glance, are traditional cookbooks or domestic arts manuals for women to help them maintain a healthy and happy home through cooking and good housekeeping. Looking more closely, however, they contain a subversive message that rejects traditional gender roles and encourages the reader to emancipate herself from the kitchen.

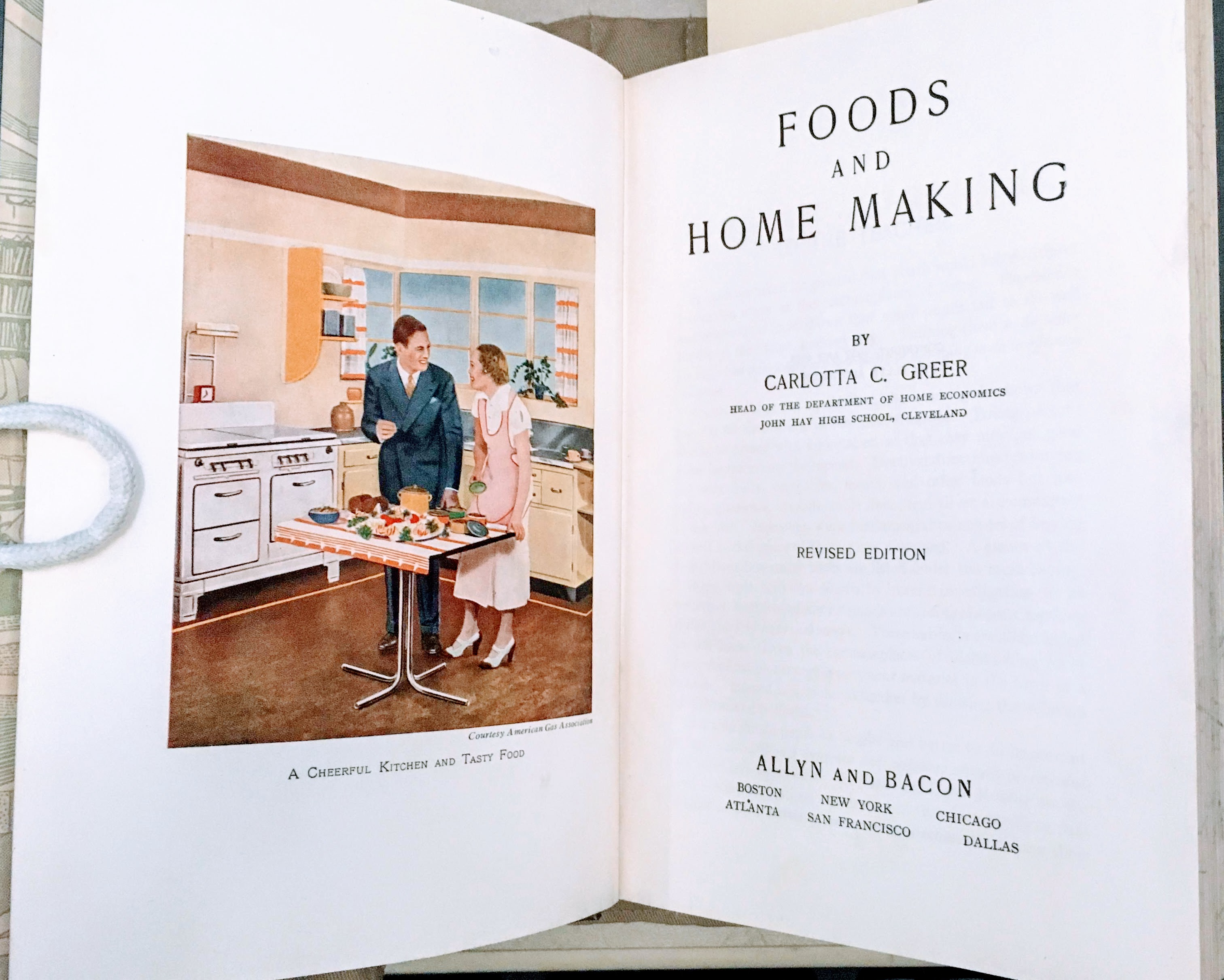

Foods and Home Making by Carlotta C. Greer, published in 1938, was intended to be used by teachers to train boys and girls to do household tasks better. This text looks typical of the genre and time period; it includes “many suggestions and devices to stimulate pupils to participate in home activities and to do their share in making their homes attractive and happy” (page iii-iv). Upon closer examination, the “To the teacher” note includes the following advice: “Much of the material of Foods and Home Making is suitable for boys as well as girls. Knowledge of food selection is necessary for boys. Stimulation of boys’ interest in home making contributes to their appreciation of home life” (page v). The author encourages the reader to get her sons involved (and appreciate!) the work involved with sustaining and maintaining a household.

Another noteworthy feature of the Rubenstein Library’s copy is that it contains manuscript annotations indicating the owner was using the volume to prepare for an exam. Part of my work as a rare materials cataloger is to include provenance-related information such as this in the library’s catalog record in copy-specific notes. This kind of information about the book is important to include in the bibliographic record, because it shows not only how a former owner used the item, but also helps to differentiate this copy from copies at other institutions.

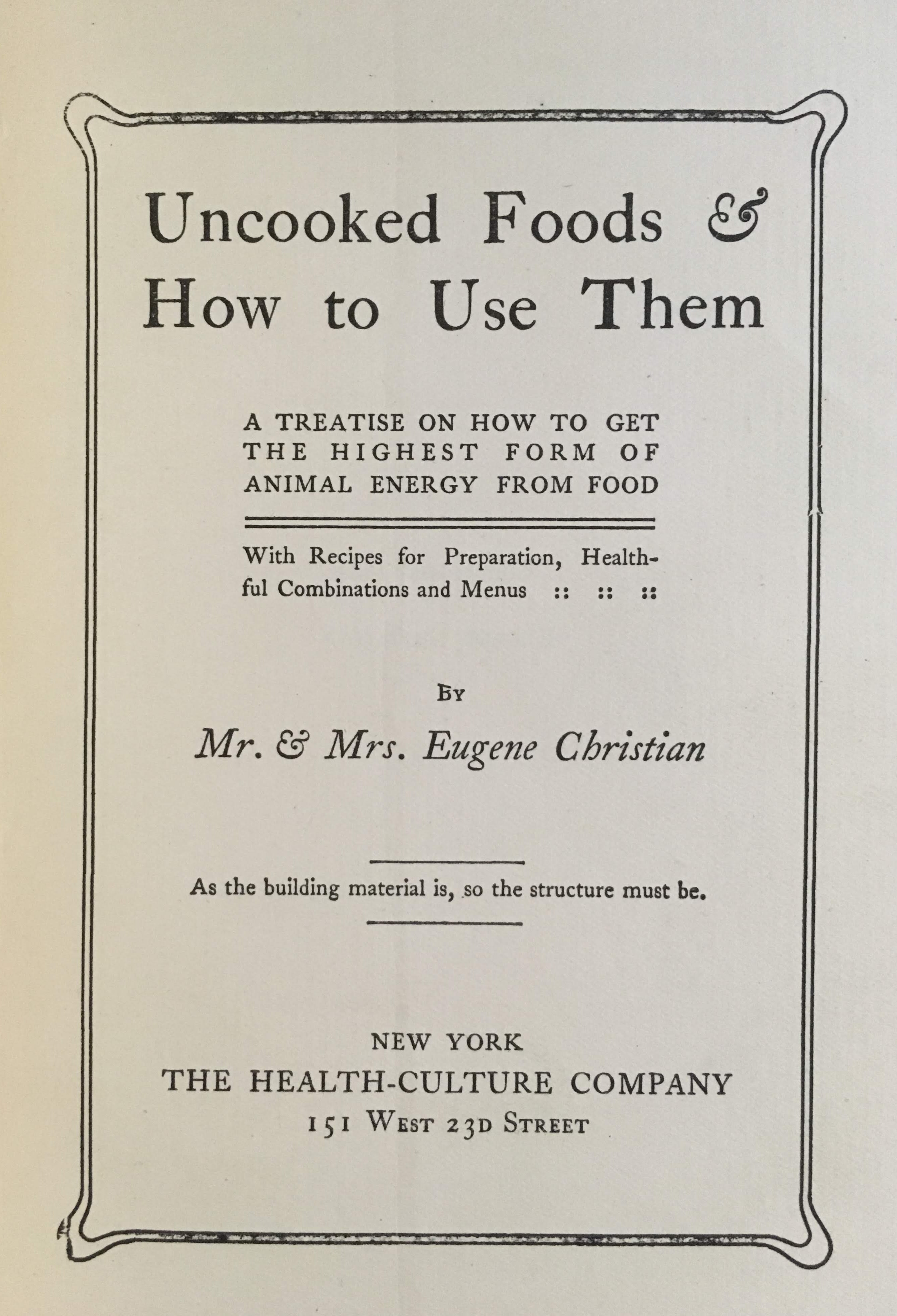

Another volume I cataloged recently is Uncooked Foods & How to Use Them by Mrs. & Mrs. Eugene Christian. Published in 1904, it is dedicated to “the women of America on whom depend the future greatness of our glorious country”. This unassuming volume includes more than just recipes and housekeeping advice. Scrolling through the table of contents, the reader will find that chapter 8 is entitled “Emancipation of Woman”. The authors advocate a raw food diet — one reason for this being simplicity: “There is nothing more complicated–more laborious and more nerve-destroying, than the preparation of the alleged good dinner. There is nothing simpler, easier and more entertaining than the preparation of an uncooked dinner” (page [39]). The authors argue that eating raw foods is healthier and will “emancipate [the reader] from the slavery of the kitchen and the cook stove” (page [49]). They continue, “… the use of uncooked or natural foods will surely bring relief and freedom” (page 52). Mr. and Mrs. Christian were admittedly ahead of their time in more than one regard.

As I’m cataloging the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, which documents the work of women over the last 500 years, I’m not just describing the materials bibliographically, but I’m also trying to provide relevant access points and descriptive information for researchers. In addition to these items, the Rubenstein Library holds many other volumes related to cooking and domestic life. One can find other examples of domestic arts advice for women both inside and outside of this collection through Duke University Library’s online catalog. A genre term search for “Cookbooks” will return many items in that category and a keyword search for “prescriptive literature” may yield broader results.

Few anarchists have gained as much mainstream recognition as Emma Goldman, an iconic figure in labor organizing, feminist history, and prison abolition. The

Few anarchists have gained as much mainstream recognition as Emma Goldman, an iconic figure in labor organizing, feminist history, and prison abolition. The

The

The