Blog post contributed by Liz Adams, Rare Materials Cataloger

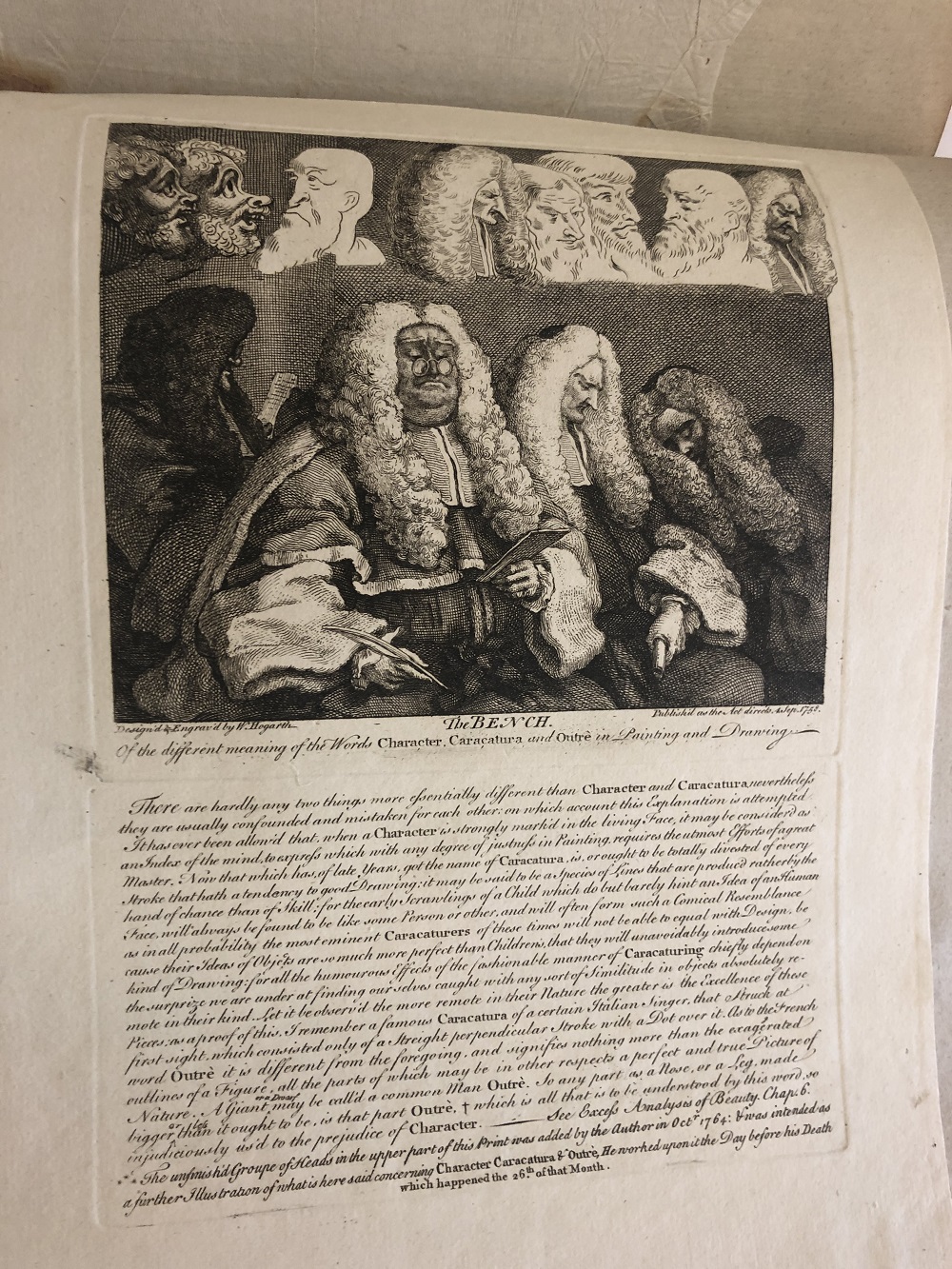

Way back in 2018, back when the new decade was but a glint in our eyes, we received something very big (literally and metaphorically) here at the Rubenstein: a single volume of 83 prints associated with William Hogarth. The creation dates for these prints span from 1732 (Midnight modern conversation) to 1781 (Mr. Walpole). Some of them are sincere, like a portrait of the actor David Garrick as Richard III. Others chart corruption and vice, notably in the series A rake’s progress and A harlot’s progress. Still others are pointed rejoinders to Hogarth’s nemeses, which included people like the satirist Charles Churchill (The bruiser, C. Churchill), alcoholic beverages (Gin Lane), and the French military. The themes are varied; the production methods evolve; and even Hogarth’s role in the creation of these prints oscillates between publisher, printer, artist of original work, and artistic supervisor. The prints are thus unified by their differences.

In 2019, I learned these differences were not just between prints but also within them. Hogarth was a tinkerer: He would return to the same copper plate, darkening and expanding shadows, adding crosshatching, changing clothing and facial features, and even excising text. He would do this work multiple times, releasing subsequent editions, or “states” of each print. There are at least ten different versions of some of Hogarth’s most famous prints, all subtly different and requiring the viewer to have excellent “I spy” skills. Luckily (for me and you, but mostly me), Hogarth is a very famous and well-studied artist. Dr. Ronald Paulson’s Hogarth’s graphic works tracks every change, making it possible to differentiate between moderate cross-hatching and slightly deeper cross-hatching. Thanks, Dr. Paulson!

I want to point out just one more wrinkle: After Hogarth’s death in 1764, his copper plates first went to his family, who then sold them to the publisher John Boydell. In 1790, Boydell published a volume of Hogarth’s works using the unaltered copper plates. Thus, a print that might be physically dated 1732 might really have been printed in 1790, long after Hogarth’s death. Furthermore, Boydell printed the plates on laid paper given to him by Hogarth’s wife Jane, as well as on a newer type of paper known as wove (Donihue). This can make dating quite complicated, as the use of laid paper might still mean that Boydell printed it, and not Hogarth. Some of our prints are also trimmed and mounted, making it hard to distinguish paper at all. In situations like that, caveats in catalog records really do work wonders.

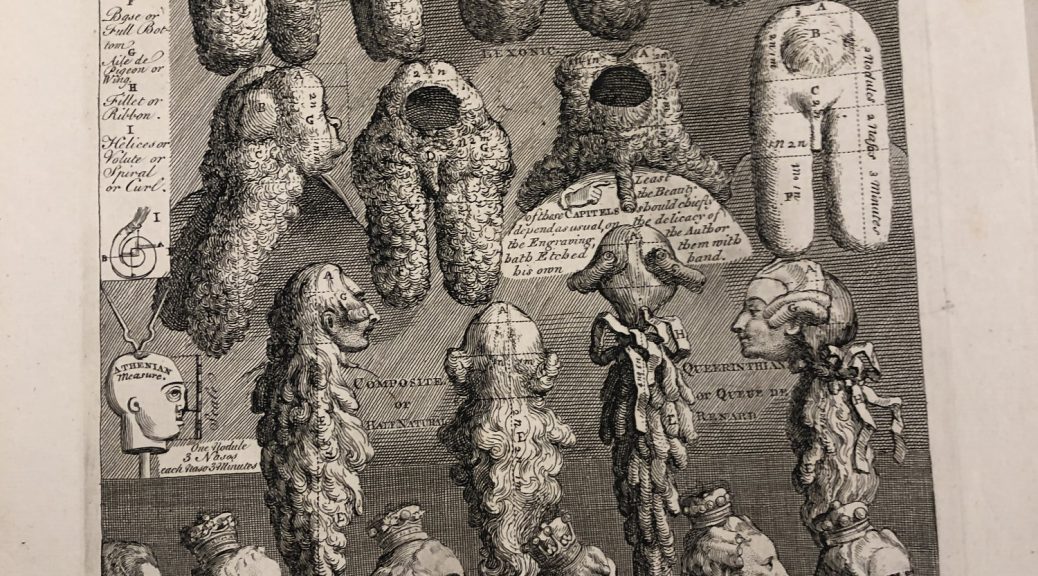

This all leads me to 2020. The future that seemed far away is our present. Our once uncataloged volume of 83 Hogarth prints is now very much cataloged. You too can see what comes of industry and idleness (spoiler: basically what you’d expect) and what wigs looked like in the 18th century (elaborate and itchy). Happy new year, new decade, and new researching to you all!

These prints were a gift acquired as part of the Frank Baker Collection of Wesleyana and British Methodism.

Citations

Donihue, David. “Boydell Editions.” In Development: William Hogarth Prints: Boydell Editions, 17 Mar. 2005, http://www.greatcaricatures.com/articles_galleries/hogarth/html/editions/ed_boydell.html.