Photo Credit: NYT

Blog post written by Lindsey Allison, a current graduate student at the School of Information and Library Science at UNC-Chapel Hill.

On the prowl for your next great read? The New York Times has the list for you! Curated by a mix of writers, readers, and staff, this list takes a long look at influential titles published in the 21st century. Check out their top 20 picks below and see here for a glance at all 100.

Is your favorite title absent from the list? No problem! Join writers like Stephen King and Min Jin Lee to submit your own top 10 recommendations.

Whether it’s taking a walk down memory lane or discovering something new, enjoy this celebration of the last 25 years of literature.

20: Erasure by Percival Everett (2001)

Thelonious “Monk” Ellison’s writing career has bottomed out: his latest manuscript has been rejected by seventeen publishers, which stings all the more because his previous novels have been “critically acclaimed.” He seethes on the sidelines of the literary establishment as he watches the meteoric success of We’s Lives in Da Ghetto, a first novel by a woman who once visited “some relatives in Harlem for a couple of days.” Meanwhile, Monk struggles with real family tragedies-his aged mother is fast succumbing to Alzheimer’s, and he still grapples with the reverberations of his father’s suicide seven years before. In his rage and despair, Monk dashes off a novel meant to be an indictment of Juanita Mae Jenkins’s bestseller. He doesn’t intend for My Pafology to be published, let alone taken seriously, but it is-under the pseudonym Stagg R. Leigh-and soon it becomes the Next Big Thing. How Monk deals with the personal and professional fallout galvanizes this audacious, hysterical, and quietly devastating novel.

19: Say Nothing by Patrick Keefe (2019)

Patrick Radden Keefe’s mesmerizing book on the bitter conflict in Northern Ireland and its aftermath uses the McConville case as a starting point for the tale of a society wracked by a violent guerrilla war, a war whose consequences have never been reckoned with. The brutal violence seared not only people like the McConville children, but also I.R.A. members embittered by a peace that fell far short of the goal of a united Ireland, and left them wondering whether the killings they committed were not justified acts of war, but simple murders. From radical and impetuous I.R.A. terrorists such as Dolours Price, who, when she was barely out of her teens, was already planting bombs in London and targeting informers for execution, to the ferocious I.R.A. mastermind known as The Dark, to the spy games and dirty schemes of the British Army, to Gerry Adams, who negotiated the peace but betrayed his hardcore comrades by denying his I.R.A. past—Say Nothing conjures a world of passion, betrayal, vengeance, and anguish.

18: Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders (2017)

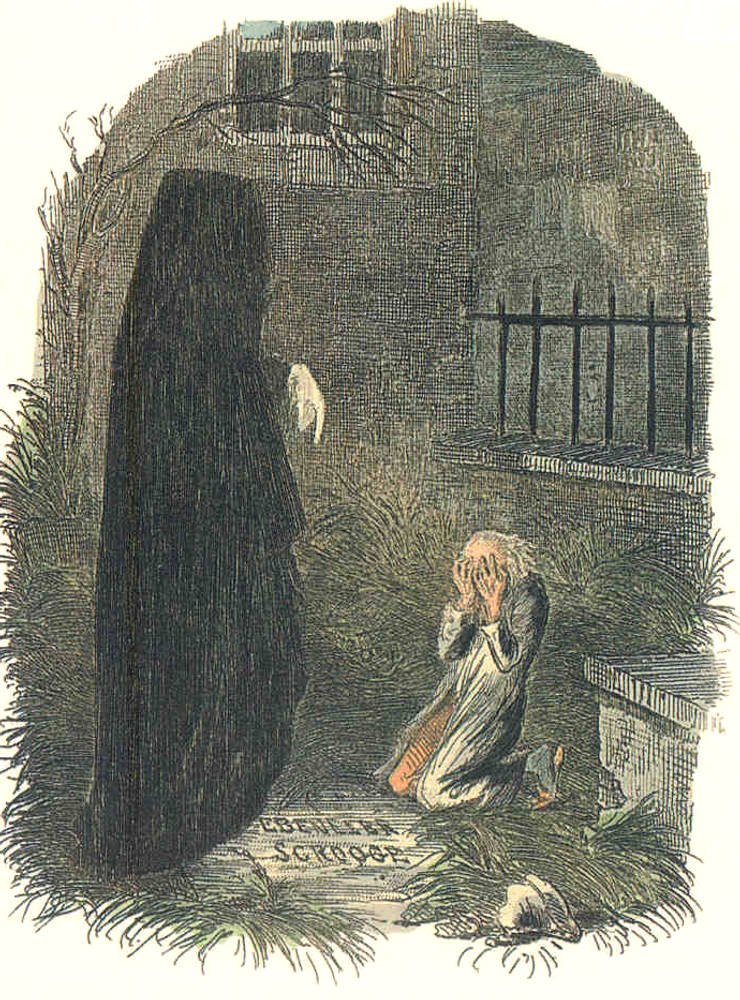

February 1862. The Civil War is less than one year old. The fighting has begun in earnest, and the nation has begun to realize it is in for a long, bloody struggle. Meanwhile, President Lincoln’s beloved eleven-year-old son, Willie, lies upstairs in the White House, gravely ill. In a matter of days, despite predictions of a recovery, Willie dies and is laid to rest in a Georgetown cemetery. “My poor boy, he was too good for this earth,” the president says at the time. “God has called him home.” Newspapers report that a grief-stricken Lincoln returns, alone, to the crypt several times to hold his boy’s body. From that seed of historical truth, George Saunders spins an unforgettable story of familial love and loss that breaks free of its realistic, historical framework into a supernatural realm both hilarious and terrifying. Willie Lincoln finds himself in a strange purgatory where ghosts mingle, gripe, commiserate, quarrel, and enact bizarre acts of penance. Within this transitional state—called, in the Tibetan tradition, the bardo—a monumental struggle erupts over young Willie’s soul.

17: The Sellout by Paul Beatty (2015)

Born in the “agrarian ghetto” of Dickens—on the southern outskirts of Los Angeles—the narrator of The Sellout resigns himself to the fate of lower-middle-class Californians: “I’d die in the same bedroom I’d grown up in, looking up at the cracks in the stucco ceiling that’ve been there since ’68 quake.” Raised by a single father, a controversial sociologist, he spent his childhood as the subject in racially charged psychological studies. He is led to believe that his father’s pioneering work will result in a memoir that will solve his family’s financial woes. But when his father is killed in a police shoot-out, he realizes there never was a memoir. All that’s left is the bill for a drive-thru funeral. Fuelled by this deceit and the general disrepair of his hometown, the narrator sets out to right another wrong: Dickens has literally been removed from the map to save California from further embarrassment. Enlisting the help of the town’s most famous resident—the last surviving Little Rascal, Hominy Jenkins—he initiates the most outrageous action conceivable: reinstating slavery and segregating the local high school, which lands him in the Supreme Court.

16: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon (2000)

A young escape artist and budding magician named Joe Kavalier arrives on the doorstep of his cousin, Sammy Clay. While the long shadow of Hitler falls across Europe, America is happily in thrall to the Golden Age of comic books, and in a distant corner of Brooklyn, Sammy is looking for a way to cash in on the craze. He finds the ideal partner in the aloof, artistically gifted Joe, and together they embark on an adventure that takes them deep into the heart of Manhattan, and the heart of old-fashioned American ambition. From the shared fears, dreams, and desires of two teenage boys, they spin comic book tales of the heroic, fascist-fighting Escapist and the beautiful, mysterious Luna Moth, otherworldly mistress of the night. Climbing from the streets of Brooklyn to the top of the Empire State Building, Joe and Sammy carve out lives, and careers, as vivid as cyan and magenta ink. Spanning continents and eras, this superb book by one of America’s finest writers remains one of the defining novels of our modern American age.

15: Pachinko by Min Jin Lee (2017)

In the early 1900s, teenaged Sunja, the adored daughter of a crippled fisherman, falls for a wealthy stranger. When she discovers she is pregnant–and that her lover is married–she accepts an offer of marriage from a gentle, sickly minister passing through on his way to Japan. But her decision to abandon her home, and to reject her son’s powerful father, sets off a dramatic saga that will echo down through the generations. Profoundly moving, Pachinko is a story of love, sacrifice, ambition, and loyalty.

14: Outline by Rachel Cusk (2015)

14: Outline by Rachel Cusk (2015)

Rachel Cusk’s Outline is a novel in ten conversations. Spare and lucid, it follows a novelist teaching a course in creative writing over an oppressively hot summer in Athens. She leads her students in storytelling exercises. She meets other visiting writers for dinner. She goes swimming in the Ionian Sea with her neighbor from the plane. The people she encounters speak volubly about themselves: their fantasies, anxieties, pet theories, regrets, and longings. And through these disclosures, a portrait of the narrator is drawn by contrast, a portrait of a woman learning to face a great loss.

13: The Road by Cormac McCarthy (2006)

A father and his son walk alone through burned America. Nothing moves in the ravaged landscape save the ash on the wind. It is cold enough to crack stones, and when the snow falls it is gray. The sky is dark. Their destination is the coast, although they don’t know what, if anything, awaits them there. They have nothing; just a pistol to defend themselves against the lawless bands that stalk the road, the clothes they are wearing, a cart of scavenged food—and each other. The Road is the profoundly moving story of a journey. It boldly imagines a future in which no hope remains, but in which the father and his son, “each the other’s world entire,” are sustained by love. Awesome in the totality of its vision, it is an unflinching meditation on the worst and the best that we are capable of: ultimate destructiveness, desperate tenacity, and the tenderness that keeps two people alive in the face of total devastation.

12: The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion (2005)

Didion’s journalistic skills are displayed as never before in this story of a year in her life that began with her daughter in a medically induced coma and her husband unexpectedly dead due to a heart attack. This powerful and moving work is Didion’s “attempt to make sense of the weeks and then months that cut loose any fixed idea I ever had about death, about illness, about marriage and children and memory, about the shallowness of sanity, about life itself.” With vulnerability and passion, Joan Didion explores an intensely personal yet universal experience of love and loss. The Year Of Magical Thinking will speak directly to anyone who has ever loved a husband, wife, or child.

11: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz (2007)

Oscar is a sweet but disastrously overweight ghetto nerd who—from the New Jersey home he shares with his old world mother and rebellious sister—dreams of becoming the Dominican J.R.R. Tolkien and, most of all, finding love. But Oscar may never get what he wants. Blame the fukú—a curse that has haunted Oscar’s family for generations, following them on their epic journey from Santo Domingo to the USA. Encapsulating Dominican-American history, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao opens our eyes to an astonishing vision of the contemporary American experience and explores the endless human capacity to persevere—and risk it all—in the name of love.

10: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson (2004)

In 1956, toward the end of Reverend John Ames’s life, he begins a letter to his young son, an account of himself and his forebears. Ames is the son of an Iowan preacher and the grandson of a minister who, as a young man in Maine, saw a vision of Christ bound in chains and came west to Kansas to fight for abolition: He “preached men into the Civil War,” then, at age fifty, became a chaplain in the Union Army, losing his right eye in battle. Reverend Ames writes to his son about the tension between his father—an ardent pacifist—and his grandfather, whose pistol and bloody shirts, concealed in an army blanket, may be relics from the fight between the abolitionists and those settlers who wanted to vote Kansas into the union as a slave state. And he tells a story of the sacred bonds between fathers and sons, which are tested in his tender and strained relationship with his namesake, John Ames Boughton, his best friend’s wayward son. This is also the tale of another remarkable vision—not a corporeal vision of God but the vision of life as a wondrously strange creation. It tells how wisdom was forged in Ames’s soul during his solitary life, and how history lives through generations, pervasively present even when betrayed and forgotten.

9: Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro (2005)

As children, Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy were students at Hailsham, an exclusive boarding school secluded in the English countryside. It was a place of mercurial cliques and mysterious rules where teachers were constantly reminding their charges of how special they were. Now, years later, Kathy is a young woman. Ruth and Tommy have reentered her life. And for the first time she is beginning to look back at their shared past and understand just what it is that makes them special—and how that gift will shape the rest of their time together.

8: Austerlitz by W.G. Sebald; translated by Anthea Bell (2001)

A small child when he comes to England on a Kindertransport in the summer of 1939, Jacques Austerlitz is told nothing of his real family by the Welsh Methodist minister and his wife who raise him. When he is a much older man, fleeting memories return to him, and obeying an instinct he only dimly understands, Austerlitz follows their trail back to the world he left behind a half century before. There, faced with the void at the heart of twentieth-century Europe, he struggles to rescue his heritage from oblivion. Over the course of a thirty-year conversation unfolding in train stations and travelers’ stops across England and Europe, W. G. Sebald’s unnamed narrator and Jacques Austerlitz discuss Austerlitz’s ongoing efforts to understand who he is—a struggle to impose coherence on memory that embodies the universal human search for identity.

7: The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead (2016)

Cora is a slave on a cotton plantation in Georgia. An outcast even among her fellow Africans, she is on the cusp of womanhood—where greater pain awaits. And so when Caesar, a slave who has recently arrived from Virginia, urges her to join him on the Underground Railroad, she seizes the opportunity and escapes with him. In Colson Whitehead’s ingenious conception, the Underground Railroad is no mere metaphor: engineers and conductors operate a secret network of actual tracks and tunnels beneath the Southern soil. Cora embarks on a harrowing flight from one state to the next, encountering, like Gulliver, strange yet familiar iterations of her own world at each stop. As Whitehead brilliantly re-creates the terrors of the antebellum era, he weaves in the saga of our nation, from the brutal abduction of Africans to the unfulfilled promises of the present day. The Underground Railroad is both the gripping tale of one woman’s will to escape the horrors of bondage—and a powerful meditation on the history we all share.

6: 2666 by Roberto Bolaño; translated by Natasha Wimmer (2008)

Composed in the last years of Roberto Bolaño’s life, 2666 was greeted across Europe and Latin America as his highest achievement, surpassing even his previous work in its strangeness, beauty, and scope. Its throng of unforgettable characters includes academics and convicts, an American sportswriter, an elusive German novelist, and a teenage student and her widowed, mentally unstable father. Their lives intersect in the urban sprawl of SantaTeresa—a fictional Juárez—on the U.S.-Mexico border, where hundreds of young factory workers, in the novel as in life, have disappeared.

5: The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen (2001)

Enid Lambert is terribly, terribly anxious. Although she would never admit it to her neighbors or her three grown children, her husband, Alfred, is losing his grip on reality. Maybe it’s the medication that Alfred takes for his Parkinson’s disease, or maybe it’s his negative attitude, but he spends his days brooding in the basement and committing shadowy, unspeakable acts. More and more often, he doesn’t seem to understand a word Enid says. Trouble is also brewing in the lives of Enid’s children. Her older son, Gary, a banker in Philadelphia, has turned cruel and materialistic and is trying to force his parents out of their old house and into a tiny apartment. The middle child, Chip, has suddenly and for no good reason quit his exciting job as a professor and moved to New York City, where he seems to be pursuing a “transgressive” lifestyle and writing some sort of screenplay. Meanwhile the baby of the family, Denise, has escaped her disastrous marriage only to pour her youth and beauty down the drain of an affair with a married man—or so Gary hints. Enid, who loves to have fun, can still look forward to a final family Christmas and to the ten-day Nordic Pleasurelines Luxury Fall Color Cruise that she and Alfred are about to embark on. But even these few remaining joys are threatened by her husband’s growing confusion and unsteadiness. As Alfred enters his final decline, the Lamberts must face the failures, secrets, and long-buried hurts that haunt them as a family if they are to make the corrections that each desperately needs.

4: The Known World by Edward P. Jones (2003)

Henry Townsend, a farmer, boot maker, and former slave, through the surprising twists and unforeseen turns of life in antebellum Virginia, becomes proprietor of his own plantation―as well his own slaves. When he dies, his widow Caldonia succumbs to profound grief, and things begin to fall apart at their plantation: slaves take to escaping under the cover of night, and families who had once found love under the weight of slavery begin to betray one another. Beyond the Townsend household, the Known World also unravels: low-paid white patrollers stand watch as slave “speculators” sell free black people into slavery, and rumors of slave rebellions set white families against slaves who have served them for years.

3: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel (2009)

England in the 1520s is a heartbeat from disaster. If the king dies without a male heir, the country could be destroyed by civil war. Henry VIII wants to annul his marriage of twenty years, and marry Anne Boleyn. The pope and most of Europe opposes him. The quest for the king’s freedom destroys his adviser, the brilliant Cardinal Wolsey, and leaves a power vacuum. Into this impasse steps Thomas Cromwell. Cromwell is a wholly original man, a charmer and a bully, both idealist and opportunist, astute in reading people and a demon of energy: he is also a consummate politician, hardened by his personal losses, implacable in his ambition. But Henry is volatile: one day tender, one day murderous. Cromwell helps him break the opposition, but what will be the price of his triumph? In inimitable style, Hilary Mantel presents a picture of a half-made society on the cusp of change, where individuals fight or embrace their fate with passion and courage. With a vast array of characters, overflowing with incident, the novel re-creates an era when the personal and political are separated by a hairbreadth, where success brings unlimited power but a single failure means death.

2: The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson (2010)

With stunning historical detail, Wilkerson tells this story through the lives of three unique individuals: Ida Mae Gladney, who in 1937 left sharecropping and prejudice in Mississippi for Chicago, where she achieved quiet blue-collar success and, in old age, voted for Barack Obama when he ran for an Illinois Senate seat; sharp and quick-tempered George Starling, who in 1945 fled Florida for Harlem, where he endangered his job fighting for civil rights, saw his family fall, and finally found peace in God; and Robert Foster, who left Louisiana in 1953 to pursue a medical career, the personal physician to Ray Charles as part of a glitteringly successful medical career, which allowed him to purchase a grand home where he often threw exuberant parties. Wilkerson brilliantly captures their first treacherous and exhausting cross-country trips by car and train and their new lives in colonies that grew into ghettos, as well as how they changed these cities with southern food, faith, and culture and improved them with discipline, drive, and hard work. Both a riveting microcosm and a major assessment, The Warmth of Other Suns is a bold, remarkable, and riveting work, a superb account of an “unrecognized immigration” within our own land. Through the breadth of its narrative, the beauty of the writing, the depth of its research, and the fullness of the people and lives portrayed herein, this book is destined to become a classic.

1: My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante; translated by Ann Goldstein (2012)

Beginning in the 1950s in a poor but vibrant neighborhood on the outskirts of Naples, Ferrante’s four-volume story spans almost sixty years, as its protagonists, the fiery and unforgettable Lila, and the bookish narrator, Elena, become women, wives, mothers, and leaders, all the while maintaining a complex and at times conflictual friendship. Book one in the series follows Lila and Elena from their first fateful meeting as ten-year-olds through their school years and adolescence. Through the lives of these two women, Ferrante tells the story of a neighborhood, a city, and a country as it is transformed in ways that, in turn, also transform the relationship between her protagonists.

To celebrate TDOV, the

To celebrate TDOV, the

Every year I like to celebrate Jane Austen’s birthday with a blog post highlighting interesting things to read and new books that have been published about her, so here is this year’s list:

Every year I like to celebrate Jane Austen’s birthday with a blog post highlighting interesting things to read and new books that have been published about her, so here is this year’s list:

Get in the Halloween spirit with the

Get in the Halloween spirit with the

A Page from Jane Austen’s handwritten music book

A Page from Jane Austen’s handwritten music book

When British poet Amy Key was growing up, she envisioned a life shaped by love–and Joni Mitchell’s album

When British poet Amy Key was growing up, she envisioned a life shaped by love–and Joni Mitchell’s album

The automobile was one of the most miraculous inventions of the 20th century. It promised freedom, style, and utility. But sometimes, rather than improving our lives, technology just makes everything worse. Over the past century, cars have filled the air with toxic pollutants and fueled climate change. Cars have stolen public space and made our cities uglier, dirtier, less useful, and more unequal. Cars have caused tens of millions of deaths and injuries. They have wasted our time and our money. In

The automobile was one of the most miraculous inventions of the 20th century. It promised freedom, style, and utility. But sometimes, rather than improving our lives, technology just makes everything worse. Over the past century, cars have filled the air with toxic pollutants and fueled climate change. Cars have stolen public space and made our cities uglier, dirtier, less useful, and more unequal. Cars have caused tens of millions of deaths and injuries. They have wasted our time and our money. In  The Ramirez women of Staten Island orbit around absence. When thirteen‑year‑old middle child Ruthy disappeared after track practice without a trace, it left the family scarred and scrambling. One night, twelve years later, oldest sister Jessica spots a woman on her TV screen in Catfight, a raunchy reality show. She rushes to tell her younger sister, Nina: This woman’s hair is dyed red, and she calls herself Ruby, but the beauty mark under her left eye is instantly recognizable. Could it be Ruthy, after all this time?

The Ramirez women of Staten Island orbit around absence. When thirteen‑year‑old middle child Ruthy disappeared after track practice without a trace, it left the family scarred and scrambling. One night, twelve years later, oldest sister Jessica spots a woman on her TV screen in Catfight, a raunchy reality show. She rushes to tell her younger sister, Nina: This woman’s hair is dyed red, and she calls herself Ruby, but the beauty mark under her left eye is instantly recognizable. Could it be Ruthy, after all this time?

“Art and nature shall always be wrestling until they eventually conquer one another so that the victory is the same stroke and line: that which is conquered, conquers at the same time.” – Merian

“Art and nature shall always be wrestling until they eventually conquer one another so that the victory is the same stroke and line: that which is conquered, conquers at the same time.” – Merian

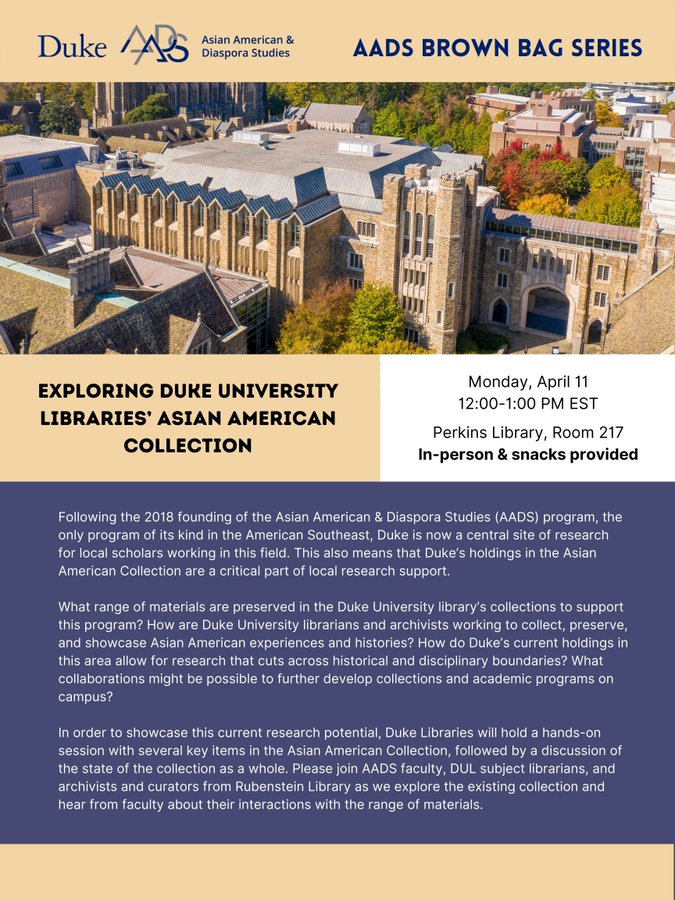

Growing up in the American South, finding community with other Filipino Americans often felt difficult, especially compared to my relatives living in Filipino enclaves on the West Coast. Thus, when I chose to attend a Southeastern university like Duke, it was no surprise when I found little Filipino presence on campus, both in academics and in campus life (though it should be noted, there has been progress in this area even just in my short time on campus, such as the development of a Filipino student group and the approval of the

Growing up in the American South, finding community with other Filipino Americans often felt difficult, especially compared to my relatives living in Filipino enclaves on the West Coast. Thus, when I chose to attend a Southeastern university like Duke, it was no surprise when I found little Filipino presence on campus, both in academics and in campus life (though it should be noted, there has been progress in this area even just in my short time on campus, such as the development of a Filipino student group and the approval of the

In

In

Ada Limòn was recently

Ada Limòn was recently

Cover image for Moustafa Bayoumi’s

Cover image for Moustafa Bayoumi’s

ONLINE: Meet Threa Almontaser, Rosati Visiting Writer

ONLINE: Meet Threa Almontaser, Rosati Visiting Writer

Throughout my time at Duke, I have grounded myself in the study of race and racism. But class after class, I found myself being the voice at the back of the room asking about Latinx populations. Constantly pushing back against the idea that the story of race and racism is strictly Black-White, when it came time to finally decide what I would write my thesis on (something I knew would happen before I even decided to come to Duke), I figured since I have been doing this work for three years, I might as well make it official in my last year here. And so came my summer research project that I used to step into this mystical world that would become my history thesis.

Throughout my time at Duke, I have grounded myself in the study of race and racism. But class after class, I found myself being the voice at the back of the room asking about Latinx populations. Constantly pushing back against the idea that the story of race and racism is strictly Black-White, when it came time to finally decide what I would write my thesis on (something I knew would happen before I even decided to come to Duke), I figured since I have been doing this work for three years, I might as well make it official in my last year here. And so came my summer research project that I used to step into this mystical world that would become my history thesis.

South Africa has a unique history in the development of human rights, which is very clear in their constitution, which grants freedoms and protections of various identities, regardless of citizenship. Because of this, South Africa becomes the place where many African queer migrants and asylum seekers come to seek refuge. However, the rise of queer-phobic and xenophobic violence has questioned the power of laws to translate to lived experiences, leading many to have to navigate the refugee process surrounded by prejudice. Their dual identity makes it difficult to find community with queer South Africans or their cisgender/heterosexual fellow refugees and families. Due to the history of colonialism in South Africa, many of the barriers they face are physically constructed into urban cities, affecting access to resources, work opportunities, and how communities are formed, which forces them to navigate through life in ways where they must think about the presentation of their identities in any given space.

South Africa has a unique history in the development of human rights, which is very clear in their constitution, which grants freedoms and protections of various identities, regardless of citizenship. Because of this, South Africa becomes the place where many African queer migrants and asylum seekers come to seek refuge. However, the rise of queer-phobic and xenophobic violence has questioned the power of laws to translate to lived experiences, leading many to have to navigate the refugee process surrounded by prejudice. Their dual identity makes it difficult to find community with queer South Africans or their cisgender/heterosexual fellow refugees and families. Due to the history of colonialism in South Africa, many of the barriers they face are physically constructed into urban cities, affecting access to resources, work opportunities, and how communities are formed, which forces them to navigate through life in ways where they must think about the presentation of their identities in any given space.