Post contributed by Sarah Bernstein, Josiah Charles Trent History of Medicine Intern.

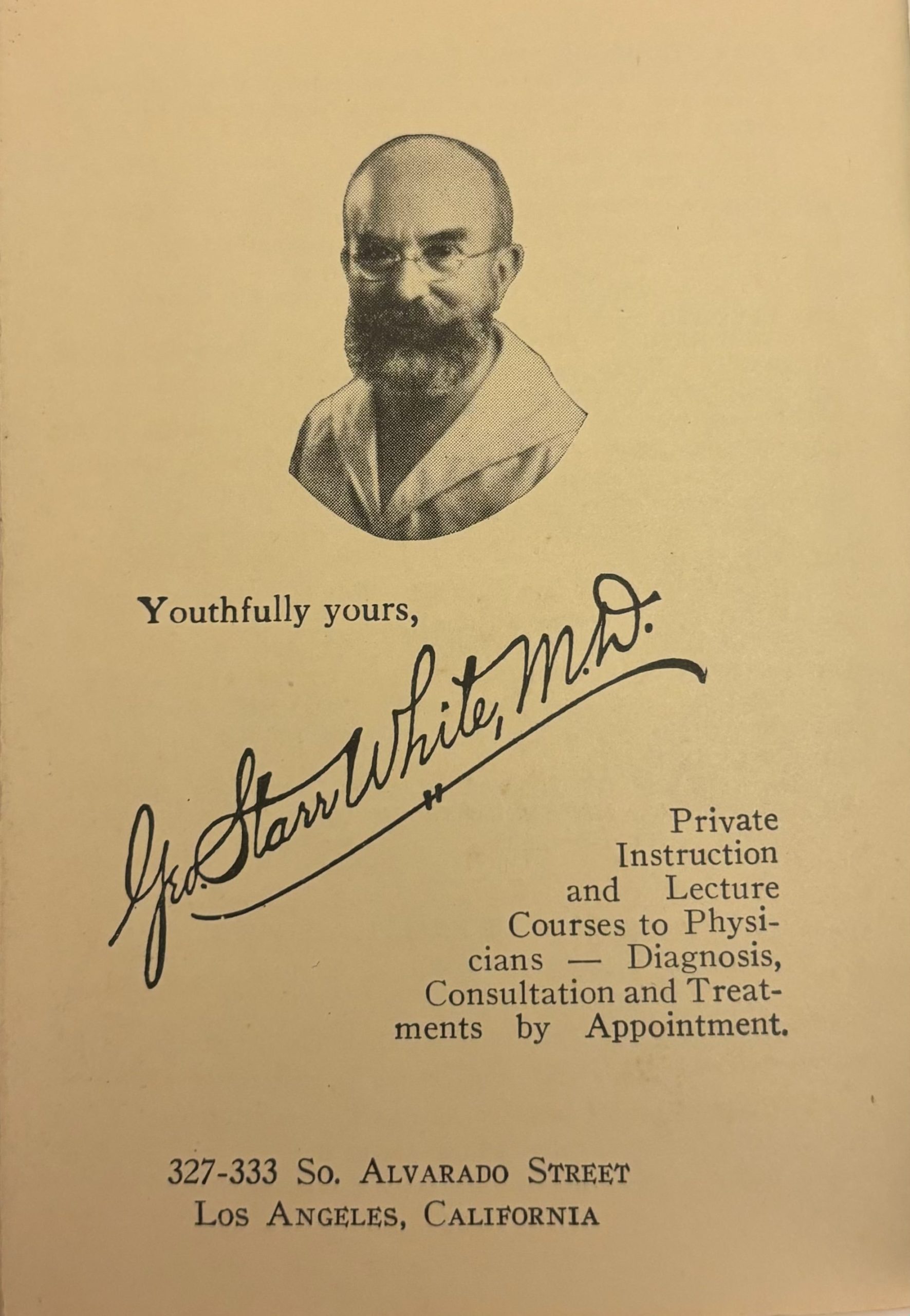

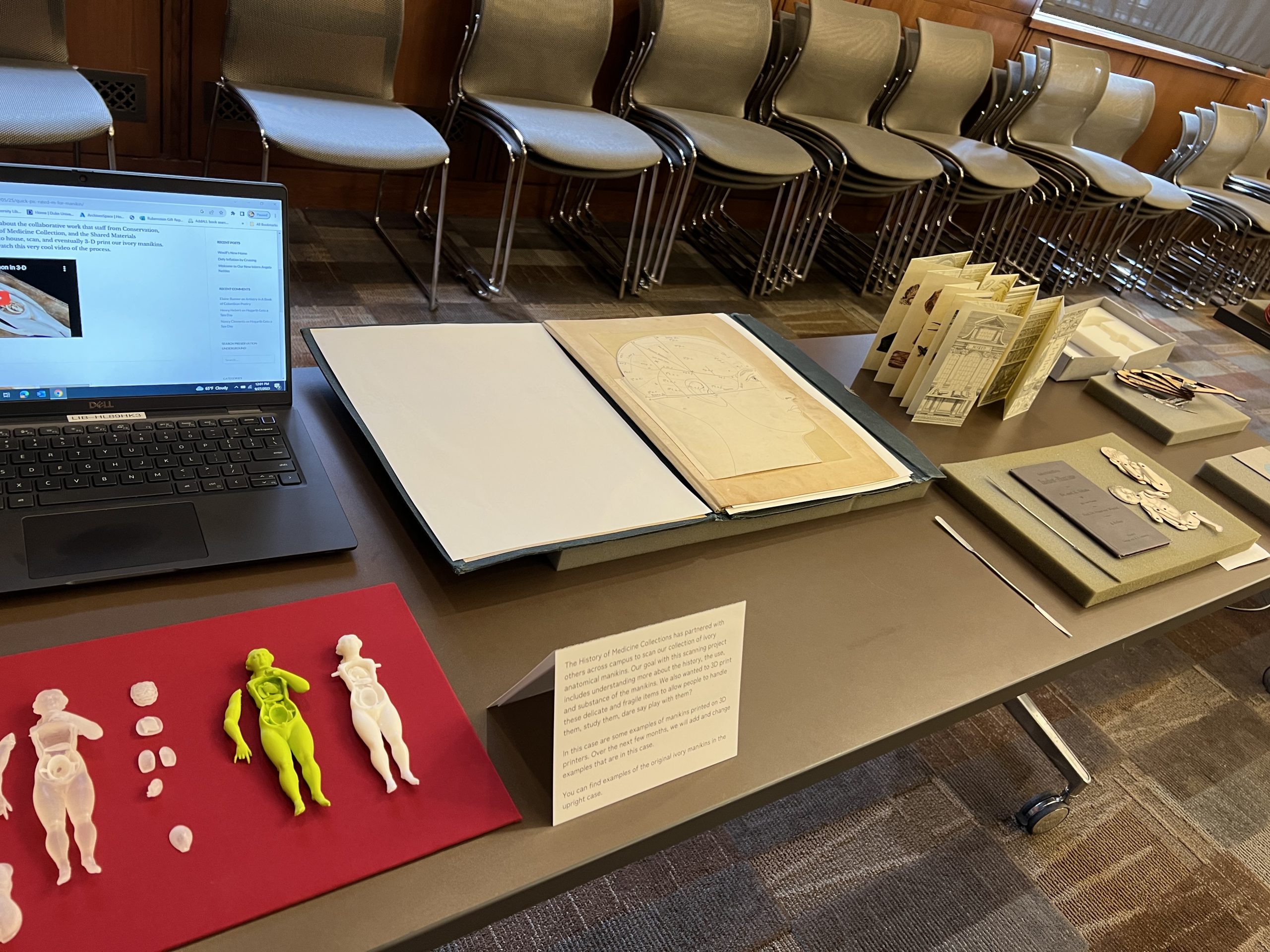

As someone who studies unorthodox and fringe medicine, I was incredibly pleased to find the large arrangement of unorthodox, fringe, strange, and frankly “quack” medicine within the Rubenstein Library. While the rich History of Medicine Collections includes classics of Western medicine like a first edition of Andreas Vesalius’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica, a memento mori in carved ivory, and various microscopes (on permanent display in the Trent Room), I am glad to share that there are also patent medicine bottles, advertisements, and numerous writings and publications on alternative and unorthodox medicine. George Starr White’s My Little Library of Health is one such series of advice from a so-called “quack,” or an illegitimate and opportunistic, doctor.

The 1928 “little library” by White is a series of 28 books whose length ranges from 20–48 pages. While small, I would say that calling them “thumb-nail” editions is a little misleading; the books measure at 4.5 inches in height and near 3.5 inches across (3 ⁷⁄₁₆ to be exact) is far from what is considered a miniature book or thumbnail sized. The advertisement at the back for each book boasted that each book contained illustrations, sometimes in color, and provided White’s sound advice on “health building by natural living.” Each book could be purchased for 25 cents (now somewhere near $4.50) or, for 5 dollars prepaid (around $90 for us today), one could score for the entire set.

The 1928 “little library” by White is a series of 28 books whose length ranges from 20–48 pages. While small, I would say that calling them “thumb-nail” editions is a little misleading; the books measure at 4.5 inches in height and near 3.5 inches across (3 ⁷⁄₁₆ to be exact) is far from what is considered a miniature book or thumbnail sized. The advertisement at the back for each book boasted that each book contained illustrations, sometimes in color, and provided White’s sound advice on “health building by natural living.” Each book could be purchased for 25 cents (now somewhere near $4.50) or, for 5 dollars prepaid (around $90 for us today), one could score for the entire set.

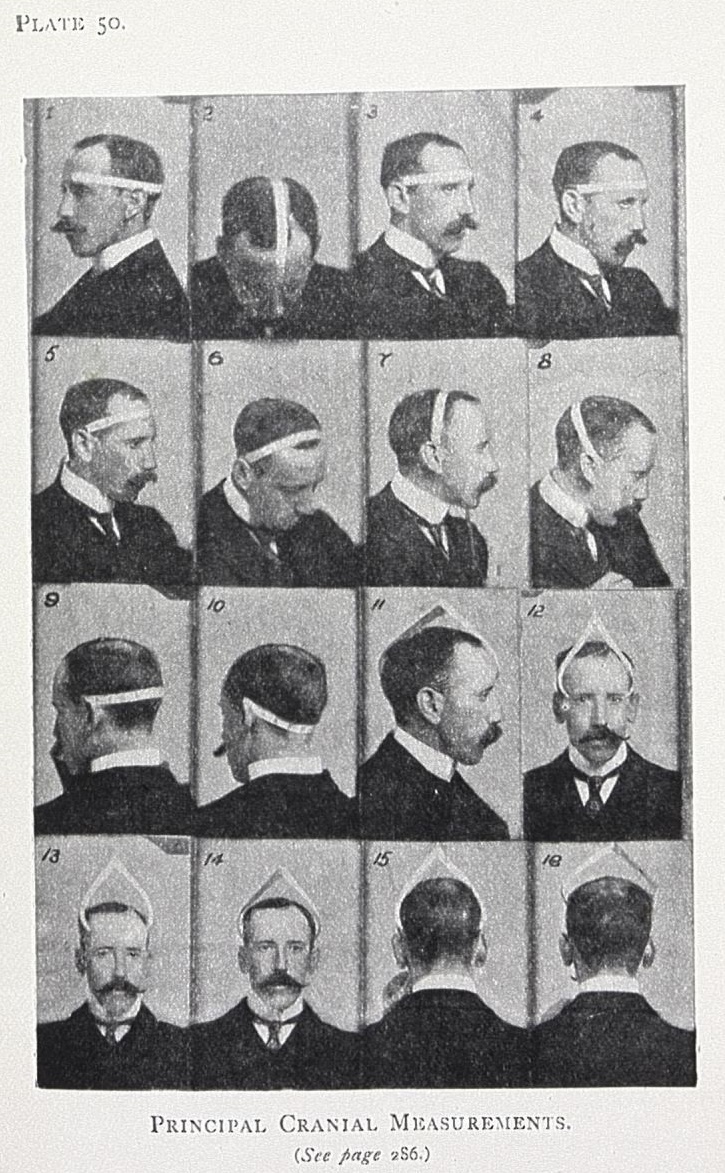

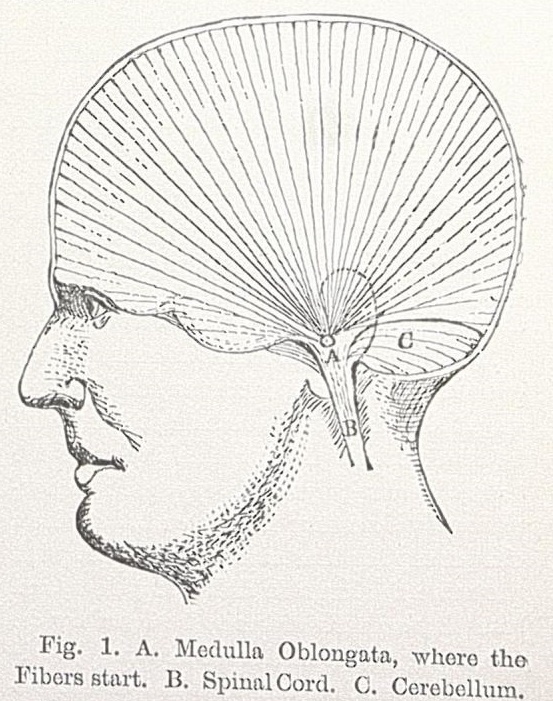

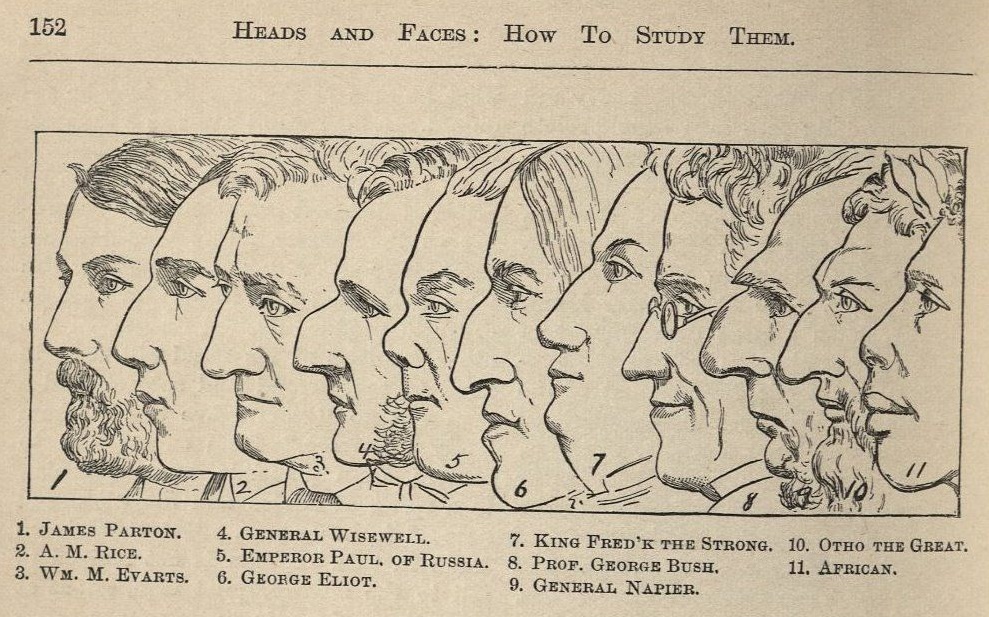

White was a proponent of chromotherapy, light therapy, and heat therapy. In My Little Library of Health he informed his readers about his research and strong belief in the healing properties of Ultra-Red Rays. Although White’s belief in chromotherapy began by viewing sunlight through oak leaves, based on his account in volume 27, his tests had revealed to him that artificial lights from electric lamps still produced healing effects. In fact, some electric lamps worked better than others. Why? Ultra-Red Rays, that White describes as “the ‘thermal’ Rays upon which all life depends,” more commonly known as infrared light. Based on these beliefs, White developed the “Filteray Pad,” a heat pad which generated Ultra-Red Rays and was meant to be applied to the affected area. The price for this cure-all device? A cool $35 (~$620-30 in 2024).

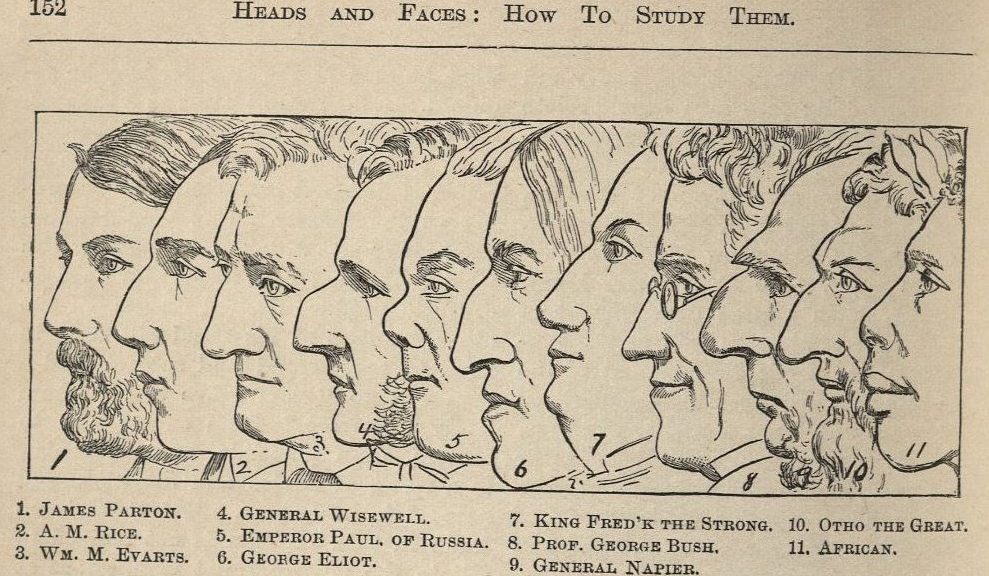

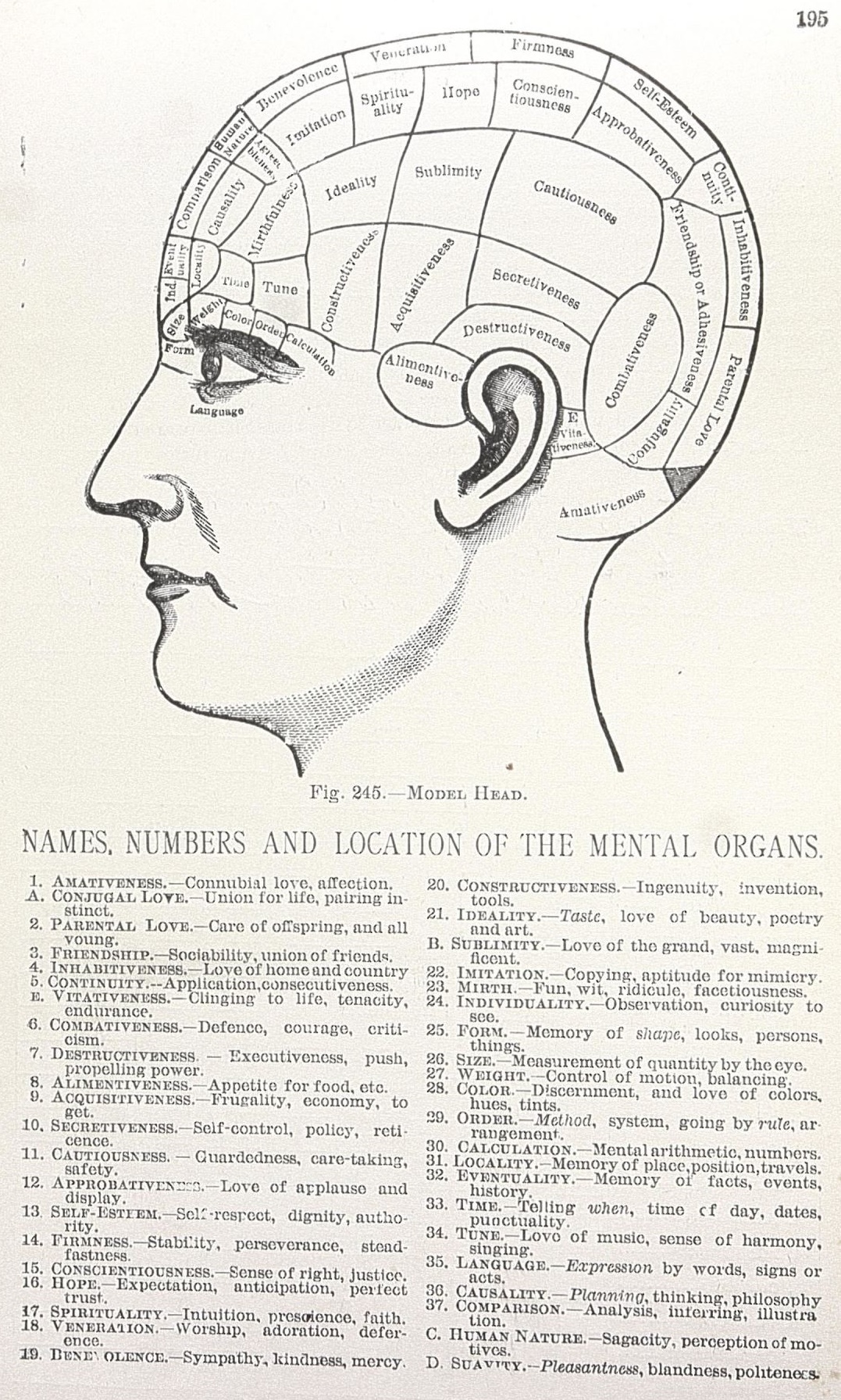

White would go on to develop other light-based therapies and medical systems. In 1929, White was unflatteringly covered in the “Bureau of Investigation” section of The Journal of the American Medical Association (volume 92, number 15) for his dubious claim of medical schooling and his career in patent medicines. The article lambasted White and all of his medicines and cures. Along with the “Filteray Pad” there was “Valens Essential Oil Tablets” (sold during the 1918 Flu Epidemic for “Gripping the Flu out of Influenza”) and his methods of “Bio-Dynamic-Chromatic (B-D-C) Diagnosis” and “Ritho-Chrome Therapy” (light-based diagnosis and cure using multiple colored rays that were similar to other forms of chromotherapy; the “Electronic Reactions of Abrams” by Albert Abrams and Dinshah Ghadiali’s “Spectro-Chrome” device respectively).

The Bureau of Investigation (formerly the Propaganda for Reform Department) was created as an outgrowth from the Council on Chemistry and Pharmacy to specifically investigate, disprove, and inform the public about fraudulent nostrums and patent medicine. The effort was headed by Dr. Arthur J. Cramp, a passionate doctor who was highly critical of nostrums, patent medicines, and the lax regulations which enabled proprietors to label and advertise their products as legitimate medicines.

George Starr White was just one of many quacks that Dr. Cramp and The Journal of the American Medical Association investigated and denounced, and who are represented in the Rubenstein Library’s collections. While I would not advise anyone to turn to White for medical advice today, I would encourage people to think about illegitimate medical professionals like White—and the world that they operated in—in contrast to medicine and the medical system today. These quacks from the past can provide insight into how medicine is legitimized, the rise of the medical profession, and continuous efforts throughout history to seek and provide unorthodox care.