Post contributed by Hannah Ontiveros, Marshall T. Meyer Human Rights Archive Intern

Fall semester 2020 was an odd one, with new challenges, global uncertainty, and everyone stepping out of their comfort zones to find a way to continue learning and working. For me the semester brought unfamiliar work and novel scholarly considerations. As intern for the Human Rights Archive, I spent the semester processing an addition to the Center for Death Penalty Litigation collection. The CDPL is a Durham-based organization that handles post-conviction appeals for indigent people on Death Row in North Carolina. Their ultimate goal is death penalty abolition. Processing this collection raised productive challenges and questions, creating for me a fresh vantage point from which to consider archival practices and the study of human rights.

The process of rehousing documents, seemingly a simple task of moving papers to a fresh, neatly labeled folder in a fresh, neatly labeled box, comes with unexpected challenges and questions. If the documents weren’t organized and separated into folders to begin with, where do they go now? How do we label folders to be succinct and descriptive for future researchers while reflecting the documents’ original use by the CDPL? What does one do when they come across, as I did, a folder containing one single piece of paper, with nothing on it but letterhead? (I kept the document alone in its folder—some future researcher might come across it and glean meaning that I can’t see.)

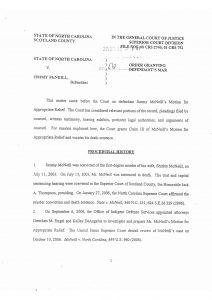

And then there are the photographs. Photographs need to be placed in protective Mylar coverings. This preserves the paper and ink and protects the photos from librarians’ and researchers’ hands when handling them. Again, a seemingly standard task with unexpected challenges. In the CDPL collection, the Human Rights Archives house the organization’s case files, which are expansive. CDPL keeps records from clients’ entire legal history, including their original trial and subsequent appeals, even those not argued by CDPL attorneys. The case files for George Goode, for example, include discovery from his original trial, including crime scene photos. This raised two problems: how do I process these photographs while watching out for my own mental well-being, and how do I describe these photographs for future researchers?

Some of the crime scene photos in the Goode subseries and in others (most notably, David Junior Brown) contain really graphic imagery, including substantial gore. It was very difficult to place the photos in Mylar protectors and rehouse them without looking at them. But I determined that, for the sake of my mental health I couldn’t look at them too much. So I devised for myself a simple and makeshift system of keeping photos faced away from me as much as possible, and keeping them covered with a piece of scrap paper. Having needed to glance at these images in order to process them, I knew the collection required careful description so researchers won’t come across these images without proper warning and preparation.

This raised questions for me of how to describe files with sensitive information in them. We need content warnings that adequately prepare people for the content they’re about to see, but that don’t editorialize too much. Personally, I would describe some of the crime scene photos in this collection as “horrifying,” but that may not be particularly helpful to researchers. Moreover, such description may color researchers’ understanding of the case in a way that’s not productive to grasping the legal stakes at play. With advice from Tracy Jackson in the Rubenstein Library’s Technical Services Department, I opted for describing the images as graphic, and containing gore and deceased persons—at the very least, researchers will know what’s in these folders before opening them. I also opted to place the content warnings in the file and box description in the collection guide, as well as on the physical folder. My hope is that no researcher comes across the photos unaware. It is important that these images, along with the other documents in the collection, are preserved and available for use for productive research on the death penalty and human rights. But it’s also important that researchers are prepared so that their work isn’t hindered by coming across shocking imagery in the archive.

This processing project was also surprising to me on an intellectual level. The study of human rights is important to my own work. But the driving questions about human rights in my dissertation surround issues of global responsibility for refugees, citizenship, and discourses of deservingness. Prior to processing CDPL documents, I had not given much scholarly thought to death penalty abolition, or to criminal litigation as a method for human rights goals. But this processing project made me think about these things. It made me think about how human rights goals are strived for in criminal courts, and the boundaries and possibilities of the law as an avenue for human rights. Through CDPL documents I could see how attorneys understand their clients as whole and deserving people. I can also see how they utilize legal strategies to make whatever gains they can toward their overarching goal of stopping all executions. This is the value of this internship—it broadens my theoretical and methodological understanding of human rights as a field; and it challenges me to think outside of my existing scholarly and political human rights commitments. Ultimately this will make me a better scholar, with a greater appreciation for how documents are created and preserved, and with a more expansive understanding of the field of human rights.

This processing project was also surprising to me on an intellectual level. The study of human rights is important to my own work. But the driving questions about human rights in my dissertation surround issues of global responsibility for refugees, citizenship, and discourses of deservingness. Prior to processing CDPL documents, I had not given much scholarly thought to death penalty abolition, or to criminal litigation as a method for human rights goals. But this processing project made me think about these things. It made me think about how human rights goals are strived for in criminal courts, and the boundaries and possibilities of the law as an avenue for human rights. Through CDPL documents I could see how attorneys understand their clients as whole and deserving people. I can also see how they utilize legal strategies to make whatever gains they can toward their overarching goal of stopping all executions. This is the value of this internship—it broadens my theoretical and methodological understanding of human rights as a field; and it challenges me to think outside of my existing scholarly and political human rights commitments. Ultimately this will make me a better scholar, with a greater appreciation for how documents are created and preserved, and with a more expansive understanding of the field of human rights.

If you’re a bit (or very) obsessed with GBBO and your Valentine loves sweets but isn’t into chocolate, this one’s for you!

If you’re a bit (or very) obsessed with GBBO and your Valentine loves sweets but isn’t into chocolate, this one’s for you!

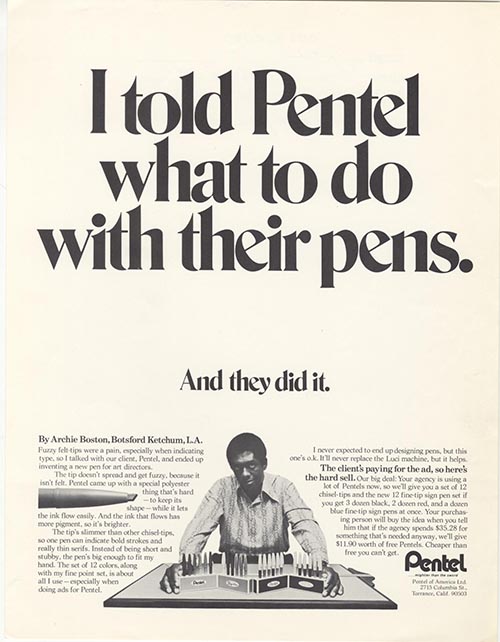

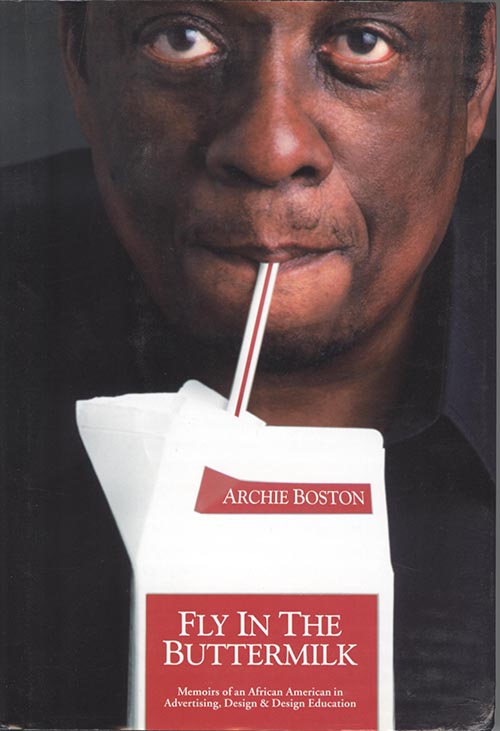

Boston later worked at the ad agency Botsford & Ketchum where he developed one of his most famous ads for Pentel that boasted the caption, “I told Pentel what to do with their pens.” By placing himself at the center of the ad, Boston subverted the usually invisible presence of the advertising executive. At a time when very few African-Americans worked in advertising, the ad also announced a subtle shift in the demographics of the industry.

Boston later worked at the ad agency Botsford & Ketchum where he developed one of his most famous ads for Pentel that boasted the caption, “I told Pentel what to do with their pens.” By placing himself at the center of the ad, Boston subverted the usually invisible presence of the advertising executive. At a time when very few African-Americans worked in advertising, the ad also announced a subtle shift in the demographics of the industry.

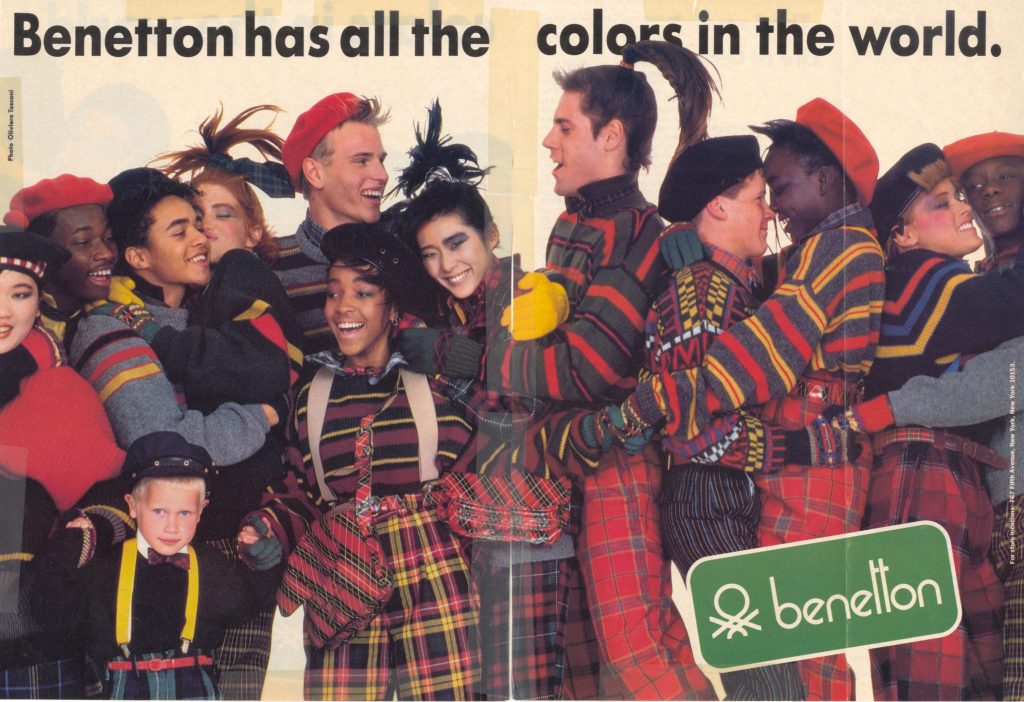

While still invoking the theme of inclusivity, the ad signaled a change in Benetton’s marketing aesthetic. In the 1990s, Benetton ads seemed to be more focused on shock value than clothing. Many of their most controversial images featured no Benetton clothing. Instead, they depicted a wide range of social and political phenomena, from soldiers in the Bosnian war, to a baby with its umbilical cord attached, to a nun and a priest kissing, to a dying AIDS activist. These advertisements were often met with backlash, calls for a boycott of Benetton goods, and, at times, with censorship. Toscani justified these ads in an

While still invoking the theme of inclusivity, the ad signaled a change in Benetton’s marketing aesthetic. In the 1990s, Benetton ads seemed to be more focused on shock value than clothing. Many of their most controversial images featured no Benetton clothing. Instead, they depicted a wide range of social and political phenomena, from soldiers in the Bosnian war, to a baby with its umbilical cord attached, to a nun and a priest kissing, to a dying AIDS activist. These advertisements were often met with backlash, calls for a boycott of Benetton goods, and, at times, with censorship. Toscani justified these ads in an