There are many “firsts” in the Lisa Unger Baskin collection, and this early work is one of my favorites. It is one of the first books we know to be typeset by women.

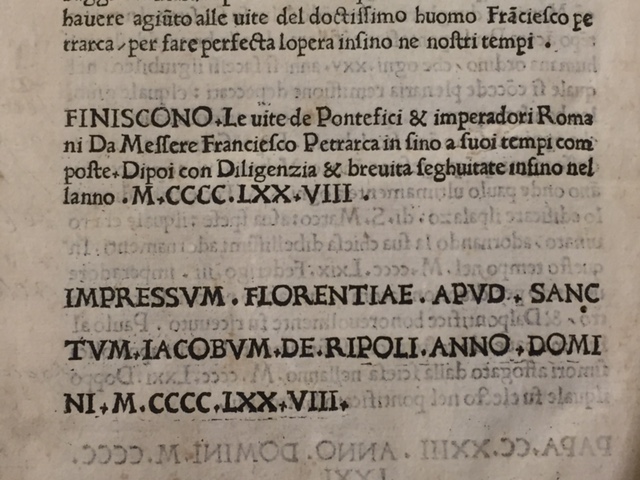

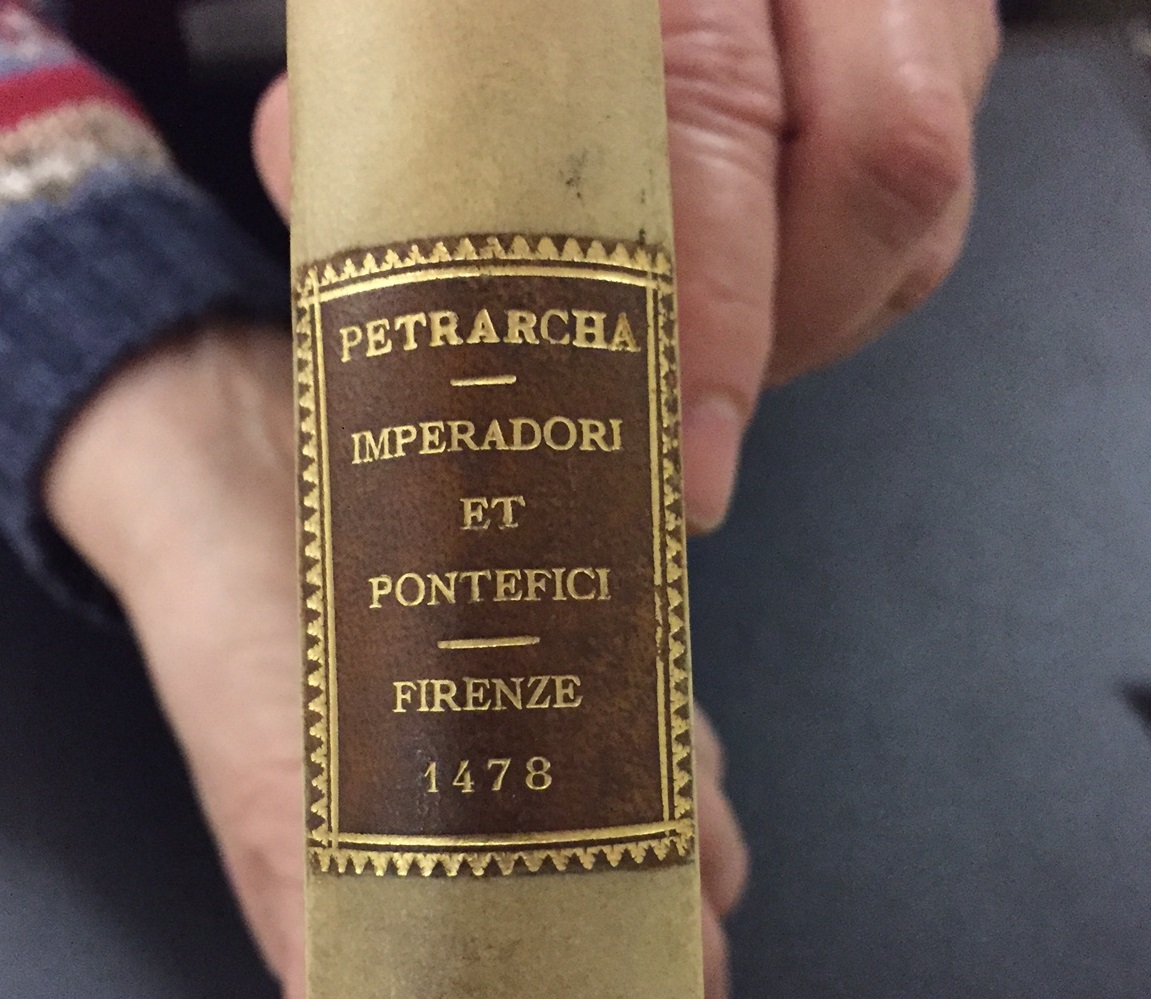

Incominciano Le uite de Pontefici et imperadori Romani [Lives of the Popes and Roman Emperors] was published by the press at the Convent of San Jacopo Di Ripoli in Florence in 1478. The Baskin Collection includes two copies. They are incunabula [cradle books], a term traditionally used to indicate works that were printed before 1501, when printing technology was still in its infancy.

Over the course of nine years (1476-1484), the Ripoli press issued around one hundred different titles, half of which were secular. The convent’s diario (daybook) notes that the Dominican sisters received modest wages for their labor, which were contributed to a common fund to support the convent.

The nuns work as typesetters was in keeping with the order’s rules. The Dominican constitutions directed the nuns to copy manuscripts for religious use, and the new technology of typesetting accomplished the same end. I have to wonder what it was like for them to literally retool with this new technology.

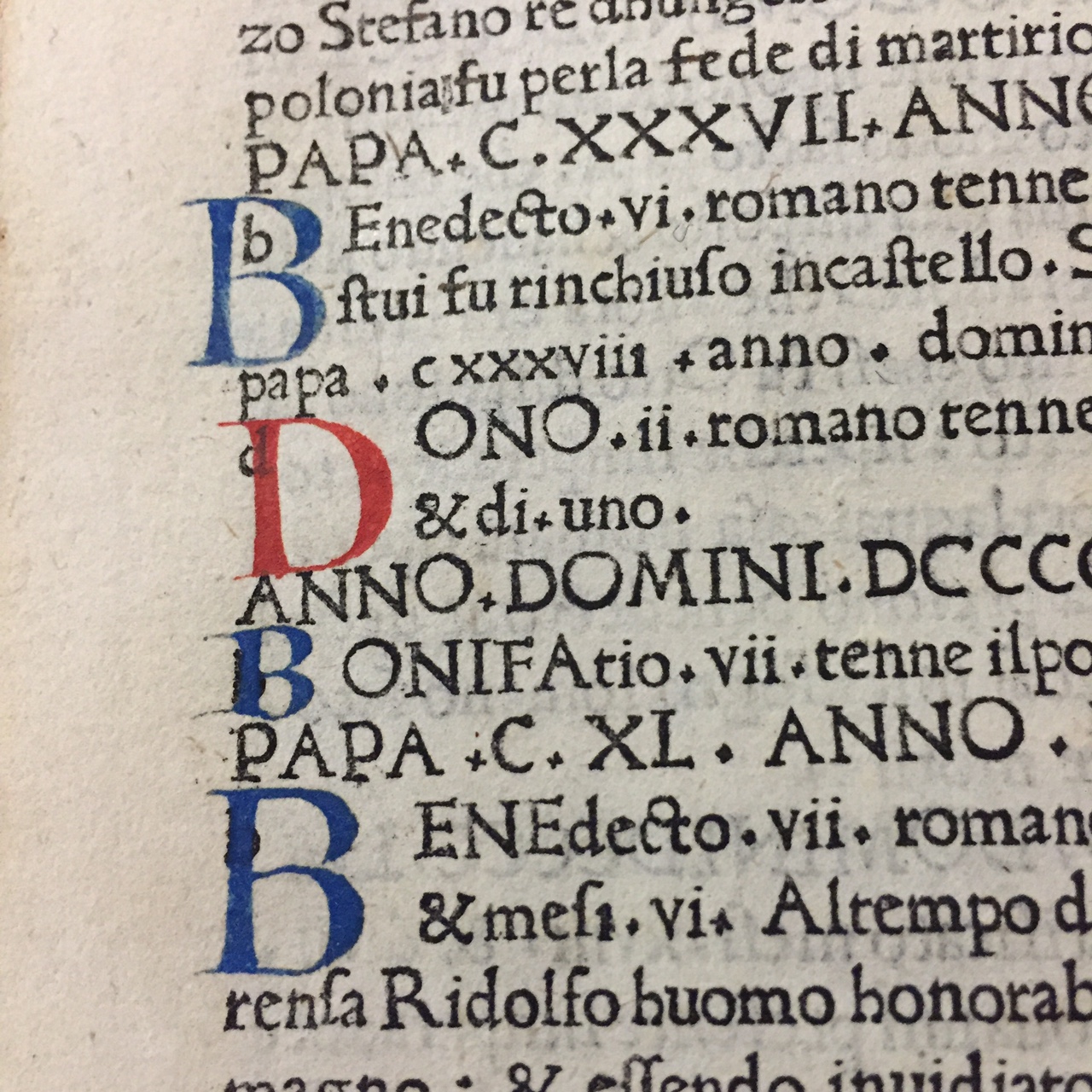

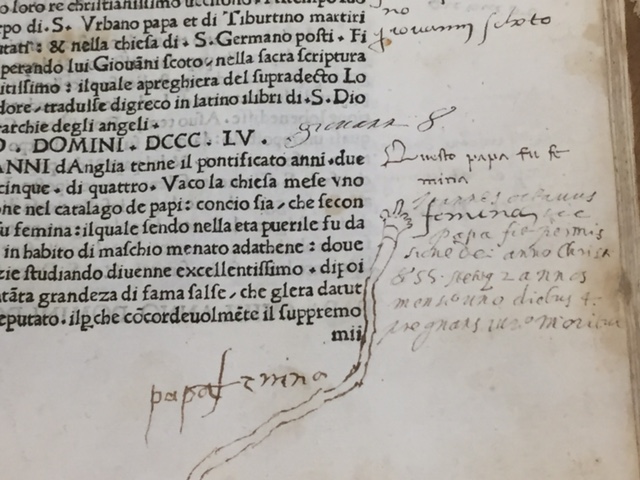

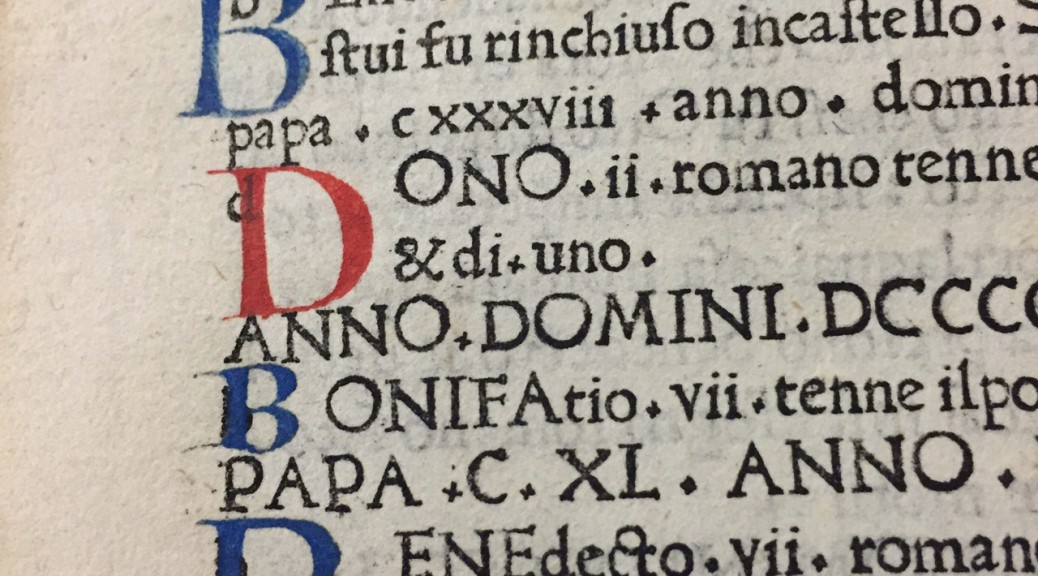

The first copy in the Baskin Collection is complete and is decorated with hand-colored initials called rubrication. Copy two lacks the first six leaves and has not yet had the decorative initials added. It is untrimmed, and over the years comments have been added in several hands and inks. Most interesting is the extensive marginalia around the entry for the (most likely) fictional Pope Joan with its long manicule and notation “papa femina.”

I look forward to sharing these volumes with students and visitors. If you run your fingers gently over the pages, you can feel the impressions made by the thousands of pieces of moveable type the nuns of Ripoli carefully set by hand.

To learn more about the work of the Convent of San Jacopo Di Ripoli consult:

- Melissa Conway, The Diario of the printing press of San Jacopo di Ripoli : 1476-1484 : commentary and transcription, Firenze : L.S. Olschki, 1999.

- Helen M. Latham, Dominican Nuns and the Book Arts in Renaissance Florence: the Convent of San Jacopo di Ripoli, 1224-1633 (Italy), dissertation, Texas Woman’s University (1986).

Post contributed by Naomi Nelson, Ph.D., Associate University Librarian and Director, Rubenstein Library.

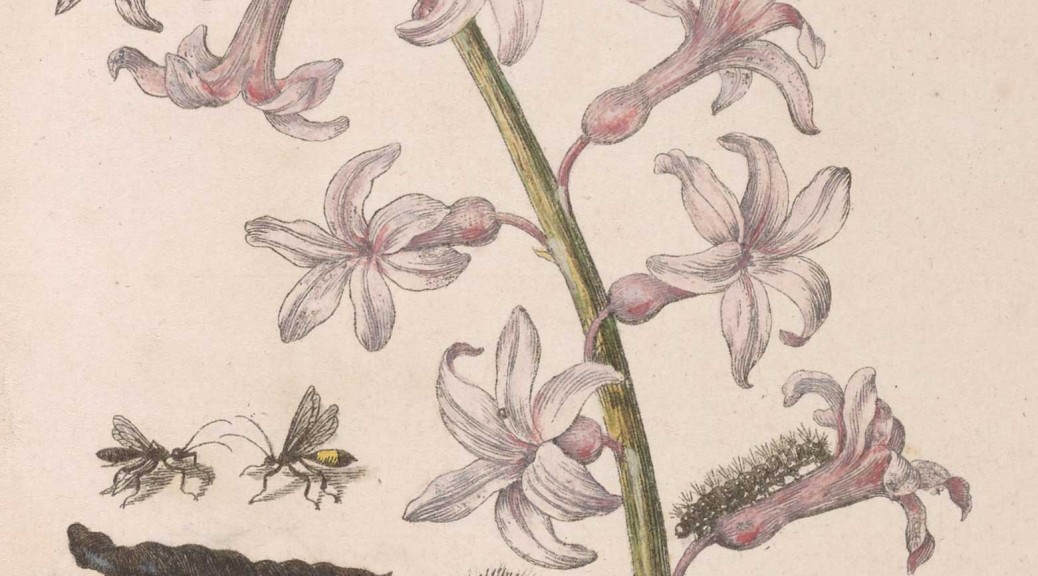

This beautiful copy of

This beautiful copy of

![Maria Sibylla Merian. De europische insecten. Tot Amsterdam: by J.F. Bernard, [1730].](https://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2016/01/merian.jpg)