So far this academic year, Rubenstein librarians have taught 132 class sessions (though we won’t finalize these numbers until the end of the spring semester). You’d think that’d be enough to fill our time, but we’ve also been meeting monthly to discuss our individual teaching practices and how to improve our students’ experiences in our class sessions. We want to inspire confident special collections researchers for life!

Through our discussions, we realized that we often returned to couple of key points about archives and primary source research in our class sessions. We’d broach those points on an ad hoc basis as they arose in classes, but we wondered if starting our class sessions off with a shared understanding of those points would be useful, reassuring, and perhaps even empowering for our students.

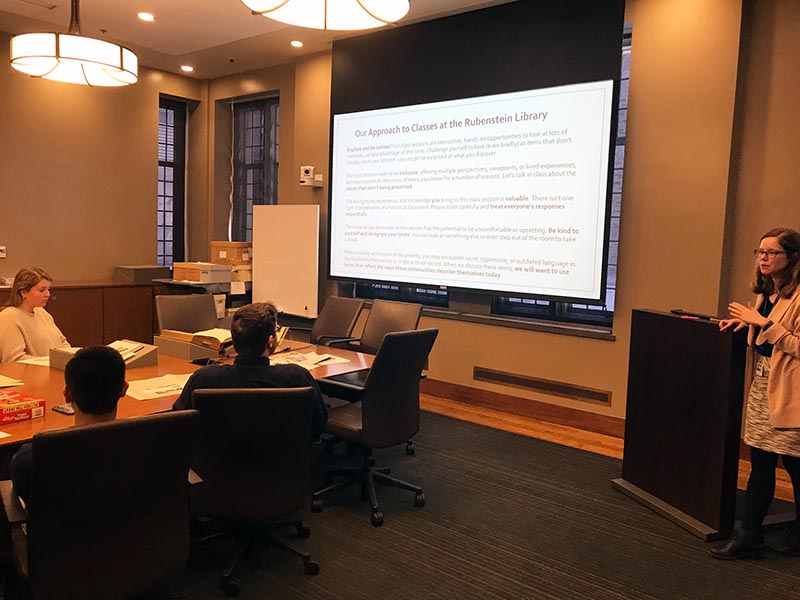

We’ve followed the development of codes of ethics for different spaces and organizations within (and beyond) our profession and thought that model might also work for us. Early this semester, we drafted and began implementing what we’re calling our approach to classes at the Rubenstein Library. (“Code of ethics” seemed so heady that it might have the unfortunate effect of tamping down student engagement.) Here is what we developed:

Explore and be curious! Our class sessions are interactive, hands-on opportunities to look at lots of materials, so take advantage of this time. Challenge yourself to look (even briefly) at items that don’t initially catch your interest—you might be surprised at what you discover.

Our class sessions seek to be inclusive, offering multiple perspectives, viewpoints, or lived experiences, but may not include the voices of every population for a number of reasons. Let’s talk in class about the voices that aren’t being presented.

The background, experience, and knowledge you bring to this class session are valuable. There isn’t one right interpretation of a historical document. Please listen carefully and treat everyone’s responses respectfully.

The material you encounter in this session has the potential to be uncomfortable or upsetting. Be kind to yourself and recognize your limits. You can look at something else or even step out of the room to take a break.

When working with historical documents, you may encounter racist, oppressive, or outdated language in the documents themselves or in the archival record. When we discuss these items, we will want to use terms that reflect the ways these communities describe themselves today.

Later this month, we’ll come together as a group of instructors to talk about how we’ve been able to incorporate the code into our class sessions—but informal reports suggest it’s been useful! Our practice has generally been to give students two to three minutes to individually read over the code (presented on a slide) and then talk as a class about any questions they might have and how the individual points in the code might come up in the class session.

We see this as a living document that we’ll continue to refine and add to as needed. So please do let us know what you think and feel free to borrow or adapt our instruction code of ethics for your own class sessions!