Post contributed by Claire Payton, John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History intern and Ph.D. candidate, Duke University Department of History

At the end of World War II, the meaning of family changed in profound ways. In Europe and North America, young couples set about starting new families. Their enthusiasm for procreation generated the demographic explosion known as the “baby boom.” Those who could afford it filled their homes with refrigerators, television sets, and baby toys, midwifing another major post-war transformation: the rise of consumerism.

Riding these twin dynamics, an upstart Parisian advertising firm was able to build up a small French company into a famous international brand. Publicis was a small ad firm founded in 1926 by Marcel Blustein-Blanchet, the son of Jewish immigrants. Blustein-Blanchet managed to flee when the Nazis occupied France in 1940. Publicis was shuttered and the office and equipment were seized by the government. But when the war ended he returned and, in 1946, reopened Publicis. One of the first new clients he signed while rebuilding from scratch was a small new company that specialized in maternity clothes called Prénatal.

Founded by Jean-Maire Mazart in 1947, Prénatal seized upon the social transformations of the era. With the help of Publicis, the company targeted young pregnant women who were looking to overcome the war through the power of consumerism. Mazart’s idea, inspired by the United States, was to provide women with high-end clothes in different sizes depending on how far along they were in their pregnancy. The idea was an immediate hit in France, and Prénatal expanded quickly. It diversified its products to include baby items so that loyal clients could continue to have things to buy things even after pregnancy was over and motherhood began. Within two decades, there were two hundred Prénatal storefronts in France, with more around Europe and overseas.

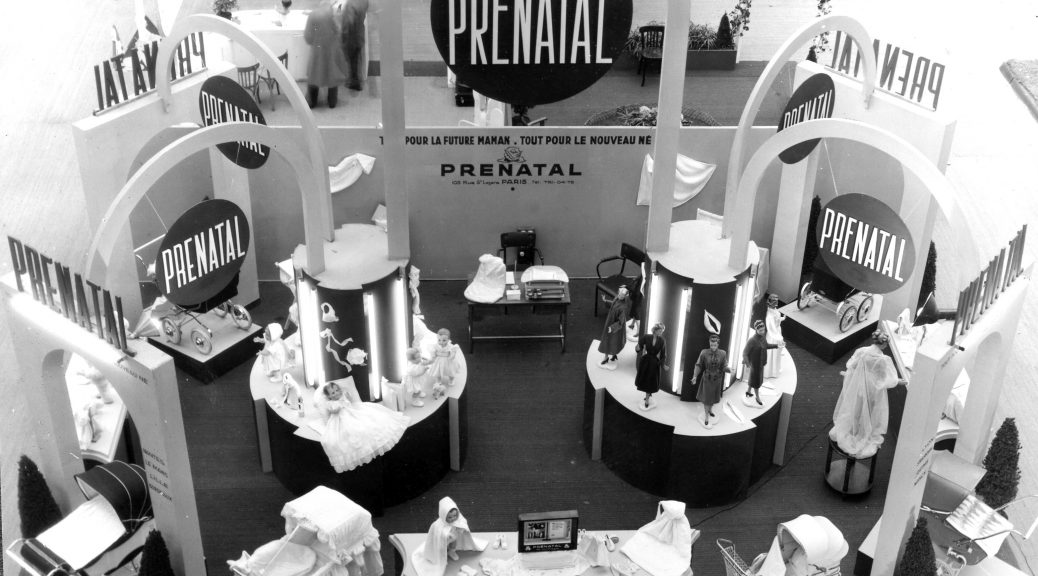

One of the ways Publicis drummed up excitement for its clients was to design large displays at major marketing events. These photos show its Prénatal installation at a 1950s Foire de Paris (Paris Fair) which was held in the luminous Parisian marketplace, Les Halles. The photos are part of a new acquisition at the Hartman Center, a Collection of French Advertising Display Binders that feature photos of Publicis advertisements, installations, and displays from the 1950s. The Publicis-Prénatal strategy is evident in the slogan painted on the walls: “Tout pour la future maman…Tout pour le nouveau ne” (Everything for the mom-to-be…Everything for the newborn). The design of the Prénatal display showcased the message that ideal mid-century motherhood–glamorous, clean, elegant–was available with the signing of a check.

By the late 1960s, the message pedaled by Prénatal and Publicis had lost some of its charm. The very people who might have worn Prénatal clothes as infants grew up to challenge post-war ideas of consumerism and the heteronormative nuclear family that the company’s products celebrated. With the increasing availability of contraceptives in the late 1960s, women could aspire to more than a fashionable and well-heeled pregnancy. Mazart sold the company in 1972; it closed its last doors in 1997. More able than its client to adapt to changing cultural norms, Publicis today is one of the world’s leading multinational advertising and public relations agencies.