Post contributed by Meghan Lyon, Head of Technical Services

The “Duke University Libraries Statement of Our Commitment” (issued in June 2020) commits Duke Libraries to expand our cultural competence and combat racism. The statement offered five goals (summarized below) as a means of upholding that commitment:

- Dismantle white privilege in collections and services.

- Diversify our staff.

- Develop better relationships with community organizations and groups.

- Document and share Duke’s complex institutional history.

- And finally, “practice more inclusive metadata creation, with the goal of harm reduction from biased and alienating description and classification.”

Creating “Guiding Principles” for RL Technical Services

The Rubenstein Library Technical Services Department has been seeking to create “inclusive metadata” for much longer than the summer of 2020, but we have recently been inspired by Duke Libraries’ “Statement of Our Commitment” to more formally and concretely define what “inclusive metadata” means. We began this process by collecting and reading library and community literature, listening to panels and presentations on these topics, and researching what our peers and role models are doing. Our staff met and workshopped a draft of new “Guiding Principles for Description,” which was subsequently edited and adopted by the department and is now available here (along with links to some further reading and references):

The Rubenstein Library Technical Services Department acknowledges the historical role of libraries and archives, including our own institution, in amplifying the voices of those with political, social, and economic power, while omitting and erasing the voices of the oppressed. We have developed these Guiding Principles for Description as the first step in our ongoing commitment to respond to this injustice.

-

-

We will use inclusive and accessible language when describing the people represented by or documented in our materials. We commit to continually educate ourselves on evolving language and practices of inclusivity and accessibility.

-

We will prioritize facts and accuracy, and resist editorializing, valorizing, or euphemistic narratives or phrases in our description. This includes a commitment to revisit and revise our past description.

-

When describing our collections, we will purposefully seek and document the presence and activities of marginalized communities and voices.

-

We welcome and will seek to incorporate input and feedback on our descriptive choices from the communities and people represented by and in our materials.

-

We will be transparent about the origin of our description, and our role in adding or replacing description. We will also commit to increased transparency about our own institution’s past descriptive practices.

-

We will advocate for and celebrate library description, and the essential labor and expertise of the library practitioners who create and maintain that description, as crucial for any ongoing preservation of, access to, and research within library collections.

-

Developing this list of guiding principles is only one part of our ongoing commitment to create inclusive description of Rubenstein Library materials. Our department processes and catalogs a wide range of special collection formats (printed books, serials, ephemera, zines, archival papers, institutional records, film, video, born digital files, objects, and more) and creates description that is shared across a variety of platforms like the library catalog, finding aid database, and Duke’s institutional repository. Going forward, we hope the “Guiding Principles” will serve as the foundation for any type of description created or managed by Rubenstein’s catalogers and archivists.

Current and Future Inclusive Description Projects

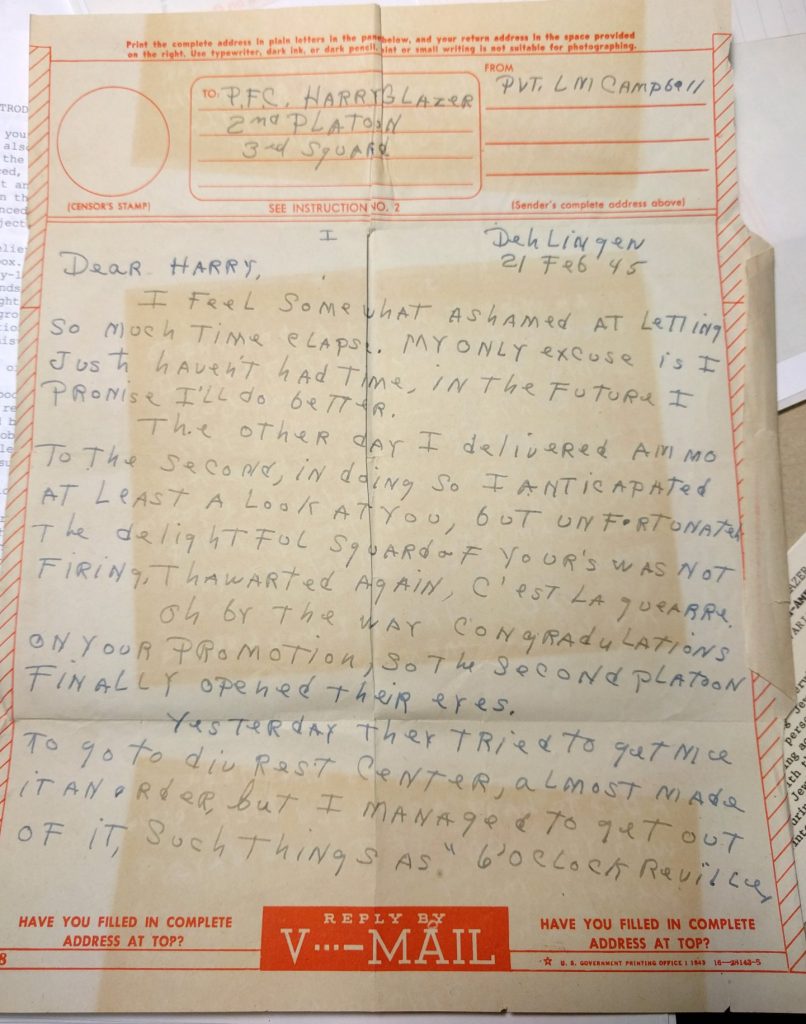

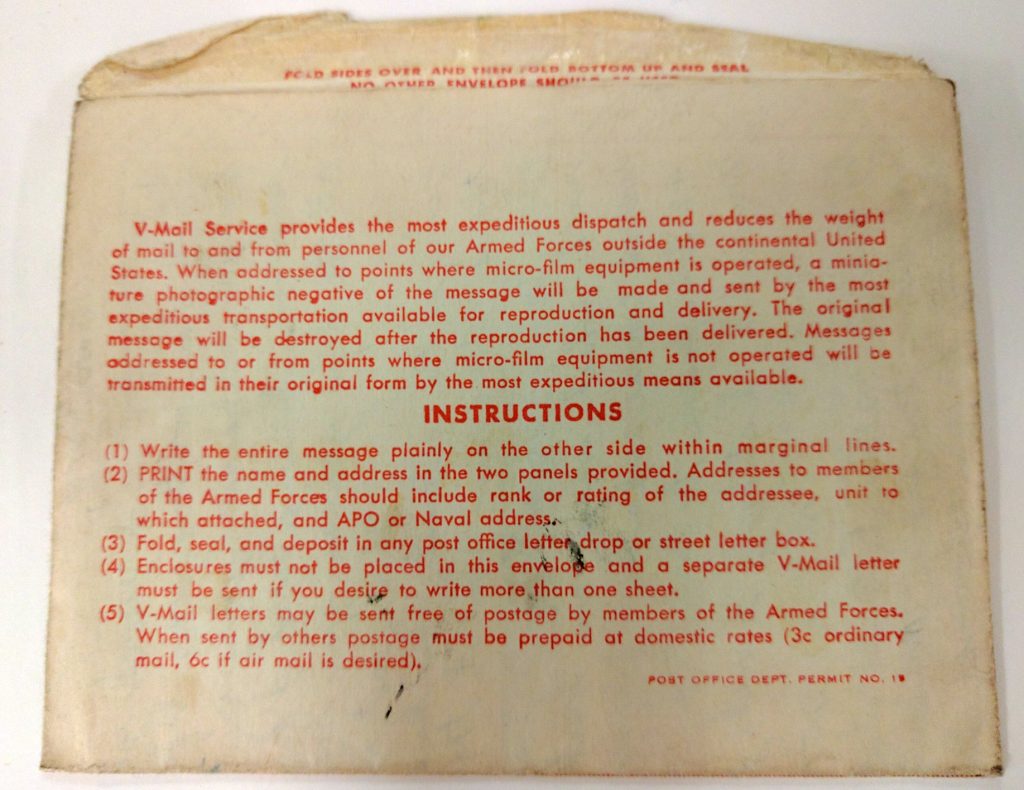

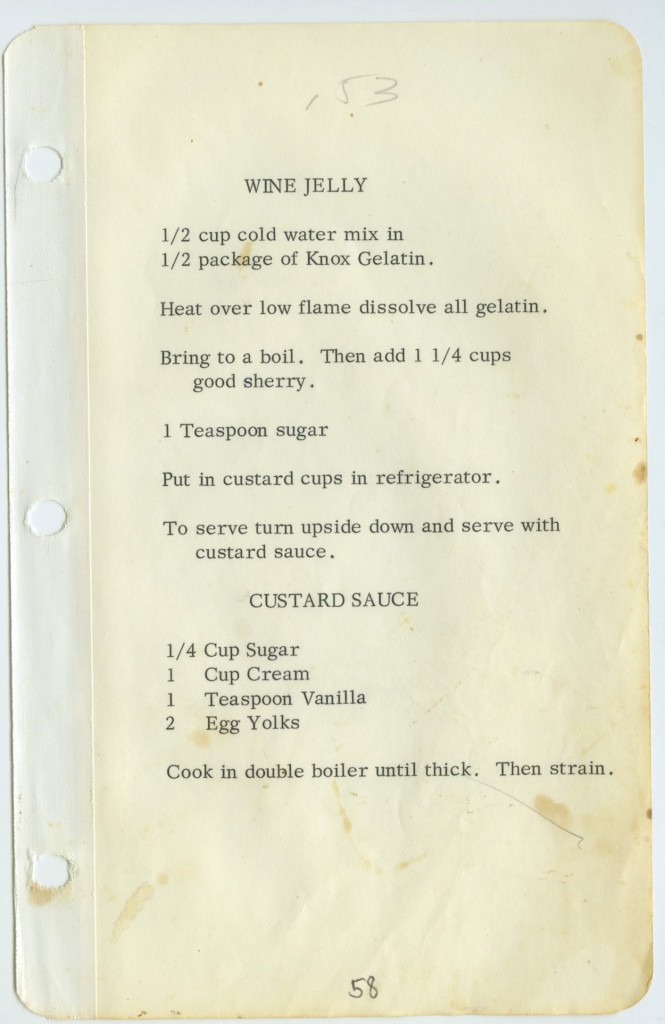

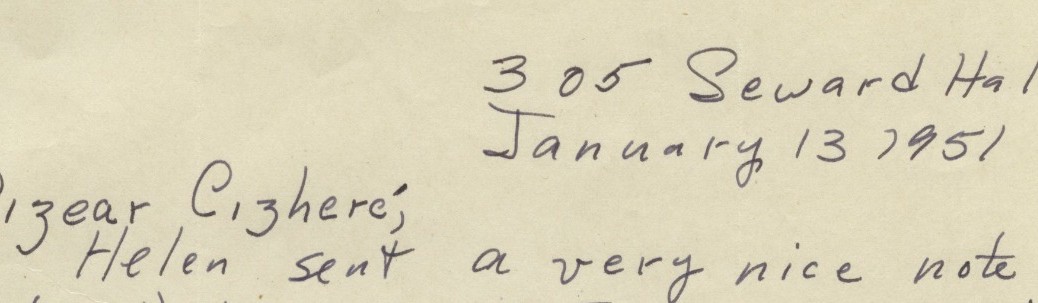

There is much work already underway, and much more planned as Rubenstein Technical Services continues to prioritize the creation of inclusive description. Some of these projects pre-date the coining of our “Guiding Principles” — for example, we are proud of the ongoing cataloging of the thousands of items in the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, where catalogers are creating name authority records and detailed provenance notes tracing the often hidden role of women in printing, publishing, and book-binding. Our work to preserve and digitize film, including creating detailed description for collections like the H. Lee Waters’ Movies of Local People, have ensured the preservation and availability of community histories. When developing ArcLight, our finding aid interface (just launched in July), an important feature was the addition of a feedback button to encourage suggestions, particularly if a user spots harmful or incorrect descriptive language in our metadata.

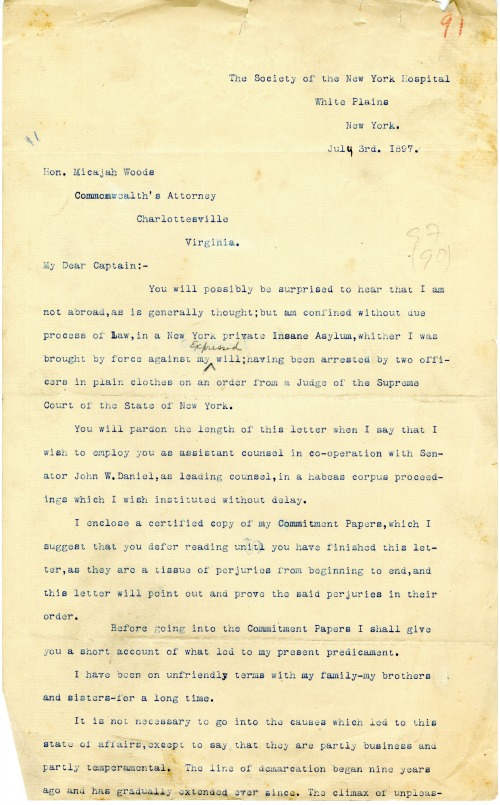

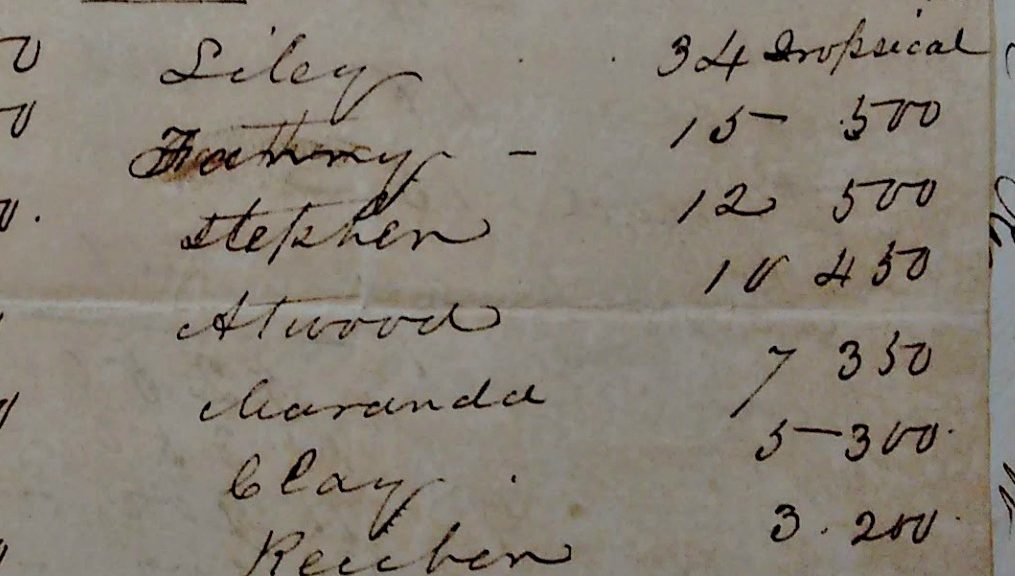

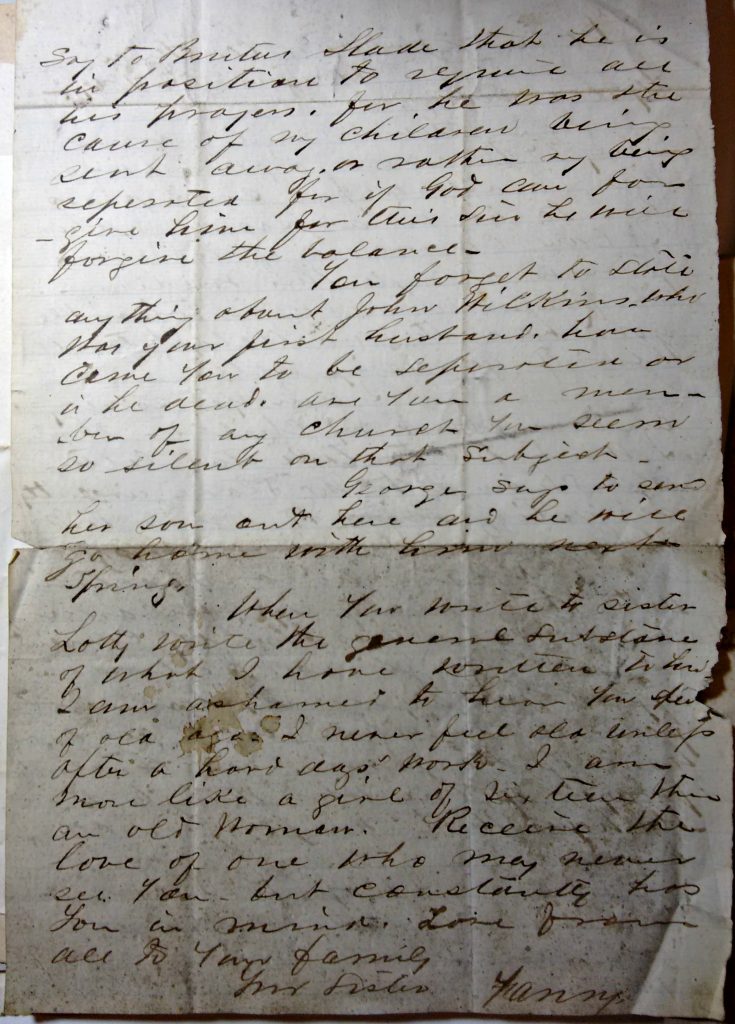

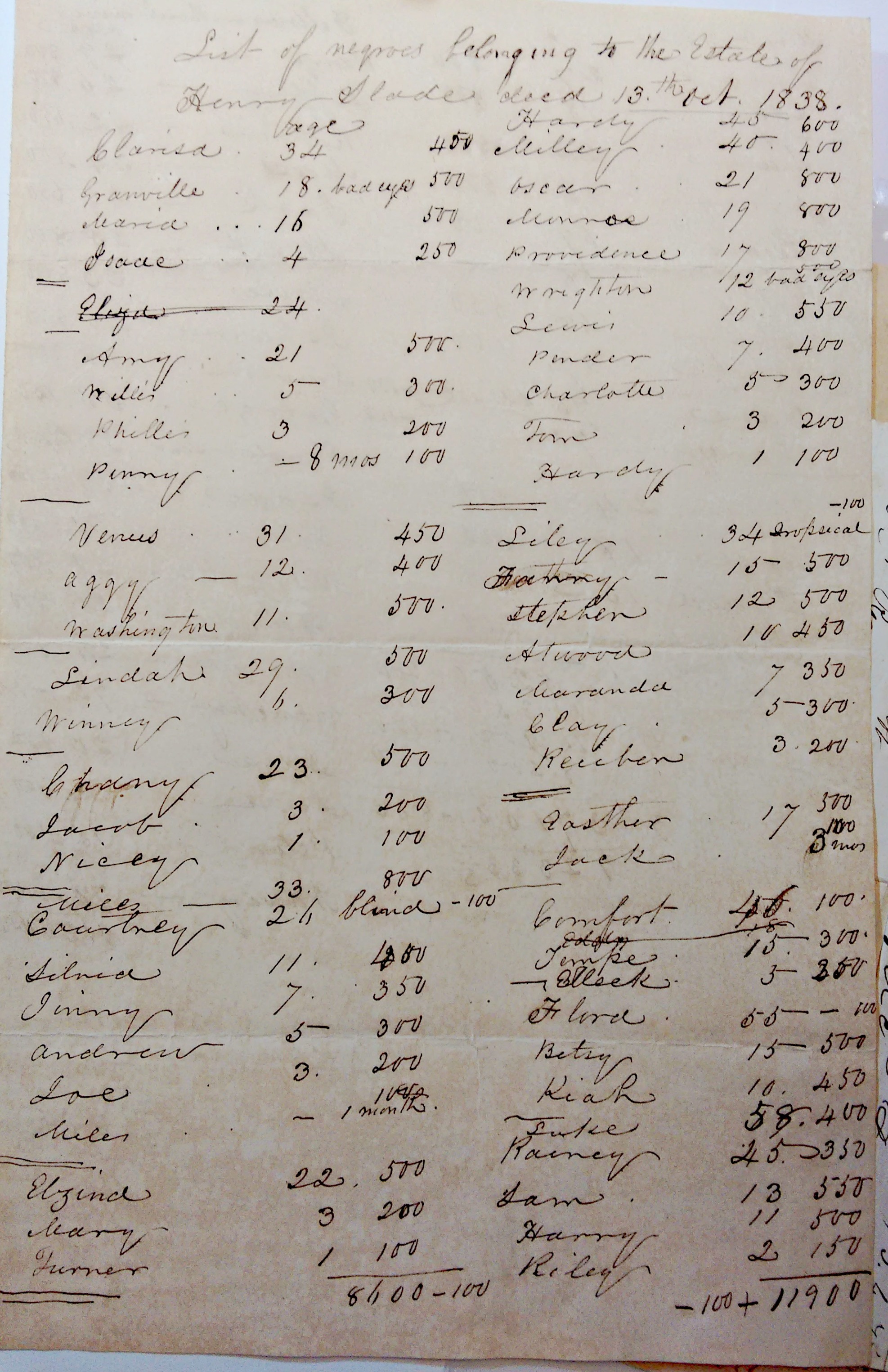

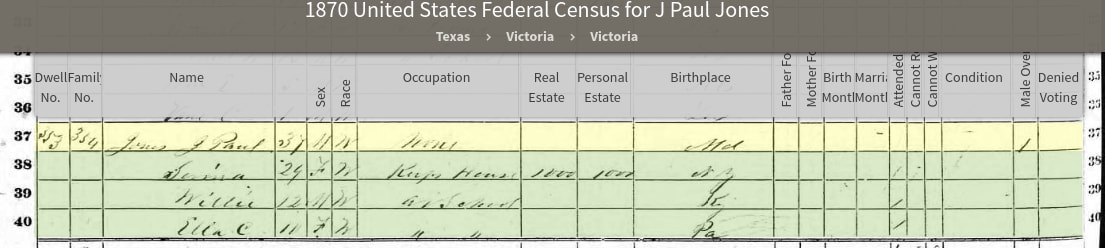

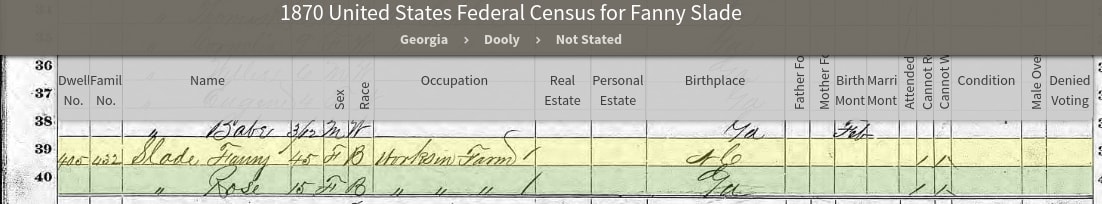

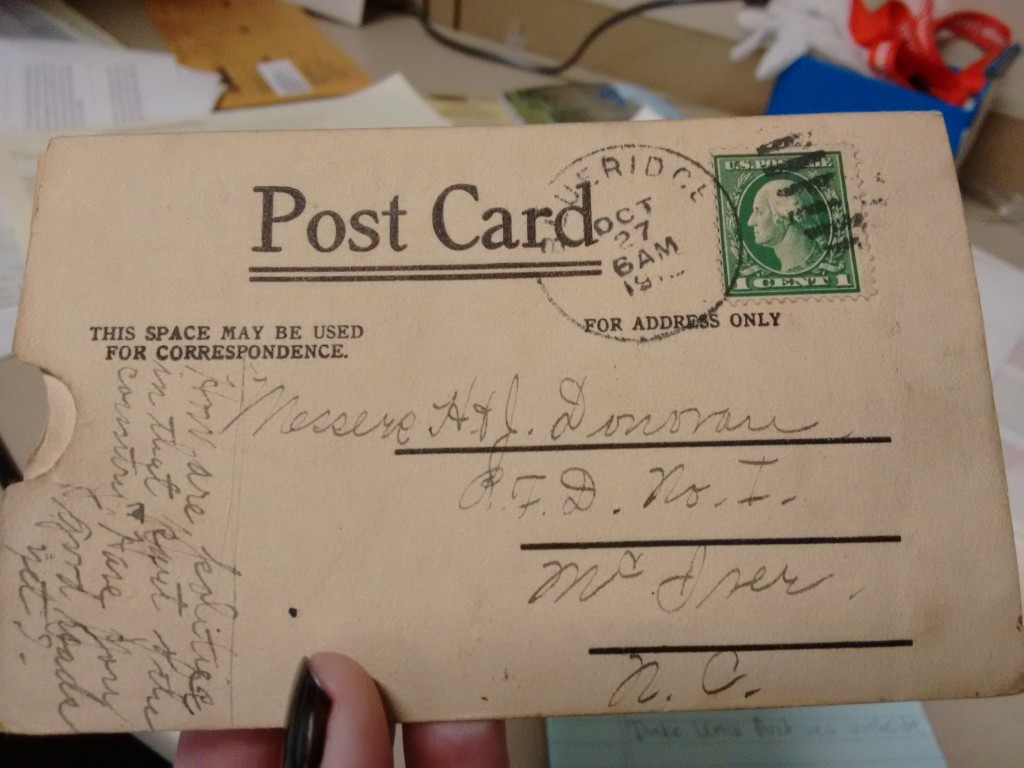

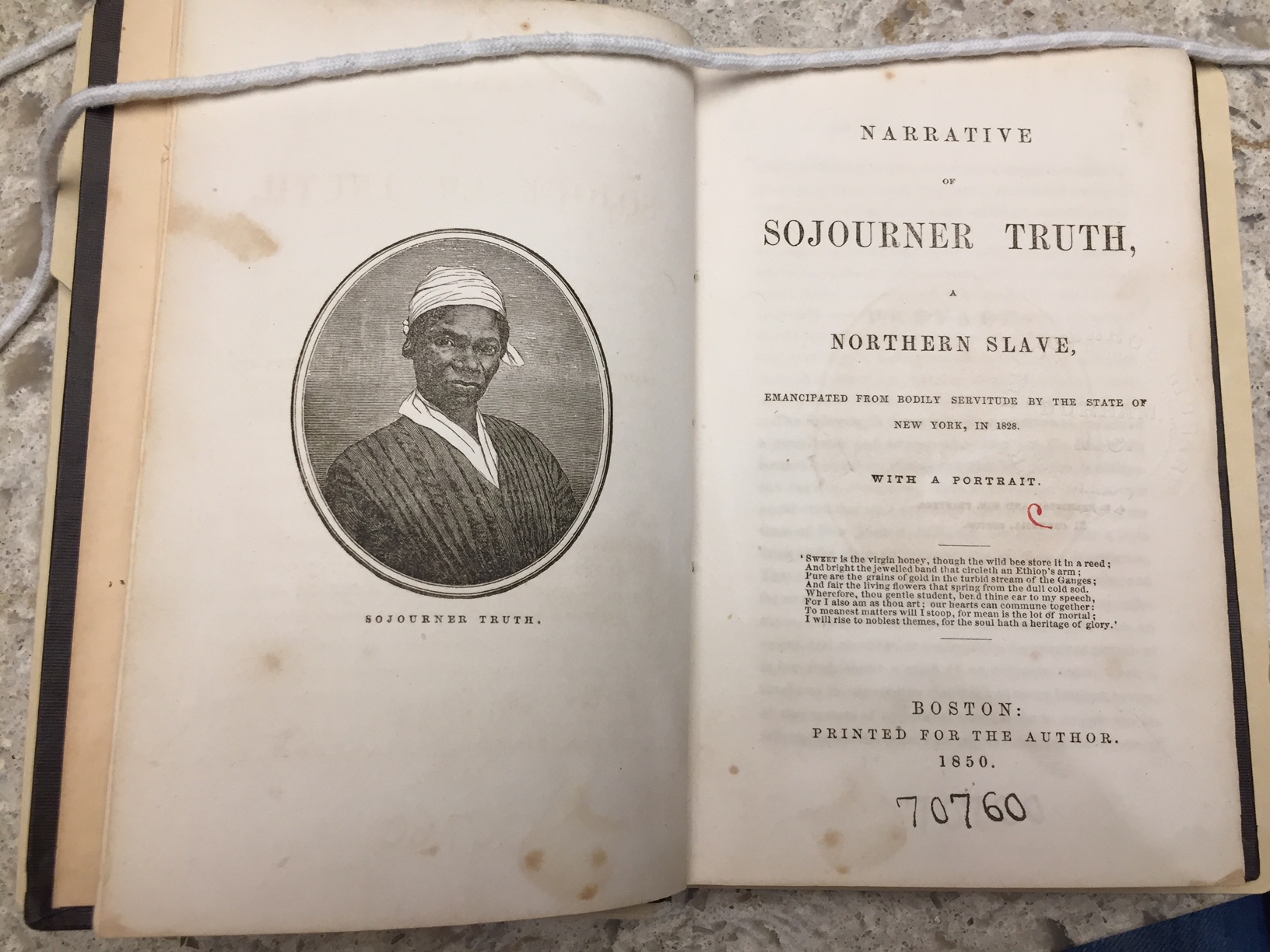

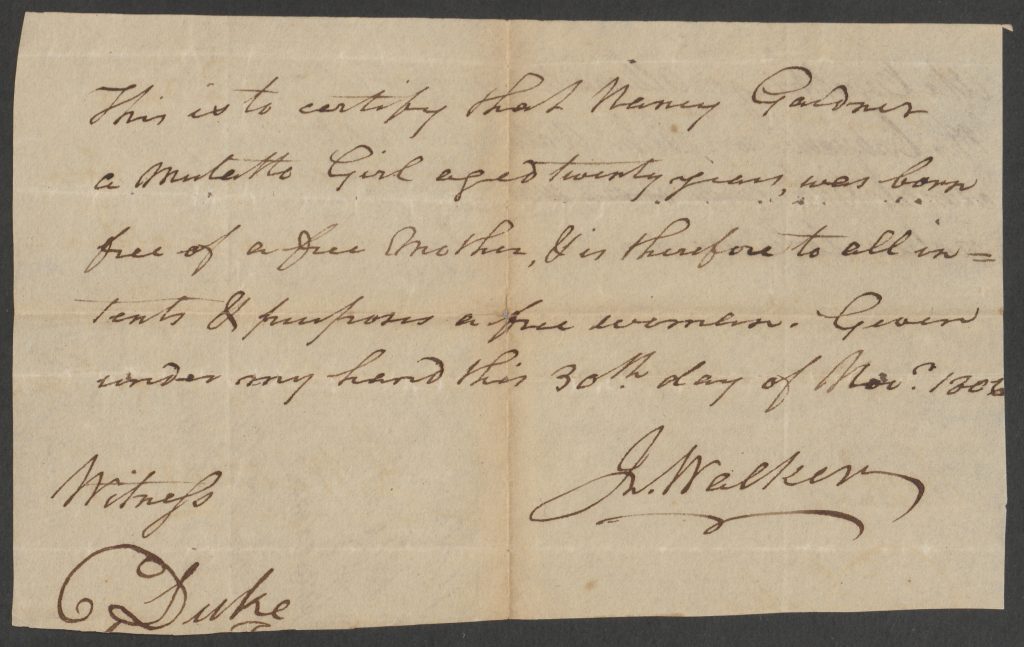

Our projects continue this fall despite the COVID-19 pandemic. While working remotely, the Rare Materials Section has prioritized creating new manuscript catalog records for the Rubenstein’s American Slavery Documents, which will center the names and lives of Black people who were enslaved. We will share more about this project as the records are published in our catalog later this year.

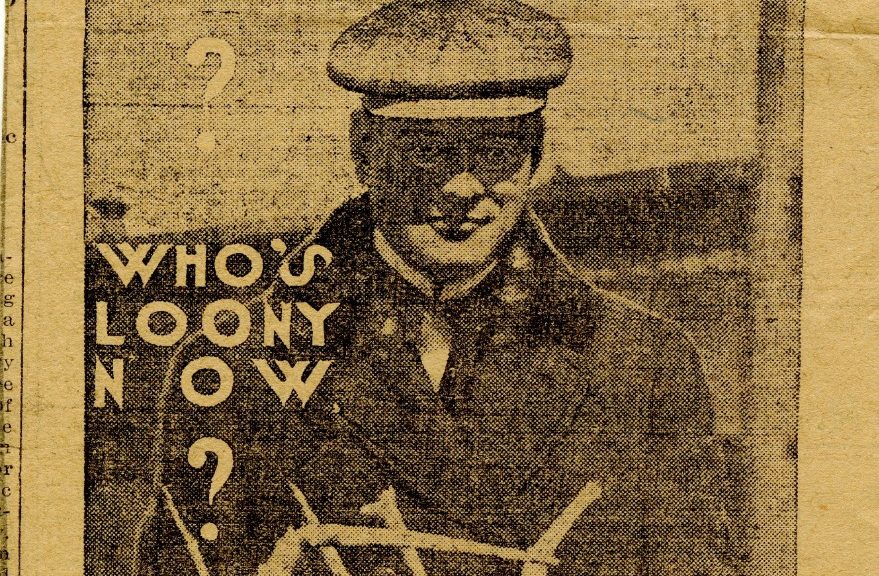

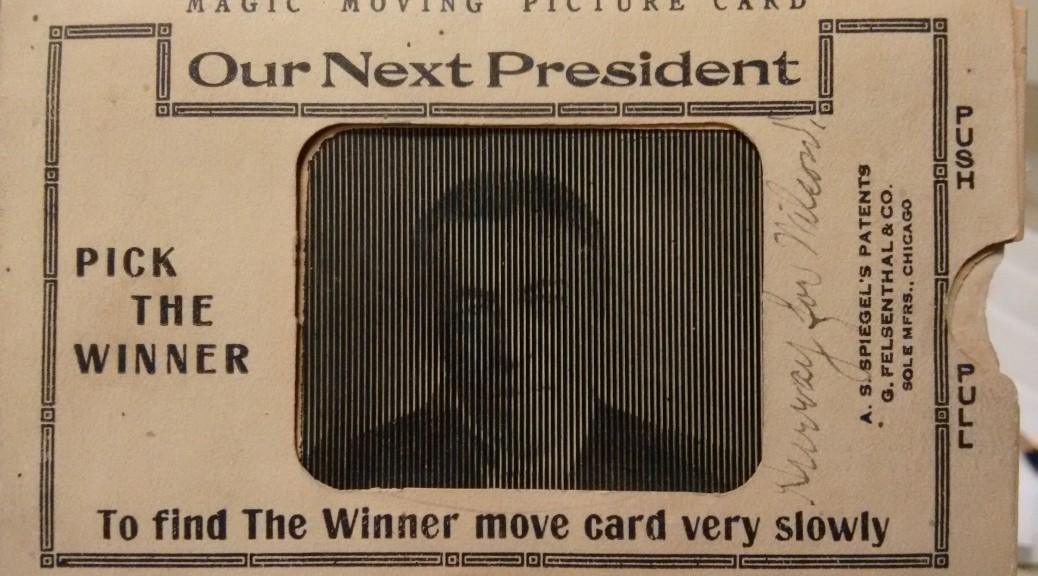

Our Archival Processing Section has begun reviewing manuscript collections with outdated, inadequate, or offensive description, and they will be reprocessing, re-describing, and exploring how to be transparent about any changes or updates they make through development of a new style guide for finding aids. This includes acknowledging our library’s past decisions or mistakes, which may mean more blog posts like this one that question and critique our institution’s collecting and descriptive choices. Across the department, we intend to ramp up reparative description projects, particularly for our nineteenth-century Southern white family papers, because we know that the records of enslavers may be the only remaining documentation of those who were enslaved. We are seeking marginalized, hidden, and silenced voices. Even in their silences, our collections have much to say. Please stay tuned, and stay in touch, as we pursue this important work.