Post contributed by Lucy Dong, Middlesworth Social Media and Outreach Fellow

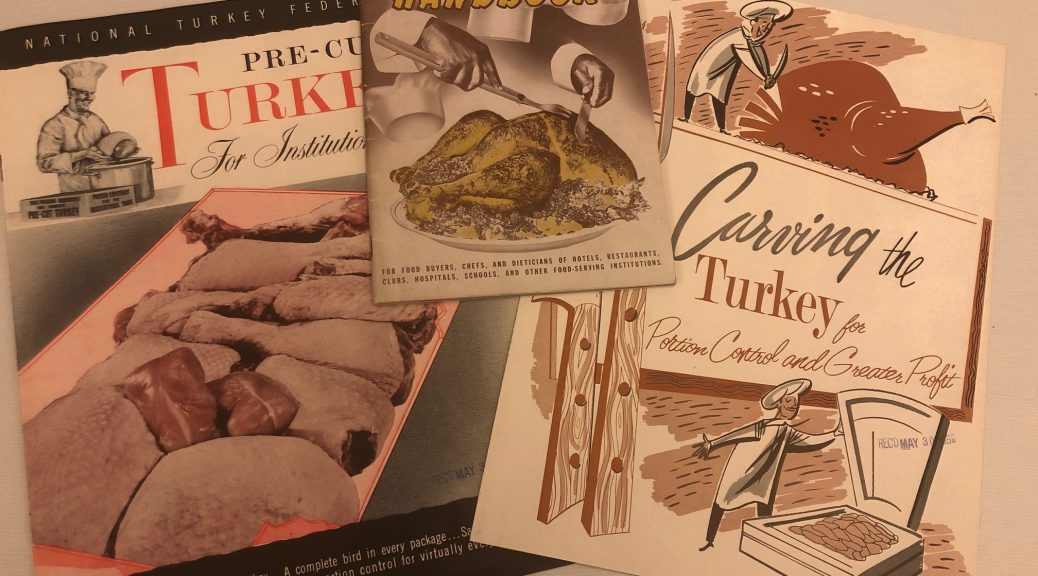

The Nicole Di Bona Peterson Collection of Advertising Cookbooks is a frequent source of test kitchen projects, featuring members of the Rubenstein staff documenting their attempts to create delicious and sometimes very odd recipes. We were inspired by the popularity of Buzzfeed Tasty and Bon Appetit cooking videos, however, to show a test kitchen that was fast and digestible. With their simple captions, overhead angle, sped up chopping, and quirky music, the cooking videos trending on social media are made to grab your short attention. And what better attention grabber than a triple tiered Jell-O cake and a Jell-O salad?

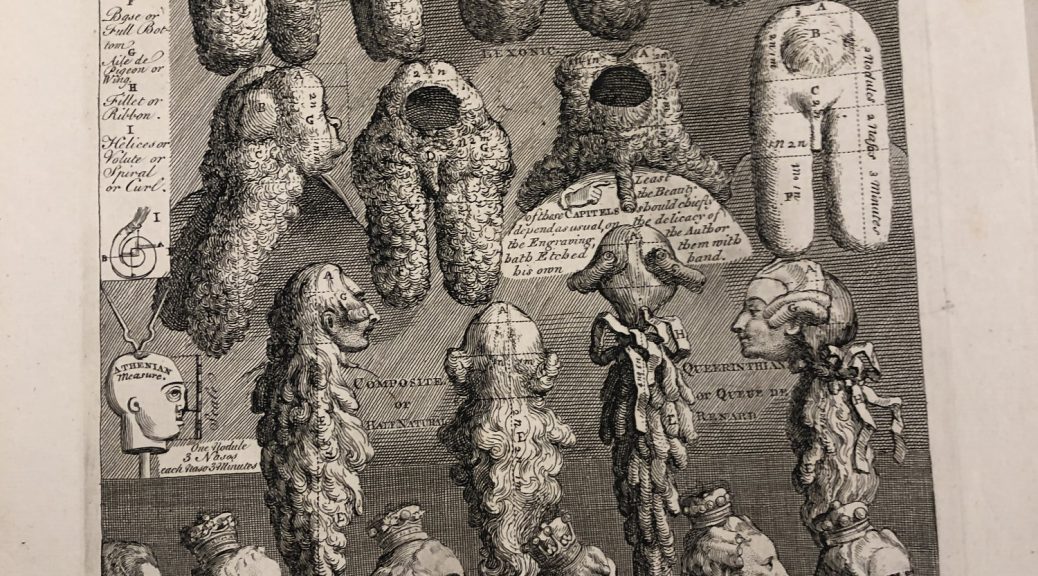

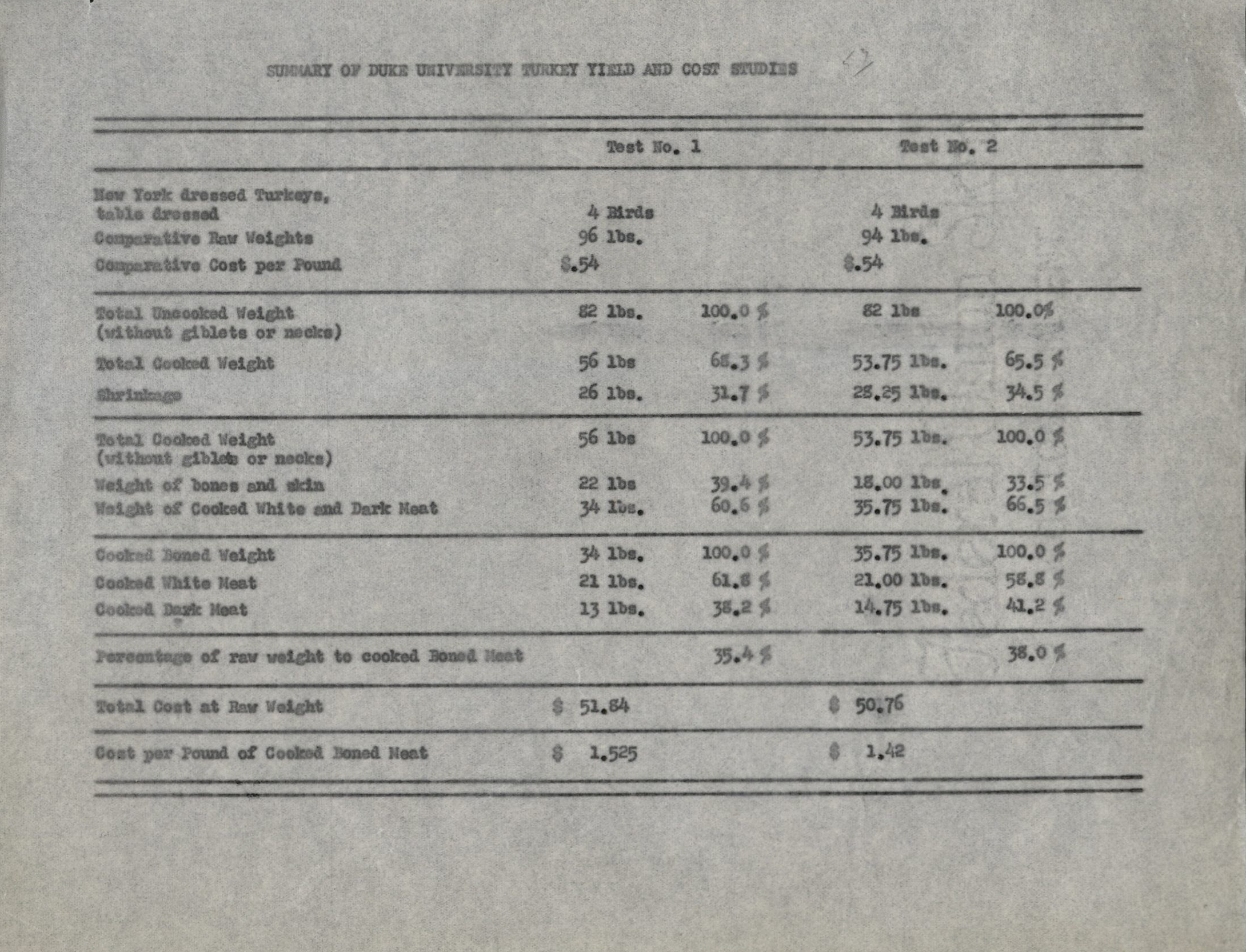

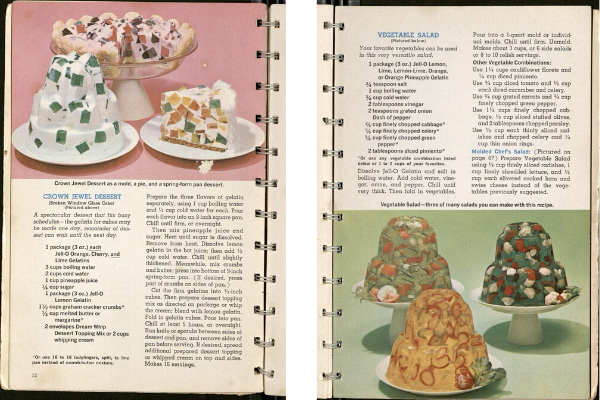

Lucky for us, many people have abandoned their fish molds of kitchens past, and my cooking partner, Sonia Fillipow, was able to find one easily at the Durham Scrap Exchange. The triple tiered molds were harder to find so we settled on a recipe that could look colorful and exciting in one layer. Old recipes often use unfamiliar jargon or lack specifics, and test kitcheners have sometimes had to do some educated guesswork or extra research. The recipe book we referenced, “Joys of Jell-O Gelatin Dessert” (1962) includes a very helpful graphic for how long you should chill your Jello to achieve your desired consistency. Our molds held much more Jell-O than the recipe created, so we had to do some math. Getting the Jell-O out of the molds was a whole other ordeal that we were not prepared for–we decided to save you from our failed attempts in the final cut.

Along the way, we got to learn some of the history of Jell-O. The Nicole Di Bona Peterson Collection of Advertising Cookbooks spans the years 1851-2005 and covers promotional materials addressed to cooking and kitchen arts. Materials in the collection were used to educate consumers and promote the use of a variety of foods. “Joys of Jell-O Gelatin Dessert” (1962) was one such educational recipe book that served marketing purposes. As seen in this early 20th-century when the owner of Jell-O, Otto Frank Woodward, invested in advertising that proclaimed it to be ‘America’s Most Famous Dessert’, marketing was crucial to getting the gelatin product into American kitchens. Woodward published recipe books, handed out Jell-O molds to immigrants, and aired a jingle on the radio. The brand’s messaging towards women has changed over the years, but perhaps the one thing that hasn’t changed its aesthetic potential. As the New York Times reports, “queer and female artists are now revisiting Jell-O as both subject matter and material, creating work that challenges society’s fixations on traditionally feminine realms and behaviors.”

We lack the artistic talent to make stunning Jell-O art worthy of fashion campaigns, but thanks to a lot of patience, and some YouTube tutorials on removing Jell-O from Jell-O molds, we ended up with a ‘cake’ and a ‘salad’ that looked great (and the Crown Jewel cake even tasted okay).

Recipes:

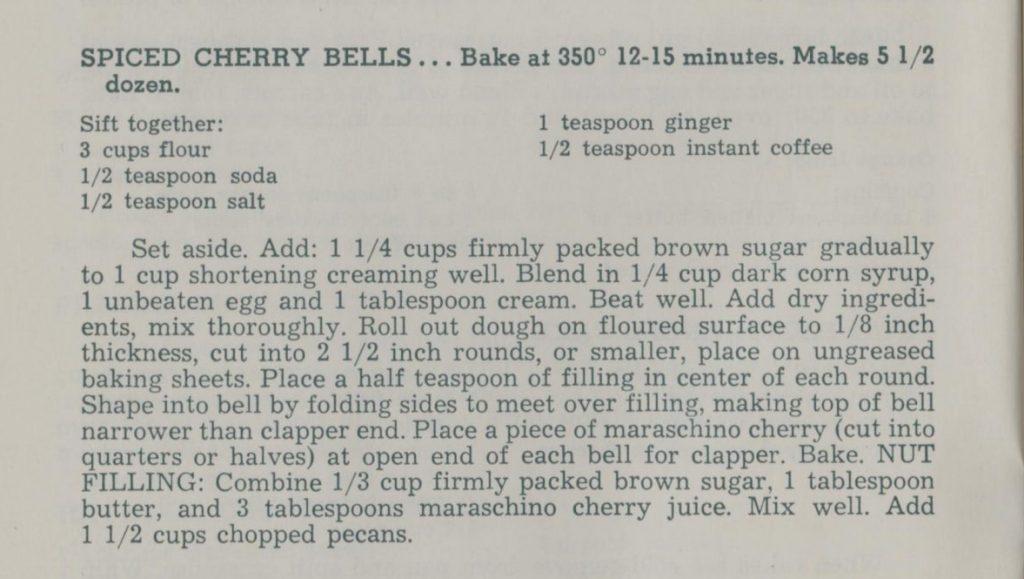

Crown Jewel Dessert / “Broken Window Glass Cake”

“A spectacular dessert that fits busy schedules–the gelatin for cubes may be made on day, remainder of dessert can wait until the next day.”

1 package (3 oz.) EACH of 3 different flavored (and different colored) Jell-O

3 cups boiling water

2 cups cold water

1 cup pineapple juice

¼ cup sugar

1 package (3 oz.) Jell-O Lemon Gelatin

2 envelopes Dream Whip Dessert Topping Mix or 2 cups whipping cream

- Prepare the three flavors of gelatin separately, using 1 cup of boiling water and ½ cup cold water for each. Pour each flavor into an 8-inch square pan or tupperware. Chill until firm, or overnight.

- Mix pineapple juice and sugar; heat until sugar is dissolved. Remove from heat and dissolve lemon gelatin in the hot juice; then add ½ cup cold water. Chill until slightly thickened.

- Prepare dessert topping mix as directed on package and blend with slightly thickened lemon gelatin.

- Cut firm gelatins into ½ – inch cubes. Layer cubes in Jell-O mold with cream/gelatin mixture so that the cubes are relatively dispersed throughout. Chill at least 5 hours or overnight.

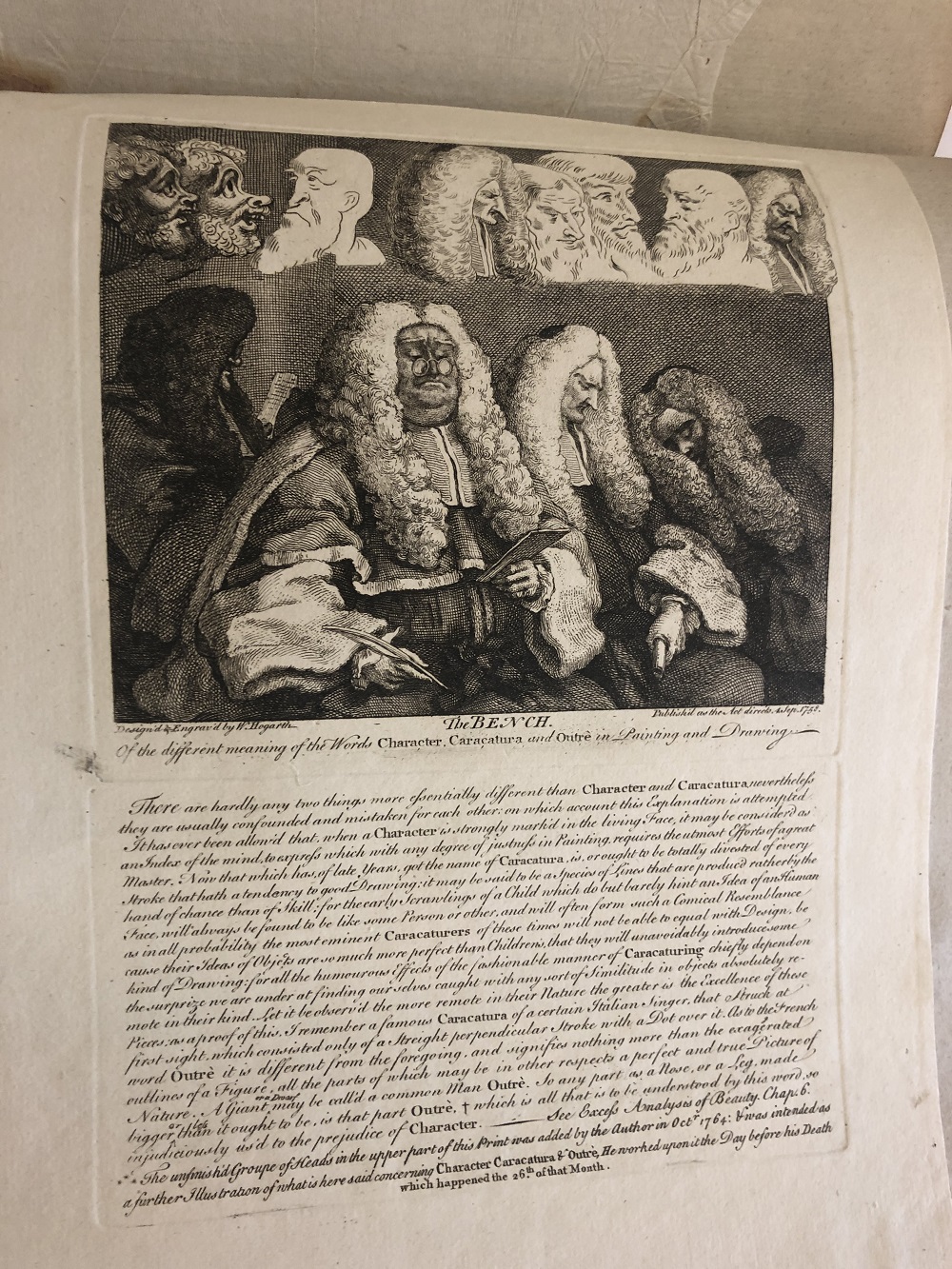

- When removing dessert from mold, submerge the bottom of the mold in a bowl of hot tap water for 5-10 sec. Separate the gelatin from the edges of the mold either by running a knife/spatula between the dessert and the mold or gently pulling at the edge with the flat part of the fingers. Place a plate (or a clean cutting board) on top of the mold and invert. Other tips from the book pictured below. You can also use this video for reference.

Vegetable Salad

“Your favorite vegetable can be used in this very versatile salad”

1 package (3 oz.) Jell-O; any citrus flavored gelatin like lemon or lime

¼ teaspoon salt

1 cup boiling water

2 tablespoons vinegar

2 teaspoons grated onion

1 dash of pepper

1-2 cups of any 3 vegetables, chopped finely

- Dissolve Jell-O Gelatin and salt in boiling water. Add cold water, vinegar, grated onion, and pepper. Pour into fish mold and chill until very thick.

- Chop vegetables into matchsticks or florets.

- Fold chopped vegetables into thickened gelatin and chill overnight.

- Unmold