Post contributed by Elliot Mamet, Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at Duke and Archival Processing Intern at the Rubenstein Library.

What does it feel like to be a fly on the wall at the Nuremberg Trials? The papers of Robert P. Stewart, recently donated to the Rubenstein Library, provide an answer.

Stewart was an attorney and Duke alumnus who served as a legal aide to Judge John J. Parker at the Nuremburg Trials in 1945 and 1946. There, 24 Nazi political and military leaders were indicted and tried with waging aggressive war, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. 19 were found guilty, and 12 were sentenced to death.

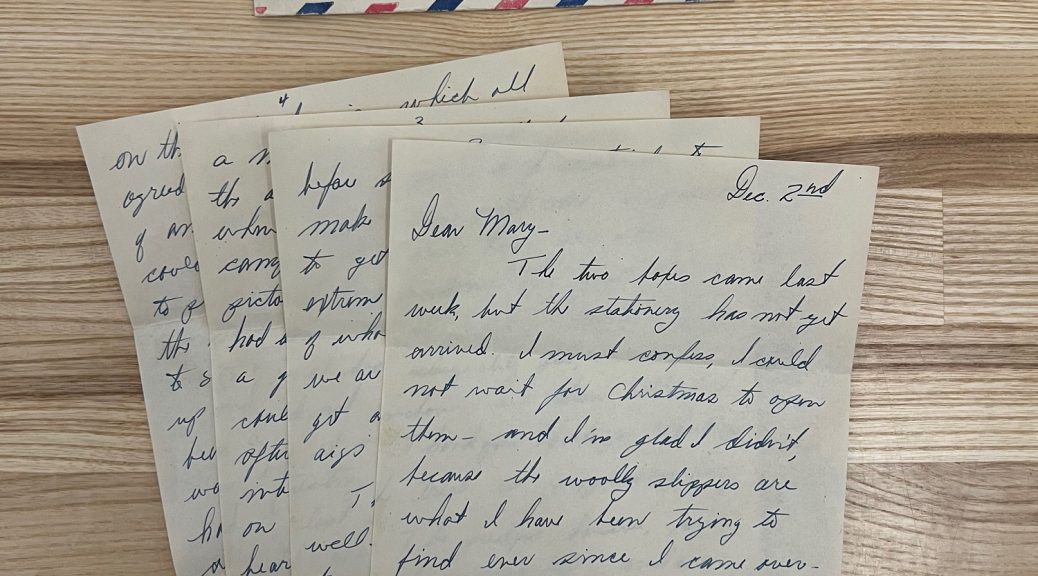

An overriding theme of Stewart’s correspondence is the emotional toll that the evidence of Nazi crimes took on the jurists. His letters tell of film evidence taken by the U.S. army when they first encountered the Nazi concentration camps. “It really was an awful pictorial display of what the Nazis had done—and it upset Judge [Parker] a great deal. The English judges could not even eat.”[1] Judge Parker, Stewart says, became depressed from hearing so much terrible evidence.[2] Compounding this emotional toll was the homesickness felt by the American legal contingent.

Also in Stewart’s letters is discussion of the secret 1939 non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the USSR—an agreement first disclosed at Nuremberg. Writes Stewart, “perhaps the most interesting bit behind the scenes lately is the way one of the defense lawyers is trying to introduce a document which purports to be a photostat copy of a secret treaty between Germany and Russia in 1939.”[3] That non-aggression pact paved the way for the Nazi invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939.

Outside of court, Stewart encountered colorful characters during his service at Nuremberg. For instance, he lunched with General Dwight Eisenhower at Eisenhower’s Frankfurt villa, calling Eisenhower “a remarkable man—strictly down to earth,” and noting it was “probably the first time during this war that anyone so lowly as a major sat down to break bread with him.”[4]

Some 35 years after returning from the Nuremberg Trials, Stewart reflected on his service in a profile in The Asheville Citizen. “The most dramatic part of the trials,” Stewart said, “was the evidence on the persecution of the Jews. The films shown and the stories told were horrendous, unbelievable. If I hadn’t been there I would never have believed it.”[5] He was there, and his papers at the Rubenstein help us feel what it was like.

Footnotes:

[1] Letter from Robert P. Stewart to Beverly G. Moss, December 2, 1945. Folder 2, Robert P. Stewart papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

[2] Letter from Robert P. Stewart to Plummer Stewart, January 12, 1946. Folder 2, Robert P. Stewart papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

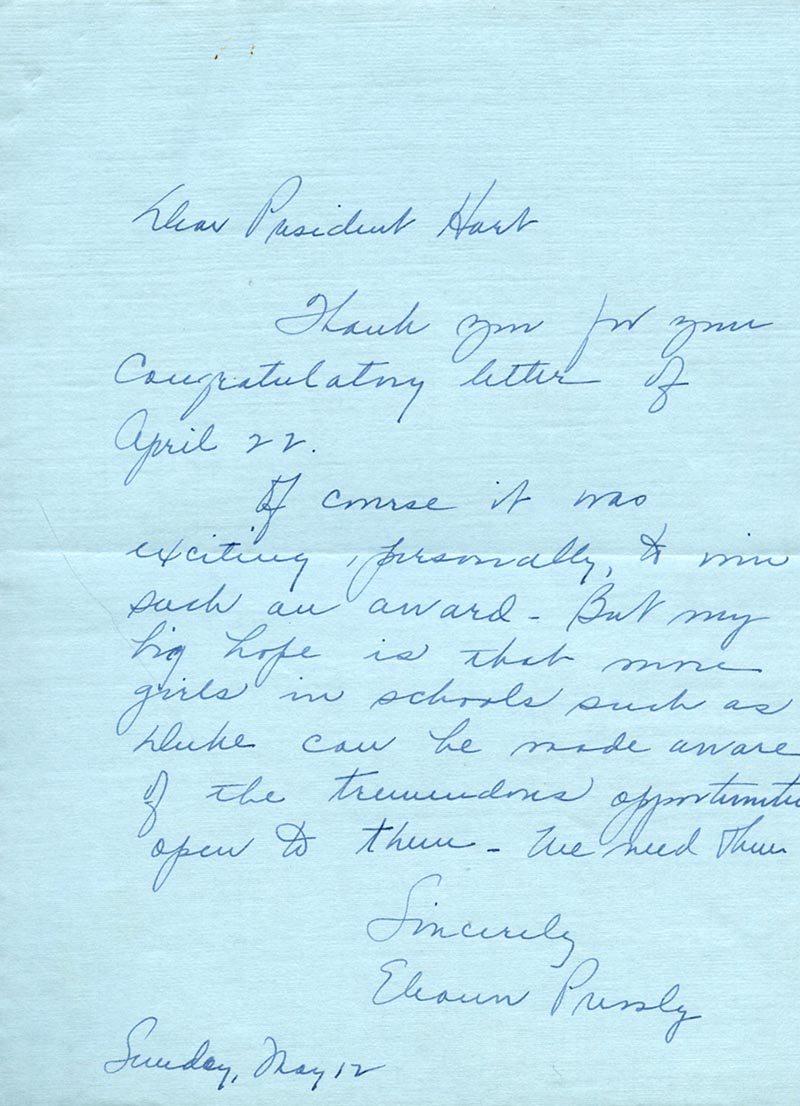

[3] Letter from Robert P. Stewart to Plummer Stewart, May 30, 1946. Folder 3, Robert P. Stewart Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

[4] Letter from Robert P. Stewart to Plummer Stewart, November 7, 1945, and letter from Robert P. Stewart to C. C. Gabel, November 7, 1945. Folder 1, Robert P. Stewart papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

[5] Tony Brown, “Stewart Had Important Role at Nuremberg,” The Asheville Citizen, September 8, 1981, pg. 9. Oversize Folder 1, Robert P. Stewart papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.