This post is contributed by Paula Jeannet, Visual Materials Processing Archivist, and is part of “An Instant Out of Time: Photography a the Rubenstein Library” blog series.

My work as a photographic archivist often includes improving the housing of the thousands of photographs found in older collections in the Rubenstein Library. One such group of seventy-eight photographs was recently discovered in the Isabelle Perkinson Williamson Papers, a collection of letters chiefly between Isabelle and her mother. The Perkinsons were residents of Charlottesville, Virginia, where several family members served on the faculty at the University. Isabelle married a civil engineer, Lee H. Williamson, in 1917 and traveled and lived abroad with her husband. World War I found Lee Williamson serving in the 55th Engineers of the American Expeditionary Forces in France. The collection includes his military ID card as well as some wartime correspondence.

As I sorted and sleeved the bundle of photographs, I came across a single studio portrait of three children that didn’t seem to fit in with the others, chiefly because of the children’s dress:

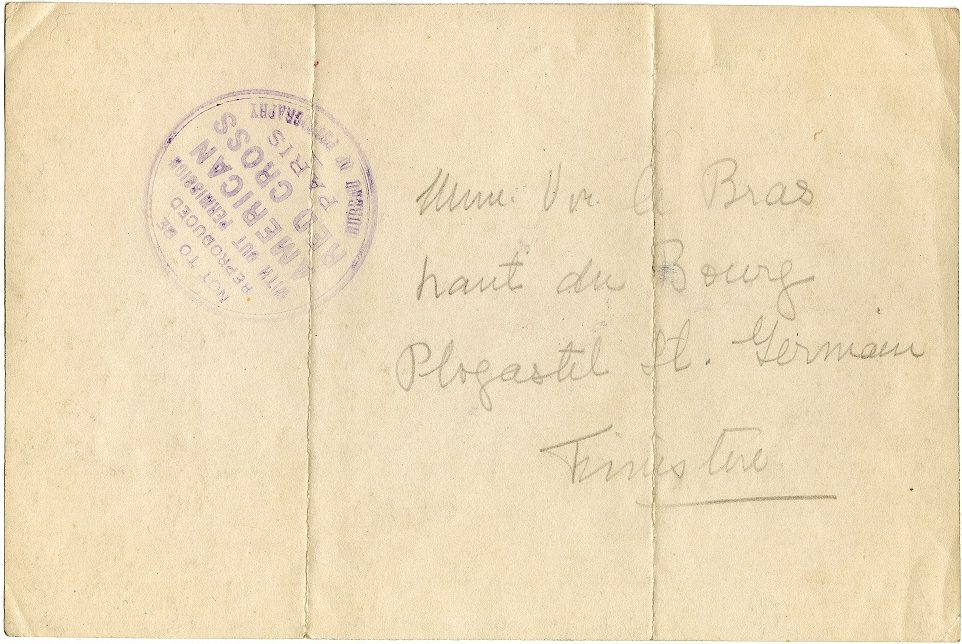

Turning it over, I observed a stamp from the Red Cross Bureau of Photography, and the address of a Madame Bras in France:

An online investigation using the negative number on the print and key words such as “Red Cross photographs” quickly turned up a matching digitized glass plate negative, part of the Library of Congress’s American Red Cross negative collection of over 19,000 scanned images.

The caption reads: “Jeanne Le Bras, adopte. Address: Mme. LeBras, Haut du Bourg Plogastel St. Germaine (Finistere Pres Guimper) protégé of: 302 Ambulance Co. Sanitary Train, Care Company Clerk. American Expeditionary Forces .” The photographer is recorded as Joseph A. Collin, who took many of the images found in the Red Cross collection.

Here’s what I learned from the Library of Congress site and other resources: in the aftermath of World War I, whose events we continue to commemorate in 2019, thousands of refugee families and orphaned children were “adopted” by American troops and cared for by American Red Cross staff. The Red Cross hired professional photographers to document the organization’s efforts in Europe; they took hundreds of portraits of refugees and orphan children. The images may have been used in many ways: to find lost families; to publicize children available for adoption, or to record their successful adoption. As an interesting sidelight, I discovered that one of these photographers was Lewis Hine; his camera recorded over 1100 images for the Red Cross and are also part of the Library of Congress collection.

Lewis Hine was a gifted portraitist, reflected in his work for the Red Cross.

Some of the images in the Library of Congress Red Cross collection show signs of heavy editing: children were erased from group portraits, perhaps because they had already been adopted, and in some cases, adult figures blocked out. The latter was a common practice of the 19th century – explore this phenomenon by searching online for “hidden mothers photography.”

The Library of Congress caption for the single image found in the Rubenstein collection names only one child out of the three, Jeanne; it is not clear which one was Jeanne, but one hopes that all three were adopted and raised by kind families. Also a mystery is how the photograph came to live with the others in the Isabelle Williamson collection. It may have originated from Isabelle’s husband, who served in World War I, or from a friend of the family, Mary Peyton, who was a field nurse in World War I.

There is an abundance of primary source material on World War I in the Duke Libraries – images as well as papers. “Views of the Great War,” a Rubenstein Library online exhibit, is a great way to learn more about this world-changing event as revealed through our collections.

For more information on the Isabelle Williamson collection, see the collection guide.