Post contributed by Rachael Brittain, Harry H. Harkins, Jr. Intern for the Duke Centennial at the Duke University Archives.

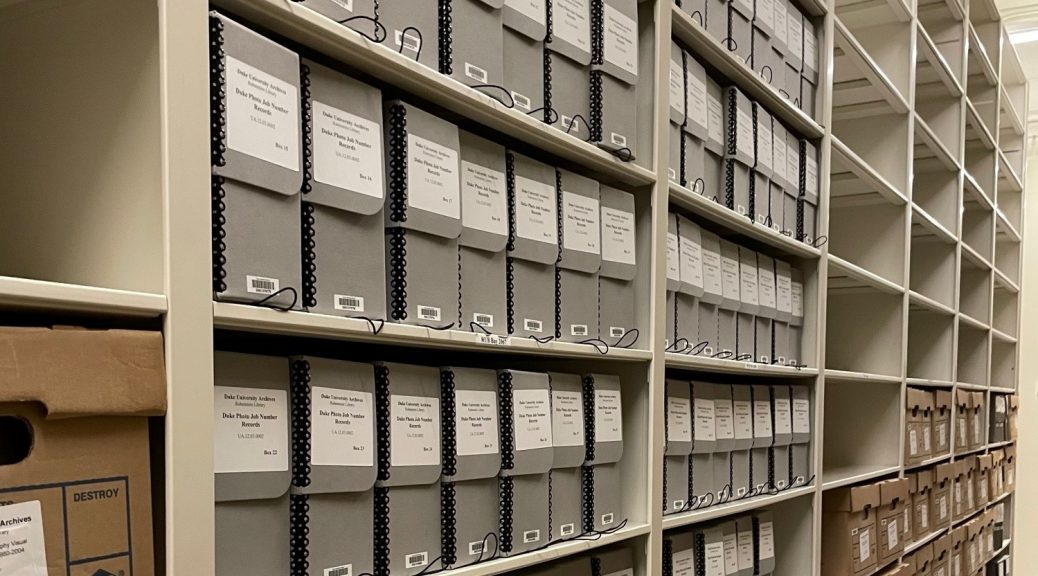

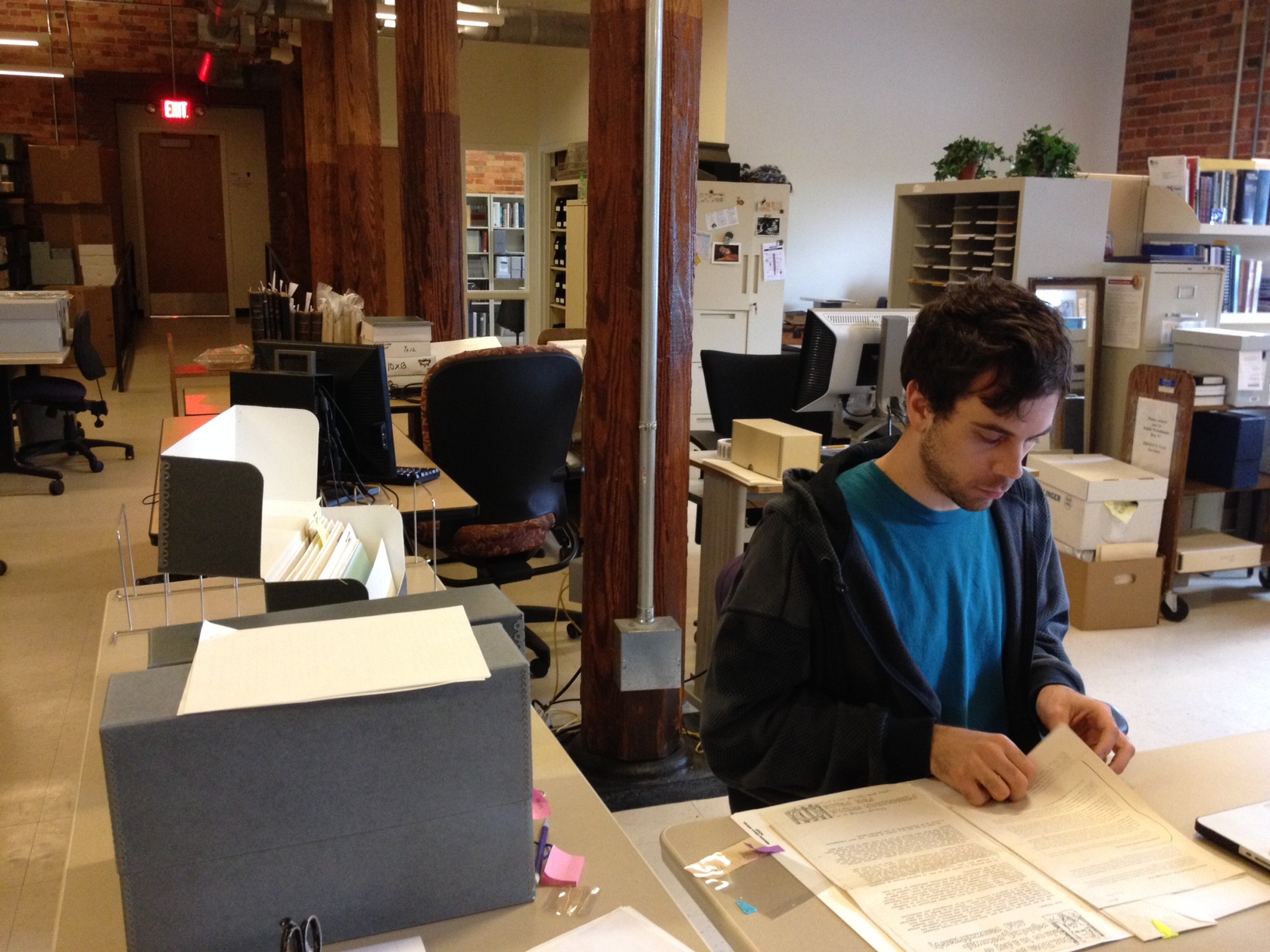

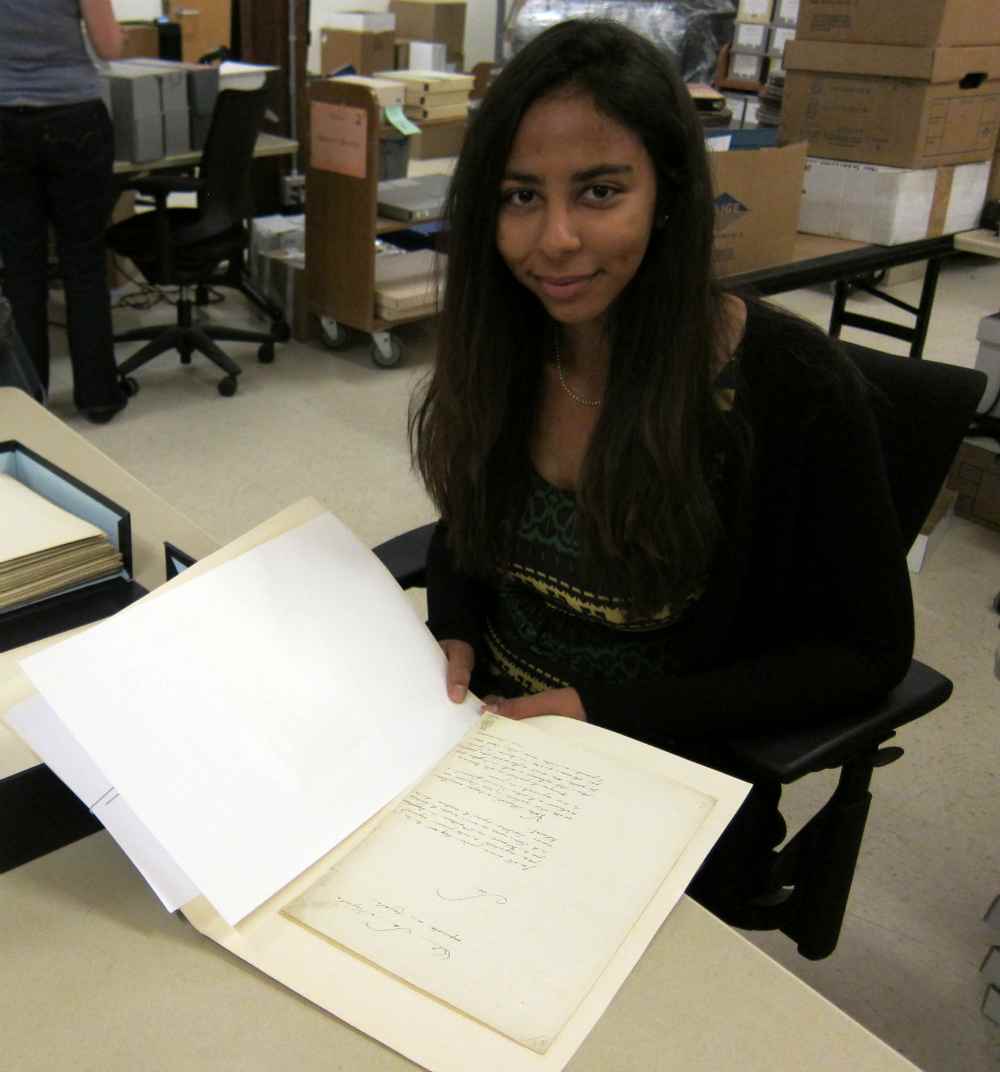

As the Harry Harkins Intern, I have been working with the Duke Photography collection to rehouse materials; assist on reference questions; create timestamps for archival films; and help identify collections at Duke related to its early history. My primary focus has been the Duke Photography Job Numbers Collection. which contains original photographs taken by Duke Photography from 1960 until 2018.

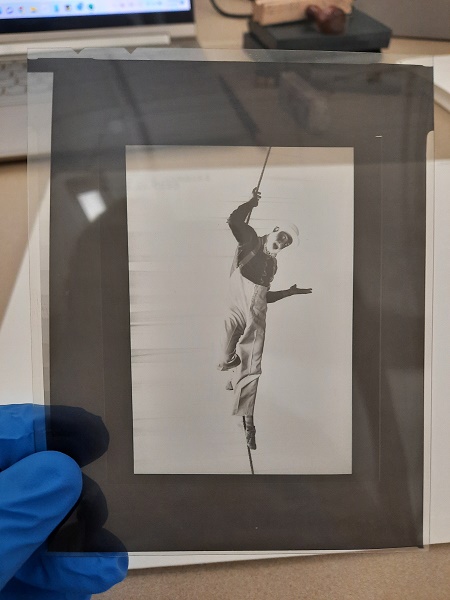

Capturing unique images and perspectives of Duke University as well as operating as a hired service to photograph faculty, staff, and student headshots, Duke Photography was present at many major university events, including basketball, lacrosse, football, and other athletics; visiting lecturers and guest speakers; building construction and grand openings; campus scenes, and other aspects of campus life at Duke. The time frame that Duke Photography was active means that there is a mix of analog and digital files, switching to primarily digital in the early 2000s.

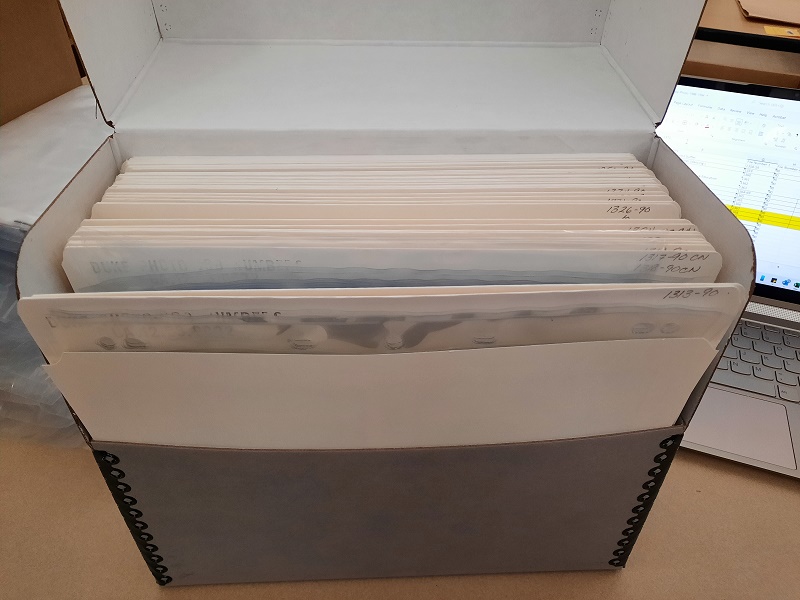

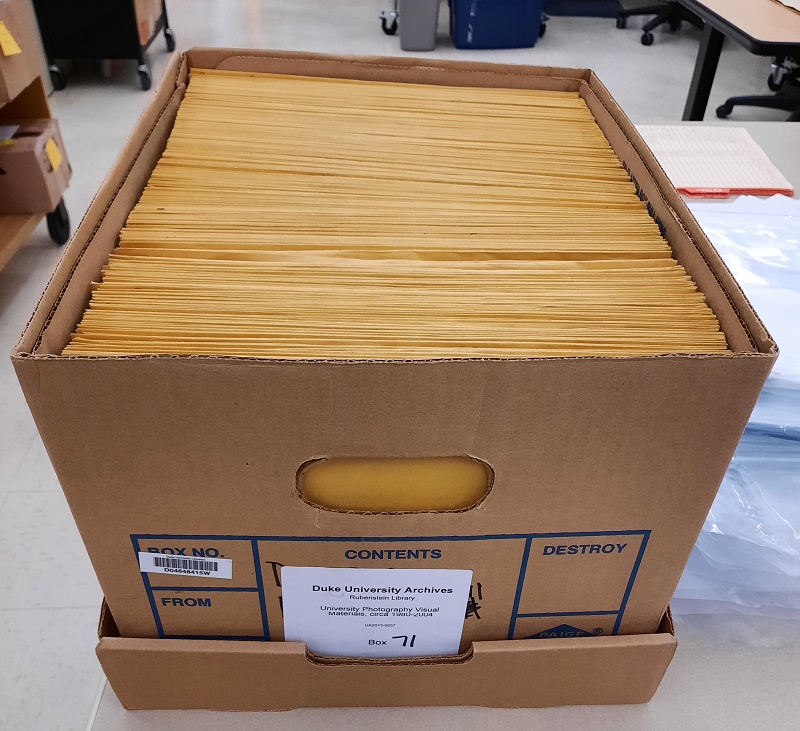

As the University prepares for the 2024 Duke Centennial, we wanted to make sure our photograph collections were as accessible as possible. The years between 1988 and 1994 have presented a unique challenge as many of the images are stored in old manila envelopes, some of which are missing. The manila envelopes are a less than ideal way of storing photographs and negatives due to the amount of acid present in the envelopes. Eventually, this would cause the images to yellow. The items stored in these envelopes must be rehoused into safer, archival materials. Across 28 boxes and over 11,000 manila envelopes, I have found 35 mm, 120 mm, 4 x 5″ negatives, contact sheets, prints, and occasionally slide film.

The variety of materials used by the photographers largely depended on the purpose and printing needs of the subjects. 35 mm film, both black and white and color, was standard for most events due to its ease of use and availability. 120 mm film, also in black and white and color, produced a larger negative allowing the photographers to print larger, with greater detail, and with less film grain (a granular texture that is left on film when over enlarged). 4 x 5” negatives created an even larger negative and were frequently used to make copies of images. Once an image was printed from 35- or 120-mm film and corrected properly, it was faster for photographers to photograph the final image and print from the new negative, creating a copy negative, these make it faster and easier for an image to be reprinted at different sizes and at a consistent quality.

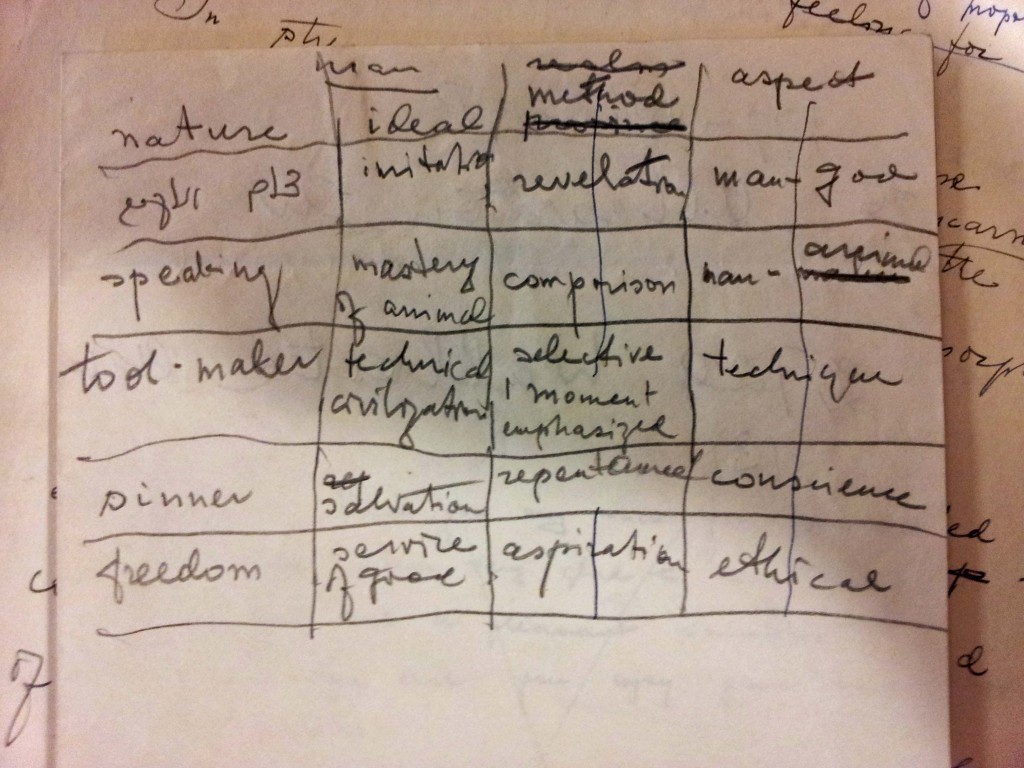

Negatives need to be stored in specialized plastic sleeves to keep them organized, protect them from fingerprints, dust, and getting scratched, all of which would permanently damage the images and make future use more difficult. Contact sheets—which were created by laying an entire roll of film across a page and helped the photographers to get a quick glance at what photos were on the roll of film and determine which they wanted to print—are being transferred to acid free folders. When more than one page or print is in an envelope, plastic sleeves are used to keep them separated and prevent scratches. This will also make it easier for future researchers and library staff to use the folders without having to use gloves to handle the materials. The Duke University photographers would make contact prints and send them to the different Duke departments so the subjects themselves could select which images they wanted printed.

As I’ve processed the collection, I’ve noted that not every envelope contains prints, as the prints were usually sent off to whichever department requested them. However, there are occasionally black and white prints, done in-house by Duke as well as envelopes full of 3.5 x 5” color prints that came from specialized color printing labs. Occasionally, there are notes left in with the photos, stating who is in each frame, what the event was for, letters requesting images, and notes scribbled on the back of event programs. By capturing events, staff, and students, this collection provides visual documentation of Duke’s recent history and will be made accessible through improved storage and descriptions.