This press release is in Haitian Creole as well as English. Scroll down for Haitian Creole.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 9 April 2018

Duke University Libraries

Media Contact: Aaron Welborn, (919) 660-5816

Email: aaron.welborn@duke.edu

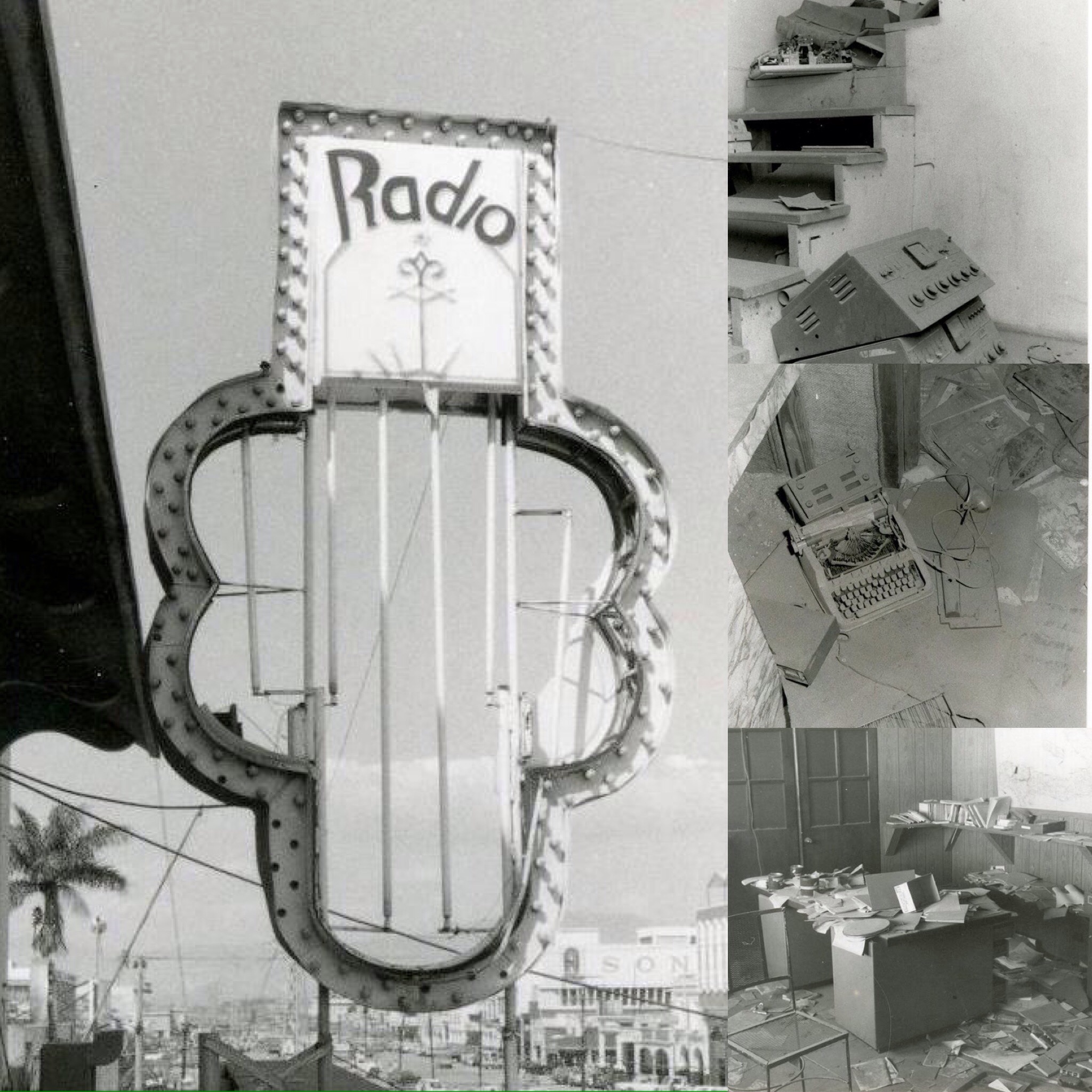

Radio Haiti Archive receives second National Endowment for the Humanities grant

Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grant will enable continued in-depth description of the audio archive of Radio Haïti-Inter

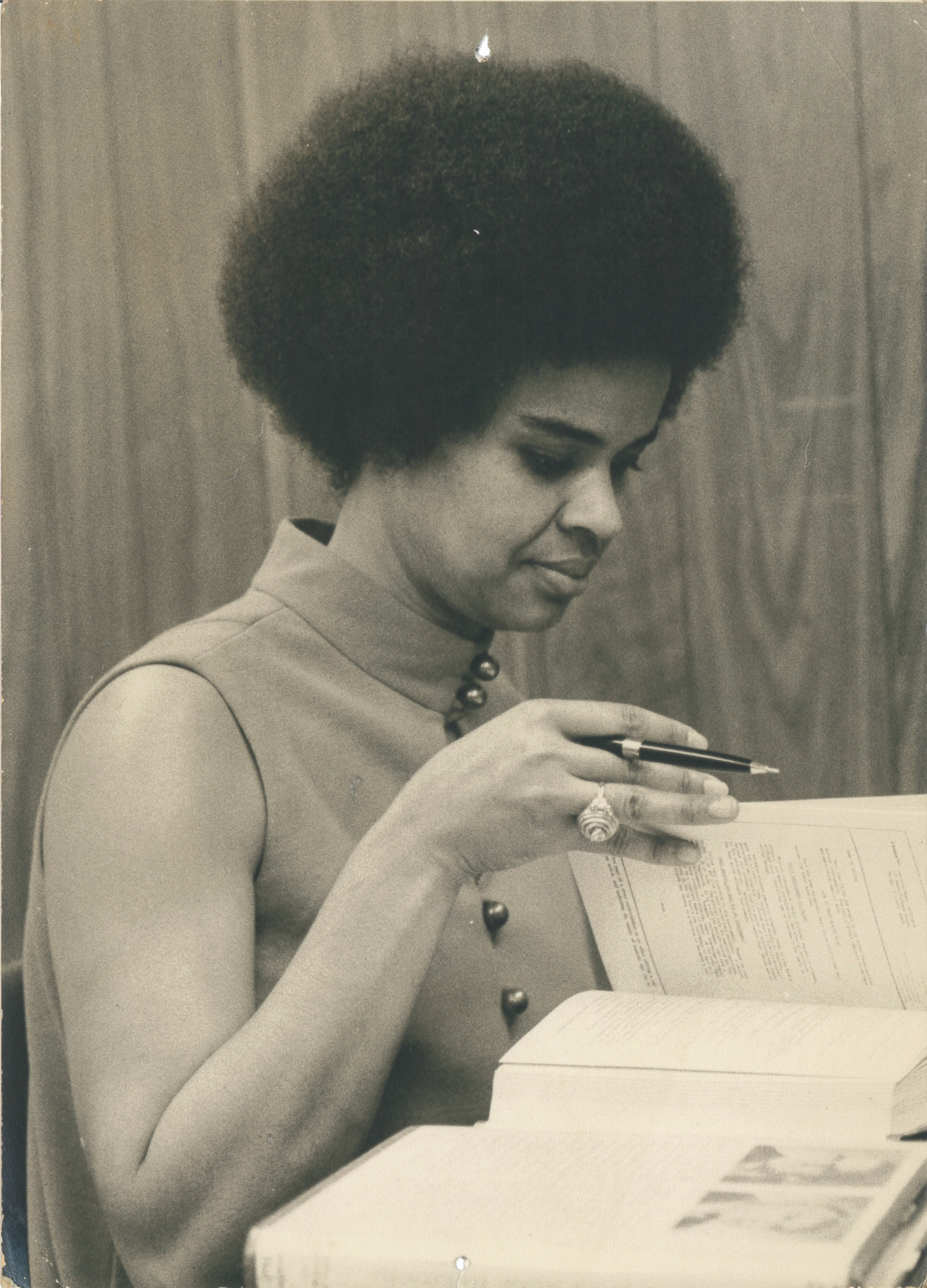

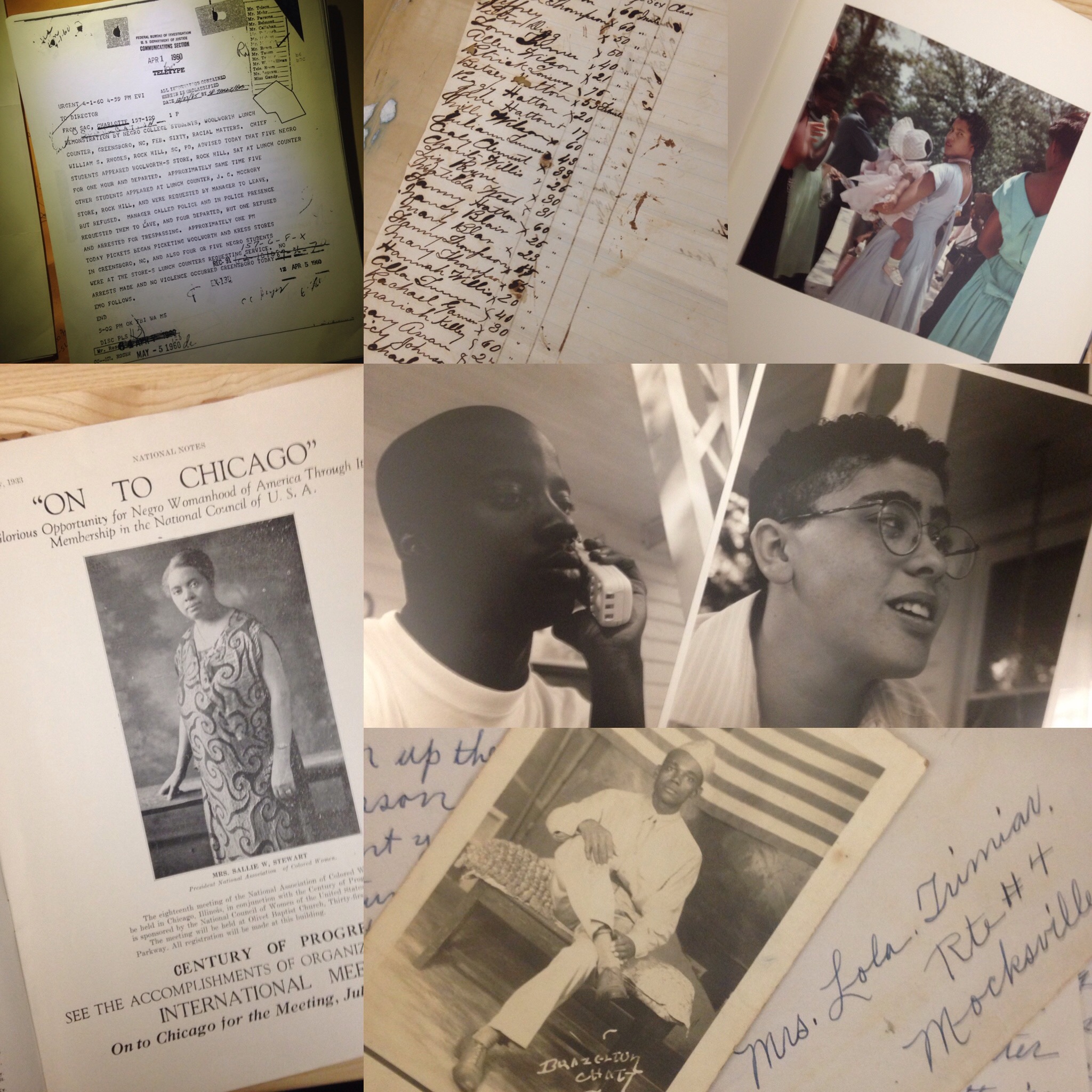

Durham, NC: The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce that the Radio Haiti Archive project has received a second grant from the NEH’s Division of Preservation and Access. While the first phase of the project, Radio Haiti, Voices of Change, focused on the physical preservation and initial description of the Radio Haiti materials, Radio Haiti, Voices of Change II: Bringing Radio Haiti Home will allow library staff to continue creating detailed trilingual description of Radio Haiti’s audio (in Haitian Creole, French, and English) and to digitally repatriate the archive to libraries, archives, cultural institutions, and community radio stations in Haiti.

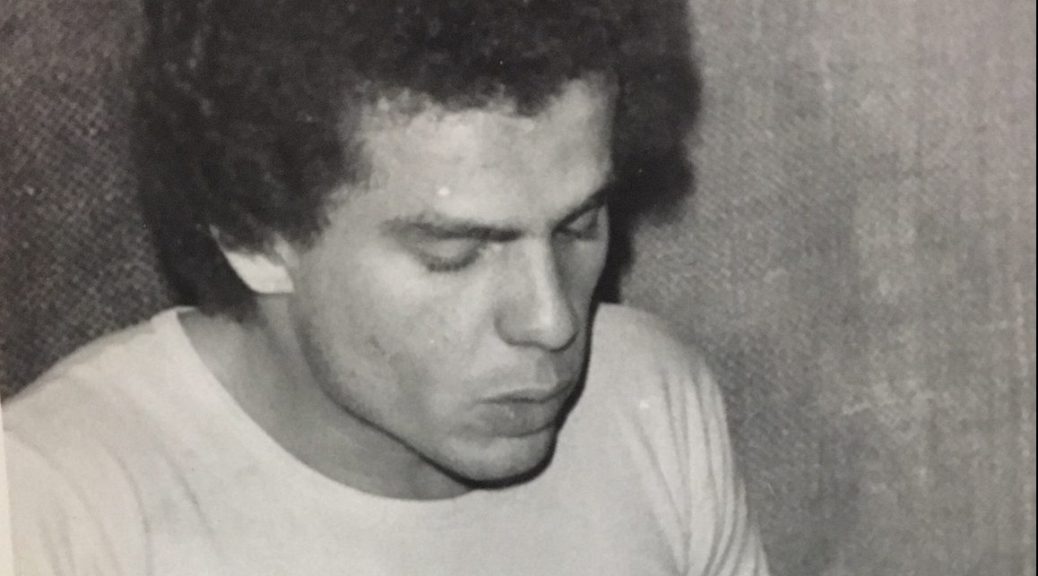

For three decades, Radio Haïti-Inter was Haiti’s first and most prominent independent radio station. Under the direction of Jean Léopold Dominique and Michèle Montas, Radio Haiti was a voice of social change and democracy, speaking out against oppression and impunity while advocating for human rights and celebrating Haitian culture and heritage. On 3 April 2000, Jean Dominique was assassinated in Radio Haiti’s courtyard, and in February 2003, amid escalating threats to Radio Haiti’s journalists, the station closed for good.

Laurent Dubois, professor of history and Romance Studies and the director of Duke’s Forum for Scholars and Publics, describes Voices of Change II as a “vital project that will allow this rich archive to be made available as widely as possible, notably in Haiti itself. This is of profound importance, for having learned over the past years about the richness of the materials in the Radio Haiti collection, I consider it the most important archive on contemporary Haitian politics, history, and culture in existence.” In the words of the station’s surviving director, Michèle Montas: “It is so important that these voices, which have meant so much to so many, remain alive and vibrant in the land that created them.”

—

To follow the Radio Haiti project’s progress and consult the materials, see the Radio Haiti collection on Duke’s Digital Repository and the Guide to the Radio Haiti Papers.

Pwojè Achiv Radyo Ayiti jwenn yon dezyèm sibvansyon National Endowment for the Humanities

Sibvansyon Humanities Collections and Reference Resources pral pemèt nou kontinye dekri achiv odyo Radyo Ayiti-Entè yo an detay

Durham, Karolin di Nò: Se avèk anpil kè kontan David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library (Bibliyotèk David M. Rubenstein pou Liv ak Maniskri ki Ra) anonse ke pwojè Achiv Radyo Ayiti a jwenn yon dezyèm sibvansyon NEH, nan kad Division of Preservation and Access (Divizyon Konsèvasyon ak Aksè). Tandiske premye etap pwojè a, Radio Haiti, Voices of Change (Radyo Ayiti: Vwa Chanjman) te konsantre sou konsèvasyon fizik ak deskripsyon preliminè achiv Radyo Ayiti yo, dezyèm etap la, ki rele Radio Haiti, Voices of Change II: Bringing Radio Haiti Home (Radyo Ayiti, Vwa Chanjman II: Mennen Radyo Ayiti Tounen Lakay Li) pral pemèt manm staf bibliyotèk la kontinye bay chak emisyon Radyo Ayiti deskripsyon detaye nan twa lang yo (kreyòl, franse, ak angle) epi repatriye achiv yo nan bibliyotèk, achiv, enstitisyon kiltirèl, ak radyo kominotè ann Ayiti.

Radyo Ayiti-Entè te premye radyo endepandan nan peyi d Ayiti, epi pandan trant ane li te pi koni pami tout radyo nan peyi a. Anba direksyon Jean Léopold Dominique ak Michèle Montas, Radyo Ayiti te reprezante yon vwa chanjman ak demokrasi, ki te konn denonse sistèm kraze zo ak enpinite, lite pou dwa moun, epi valorize kilti ak eritaj Ayiti a. Jou 3 avril 2000, yo te krabinen Jean Dominique nan lakou Radyo Ayiti a, epi nan mwa fevriye 2003, kòm rezilta yon dal menas jounalis Radyo Ayiti yo t ap sibi, radyo a fèmen nèt.

Laurent Dubois, pwofesè istwa ak etid lang latin yo epi direktè Forum for Scholars and Publics nan Inivèsite Duke, dekri pwojè Voices of Change II kòm yon “pwojè fondalnatal ki pral rann achiv rich disponib osi lwen ke posib, sitou ann Ayiti menm. M twouve sa gen anpil enpòtans. Pandan plizyè ane m ap aprann ki richès achiv Radyo Ayiti yo gen ladan yo, ki fè m konsidere l kòm achiv ki pi enpòtan sou politik, istwa, ak kilti Ayiti kontanporen ki egziste sou latè beni.” Nan pawòl Michèle Montas, antanke direktris sivivan radyo a: “Li kapital ke vwa sa yo, ki gen anpil enpòtans pou anpil moun, toujou rete vivan ak vif nan peyi ki te kreye yo.”

—

Pou swiv pwogrè pwojè Radyo Ayiti a epi pou sèvi avèk achiv yo, tcheke koleksyon Radyo Ayiti nan Duke Digital Repository ak Gid pou Papye Radyo Ayiti yo.

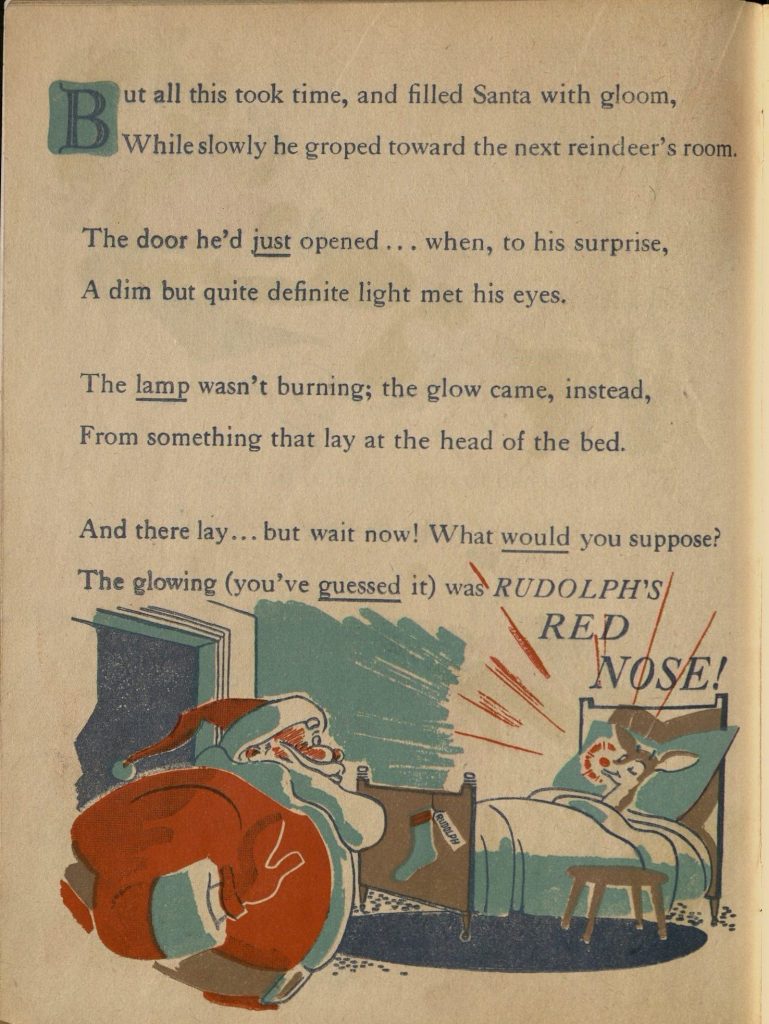

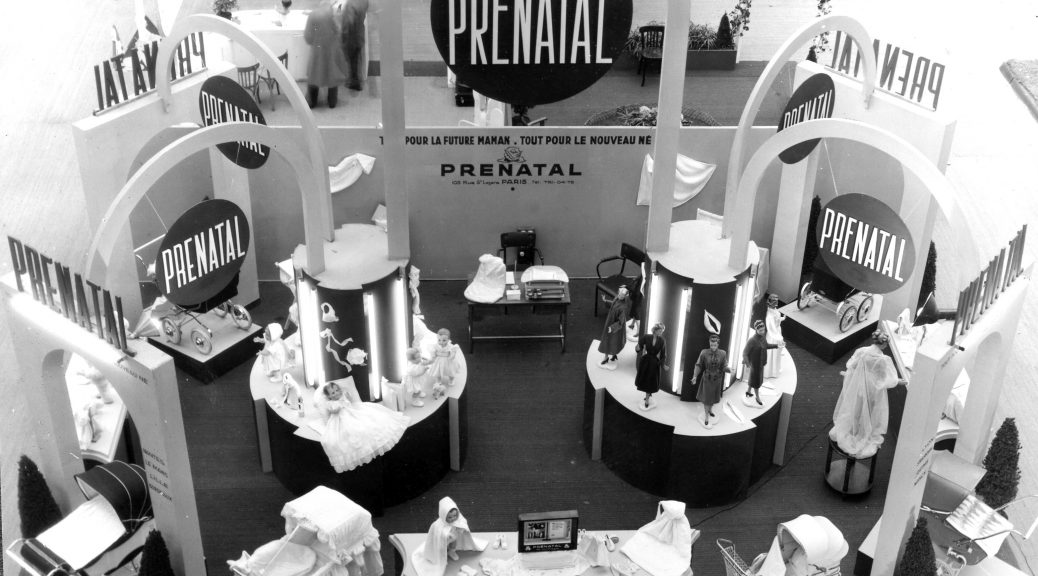

Just in time for the holiday season, the Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History in the David M. Rubenstein Library has acquired a copy of

Just in time for the holiday season, the Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History in the David M. Rubenstein Library has acquired a copy of