Post contributed by Kasia Stempniak, Graduate Intern, Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising and Marketing History, and Romance Studies PhD student.

Fashion advertising has never shied away from provocative imagery. One of the first clothing brands to consistently court controversy through advertising was the Italian sportswear brand Benetton. A family owned company established in 1965, Benetton became one of the most successful sportswear brands in Europe in the 1980s. That same decade, Benetton decided to enter the United States market and hired J. Walter Thompson (JWT) as their advertising agency to better reach US consumers. JWT would remain with the Italian brand from 1983 to 1992 and the Benetton advertisements in the JWT archives at the Hartman Center offer a unique look into the evolution of advertising conventions in the fashion industry.

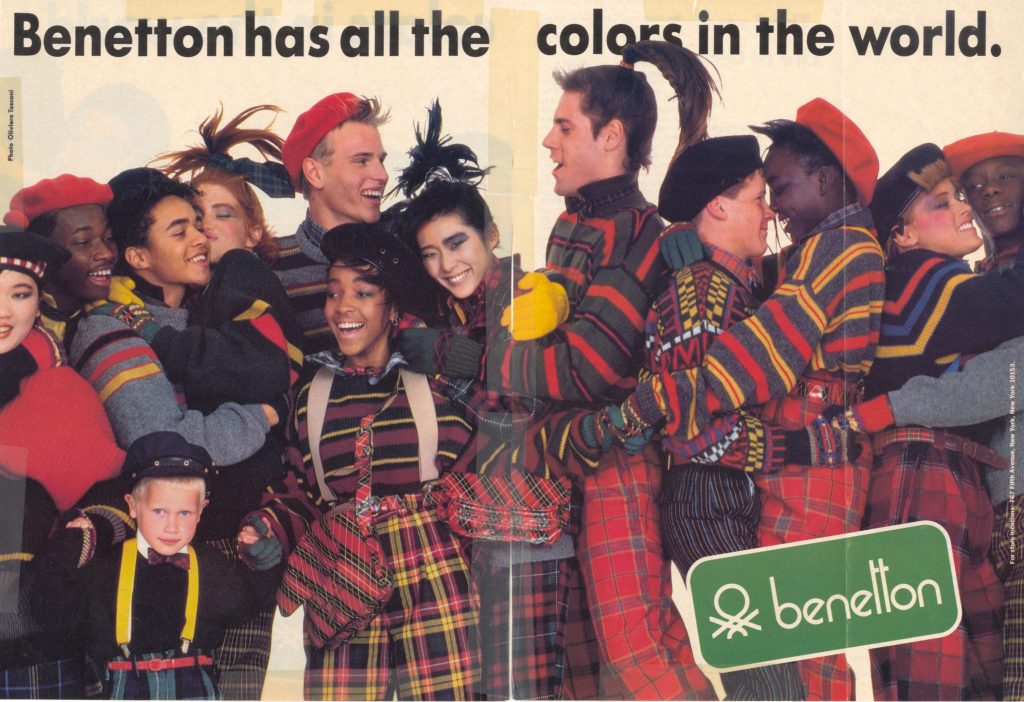

With the Italian photographer Oliviero Toscani as the creator of its advertisements, Benetton launched a series of ads in 1983 that were designed to be explicit celebrations of diversity and inclusivity. These ads, like the one seen above that was featured in the magazine Mademoiselle in 1983, were part of a campaign called “All the Colors of the World.” With their messages of global harmony, these ads would take on dozens of different iterations in the next two decades. They became such a staple in Benetton’s marketing repertoire that in the 1990s, the expression “a Benetton ad” was sometimes used to refer to an image with a diverse group of people. Some of these ads tackled politics, like this advertisement diffused during the Cold War in 1986 that featured two athletes, one from the US and one from the USSR, in a friendly pose.

Roughly a decade after the first “All the Colors of the World” world campaign, Benetton released a modified version of these ads. In lieu of a line of smiling faces, however, the ad featured vials of blood labeled with different first names. While still invoking the theme of inclusivity, the ad signaled a change in Benetton’s marketing aesthetic. In the 1990s, Benetton ads seemed to be more focused on shock value than clothing. Many of their most controversial images featured no Benetton clothing. Instead, they depicted a wide range of social and political phenomena, from soldiers in the Bosnian war, to a baby with its umbilical cord attached, to a nun and a priest kissing, to a dying AIDS activist. These advertisements were often met with backlash, calls for a boycott of Benetton goods, and, at times, with censorship. Toscani justified these ads in an interview with The New York Times in 1991, explaining that he saw advertising as both an artistic and political endeavor: “I have found out that advertising is the richest and most powerful medium existing today, so I feel responsible to do more than to say, ‘Our sweater is pretty.’” JWT and Benetton separated in 1992, but Benetton continues to test the limits of public reception with their advertising, despite experiencing a slip in popularity over the past two decades. As recently as 2018, a Benetton ad elicited vociferous criticism from politicians and consumers in Italy and around the world when it repurposed a photograph of migrants being rescued in the Mediterranean Sea.

While still invoking the theme of inclusivity, the ad signaled a change in Benetton’s marketing aesthetic. In the 1990s, Benetton ads seemed to be more focused on shock value than clothing. Many of their most controversial images featured no Benetton clothing. Instead, they depicted a wide range of social and political phenomena, from soldiers in the Bosnian war, to a baby with its umbilical cord attached, to a nun and a priest kissing, to a dying AIDS activist. These advertisements were often met with backlash, calls for a boycott of Benetton goods, and, at times, with censorship. Toscani justified these ads in an interview with The New York Times in 1991, explaining that he saw advertising as both an artistic and political endeavor: “I have found out that advertising is the richest and most powerful medium existing today, so I feel responsible to do more than to say, ‘Our sweater is pretty.’” JWT and Benetton separated in 1992, but Benetton continues to test the limits of public reception with their advertising, despite experiencing a slip in popularity over the past two decades. As recently as 2018, a Benetton ad elicited vociferous criticism from politicians and consumers in Italy and around the world when it repurposed a photograph of migrants being rescued in the Mediterranean Sea.

The Benetton ads in the JWT archive shed light on how a fashion company adopted unconventional methods of advertising as a way to connect with a younger generation and bring awareness to social issues. At the same time, reactions to these ads indicate that consumers were uneasy with the confluence of fashion and social commentary. Today, clothing companies are increasingly placing social causes at the center of their ads, like British clothing chain Jigsaw and their 2017 “Love Immigration” campaign. Did Benetton’s advertisements pioneer this modern phenomenon of “brand activism”? Or were Benetton’s ads an example of a company commodifying social causes and taking advantage of the ethically murky waters of fashion advertising?