Post contributed by Tracy Jackson, Head, Center Manuscript Processing Section and Technical Services Archivist for the Duke University Archives.

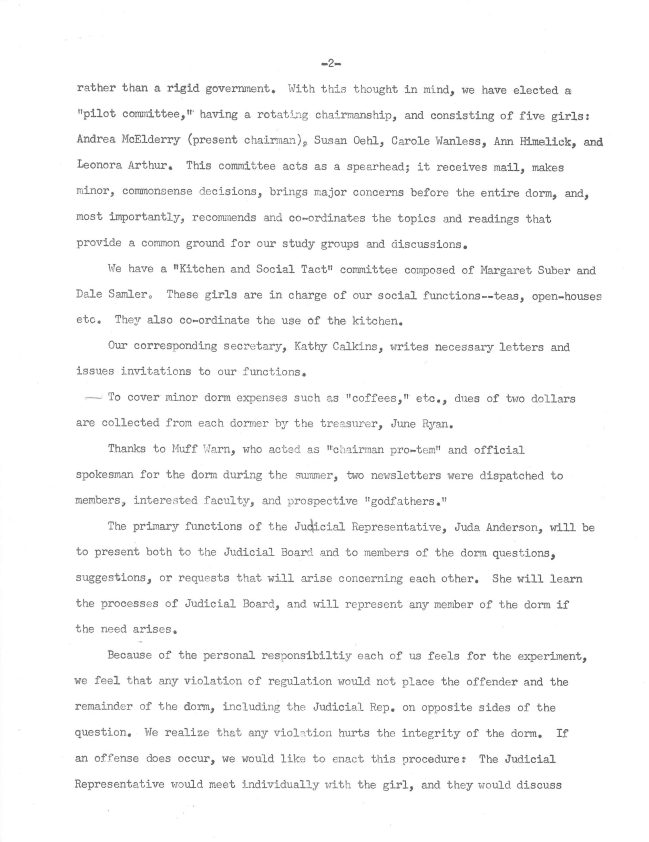

The Women’s Studies Program was founded in 1983, but women have been attending and graduating from Duke since the 1870s, and have been active as alums and supporters of the University. In the mid and late 1980s, as the Women’s Studies Program (WSP) was growing rapidly, they began to form a Friends of Women’s Studies group to help support the growth and evolution of the academic program.

In 1987, administrators in WSP created a survey focused on women’s experiences and sent it to the more than 16,000 women who had received undergraduate degrees from Duke since the 1920s. More than 700 responses came back. The first issue of the Women’s Studies Program Friends Newsletter published summary results of the survey in Spring of 1988. The piece in the newsletter breaks down the percentage of responses by decade of graduation, gives an overview of advanced degrees received and professions pursued, and includes information about involvement with alumni organizations, a major concern to WSP at the time. The following two issues of the Friends Newsletter give more in-depth profiles of the two women most commonly cited as role models by the survey respondents, Anne Scott and Juanita Kreps.

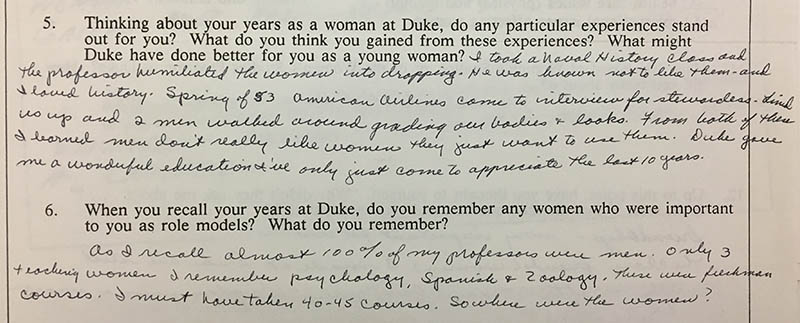

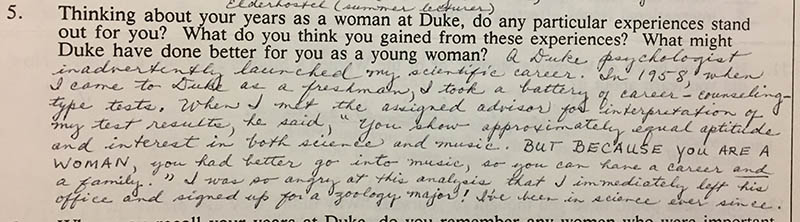

The survey asks about a number of issues not covered in the Newsletter summary, however, and the answers are fascinating. The survey includes questions about what women experienced as women at Duke, about what they would want to discuss with then-current students, about what they saw as the most important events for women in the last 25 years, whether they’d ever heard of Women’s Studies, and what else they should have been asked.

The answers to these questions give us a glimpse of what women’s lives were like at Duke over the decades, but they also show what the respondents saw as mattering to women’s lives at the time. It’s important to realize the limitations of this trove of information: since Duke didn’t desegregate until 1965, this is what predominantly white, relatively affluent women thought in 1987 and 1988. From the perspective of 2019, 30 years later, it is very much of the moment of the late 1980s, yet has strong echoes of concerns women still struggle with now.

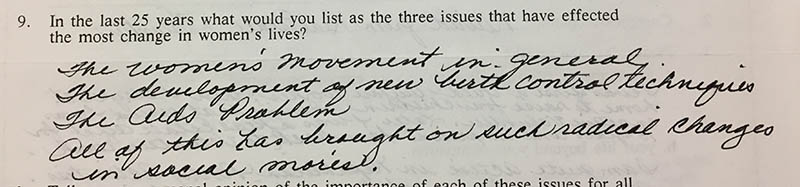

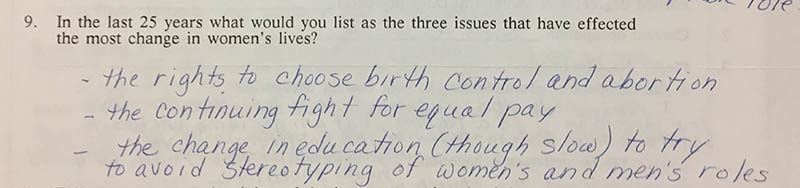

The responses on what were the most important issues to women in the last 25 years had a few common themes most often listed: birth control, both contraceptives as in the pill, and legalized abortion after Roe v. Wade, grouped together as well as listed separately; greater number of women in the workplace, sometimes listed in conjunction with concerns about equal pay, sometimes with concerns about the economic necessity of married women working (with some respondents questioning the necessity), and often in conjunction with concerns about the effect of working mothers on “the family”; civil rights; and greater visibility of women’s efforts to achieve equality, as in the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), the women’s movement and feminism, and wondering if women can really have it all. Other concerns often listed include AIDS, drugs, and welfare, issues that would have been frequently and prominently discussed in the late 1980s. In my random sampling I didn’t find any mention of lesbian or queer issues, or of immigration or refugee concerns, and very little mention of the specific needs of women of color. But the focus on issues of equality, economic concerns, reproductive justice, and whether women can really get what they need in a complicated world – these all still ring so true for me today.

(Editor’s note: the text of these responses should be accessible as alt text via your screen reader. Please let us know if that’s not the case!)

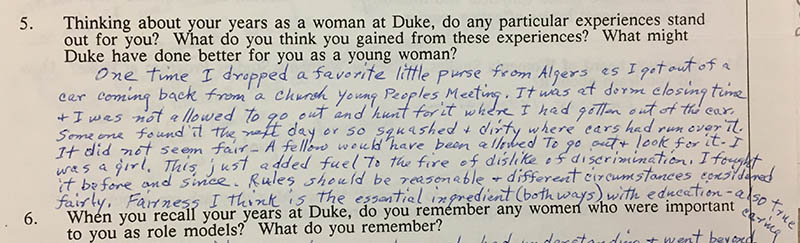

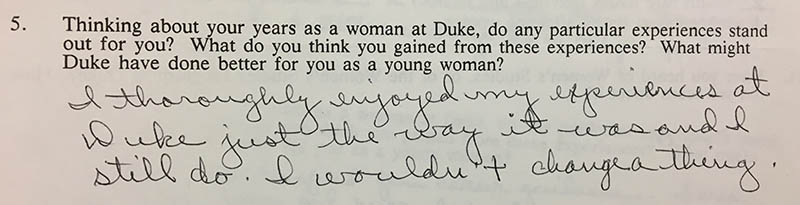

The long answers are my favorite, especially about the respondents’ memories of Duke. They’re anecdotal and can’t necessarily be used to draw larger conclusions, but in my brief review some patterns did emerge: there weren’t enough women faculty; everyone wanted more counselling, whether for future careers or life during and after college or handling alcohol; most people struggle to “have it all” and it’s important to address that.

Most of the memories of time at Duke are pleasant, recalling friendships still important in the lives of these women. There are, however, a number of vivid anecdotes of facing sexism from the administration or predominantly male faculty or from the career world outside of Duke. There are also reminisces of struggling to fit in, and struggling to find one’s place in the world or find appropriate role models. These, I think, are concerns still relevant today, even as we have far greater numbers of women in faculty and mentorship roles.

![Question 5: “Thinking about your years as a woman at Duke, do any particular experiences stand out for you? What do you think you gained from these experiences? What might Duke have done better for you as a young woman?” Answer: “I was lucky to have lived in Epworth for two years where many strong-willed, energetic, creative women students served as role models and challenged me. (I was VP one semester and Pres. another.) They gave me courage. I dropped my math major my sophomore year – was told by my math prof. (a young-ish male – [name redacted]) that women usually don’t make it as mathematicians because they are not aggressive enough. By the end of my soph. year, there was only one other woman besides myself in my math class. I get angry every time I think about the chilling effect this prof. had on my – I sincerely hope that he’s no longer teaching at Duke.”](http://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2019/06/1977_Q5_1.jpg)