Post contributed by Paula Jeannet, Visual Materials Processing Archivist at the Rubenstein Library

“Apart from the pulling and hauling stands what I am,

Stands amused, complacent, compassionating, idle, unitary,

Looks down, is erect, or bends an arm on an impalpable certain rest,

Looking with side-curved head curious what will come next,

Both in and out of the game and watching and wondering at it.

Backward I see in my own days where I sweated through fog with

linguists and contenders,

I have no mockings or arguments, I witness and wait.”

Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself,” Section 4

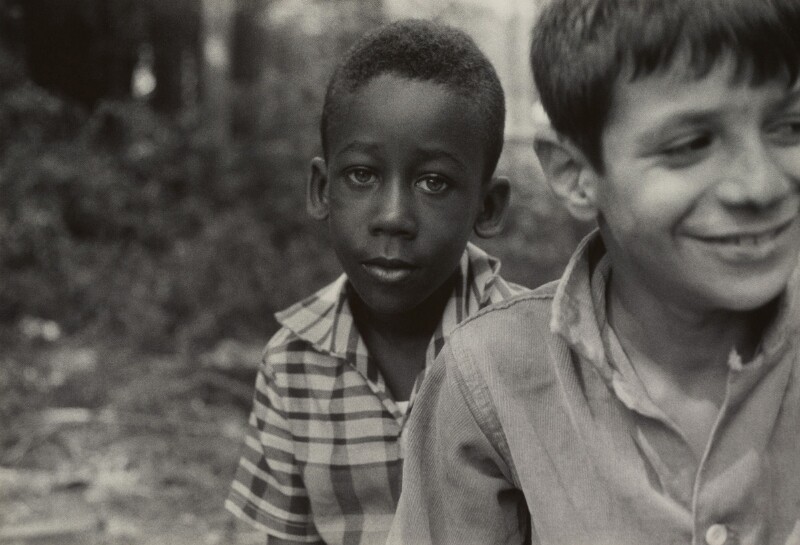

June 23, 2019 marked the 30th anniversary of photographer William Gedney’s death in New York City in 1989 at the young age of 56. Gedney’s career spanned a time of great changes in American society and elsewhere, and in his photographs he captures the vitality and promise of those decades as well as the counterweights of social isolation and poverty. A lover of literature, he found early inspiration for his work in another New Yorker: Walt Whitman. Like Whitman, Gedney was fascinated by people in all their complexity and was an exceptional portraitist, using his camera rather than a pen; like Whitman, he was especially drawn to street life and crowds. The full extent of Gedney’s preoccupation with Whitman can be more fully explored through the photographer’s archive; for now, this blog post will indicate some starting points in the collection.

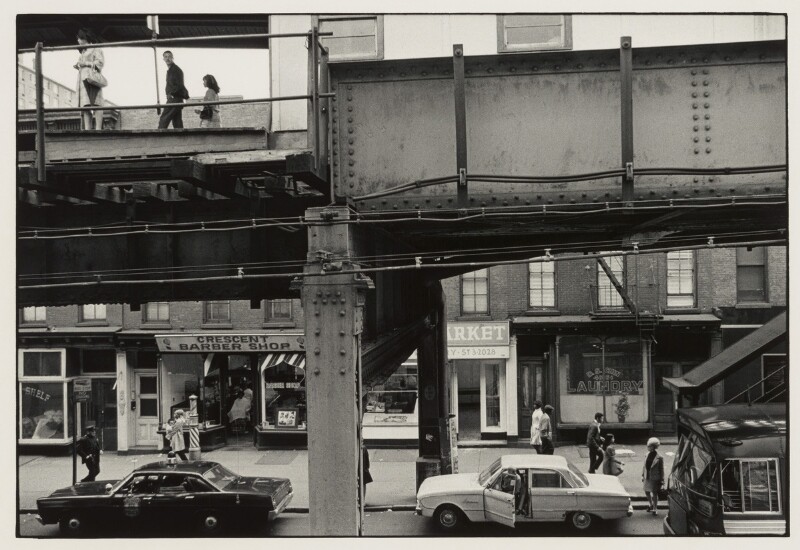

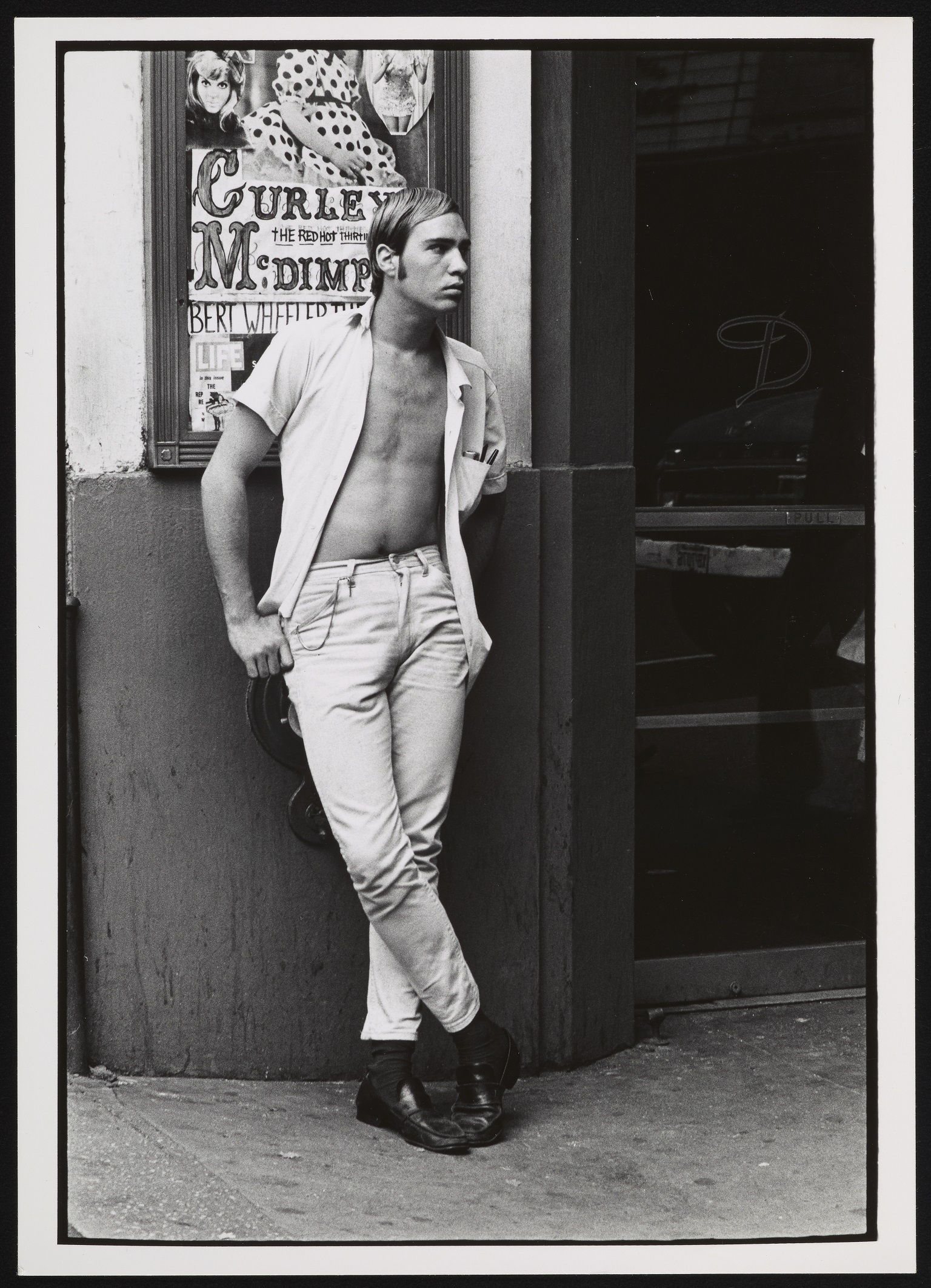

Born in 1932, Gedney grew up in rural Greenville, New York, in the Hudson River Valley. As a child, his family took him to visit relatives in the big city, and ultimately he studied art at Pratt Institute and moved into a cold-water flat in Brooklyn in the mid-1950s. While working as a commercial photographer to pay the bills and cover darkroom expenses, he roamed Brooklyn neighborhoods, his camera loaded with black-and-white film. Many of the images capture daily life and the inhabitants of Myrtle Avenue, where he lived. He continued this documentary work for the rest of his life.

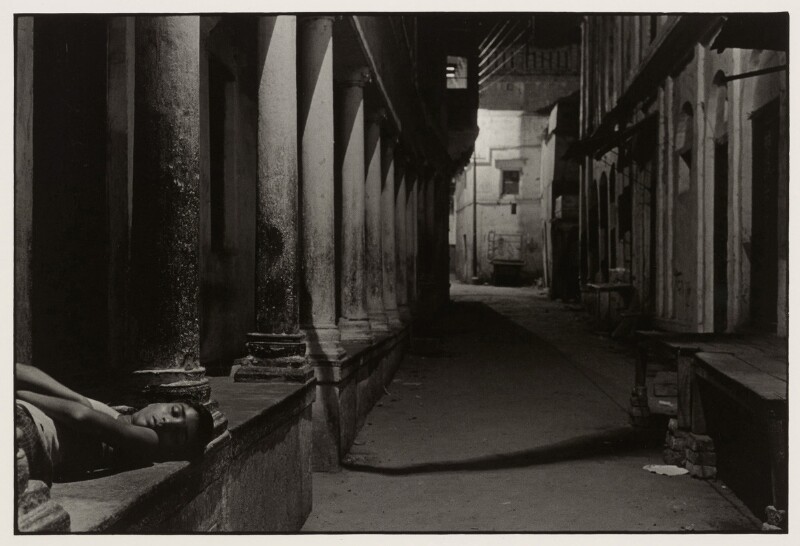

In 1966, William Gedney’s photographic life took flight: he traveled to Kentucky (twice), cross country to California (also twice), then across the ocean to Ireland, England, Paris (twice again), and India, also twice. Brooklyn always drew him back.

Sometime around 1968 or 1969, perhaps inspired by Whitman’s interest in celebrating and documenting urban street life, he began a consuming project to uncover the history of Myrtle Avenue from its beginnings in the 18th century, using newspapers and literary sources, including the Brooklyn Eagle, for which Whitman served as editor, writing copious notes and pasting clippings in two volumes, Myrtle Avenue 1 and 2 – another habit he would continue throughout his life. Some of his notes include transcripts of Whitman poems:

At some point (probably earlier than 1969), he discovered that Walt Whitman had lived in Brooklyn, on 99 Ryerson Street, just a few blocks from Gedney’s neighborhood on Myrtle Avenue. While living at that address, Whitman published his ground-breaking epic poem Leaves of Grass in June 1855.

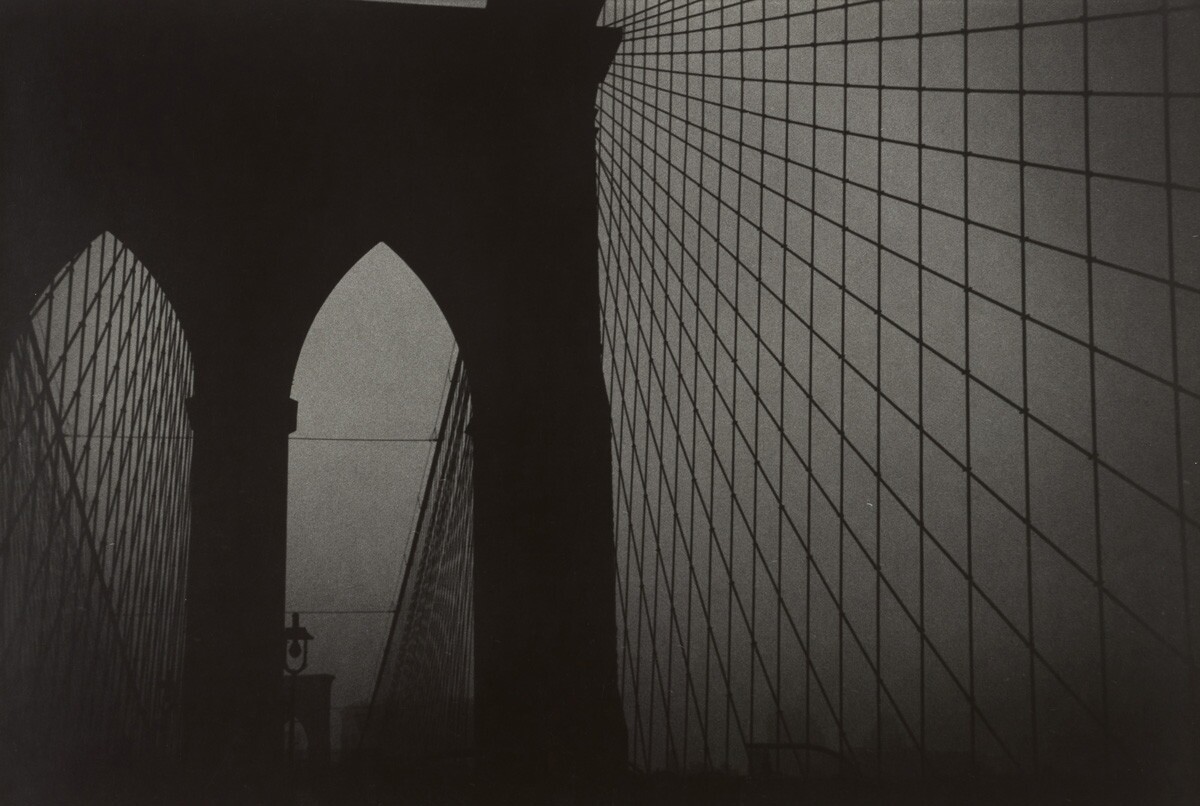

Although it’s not clear when the idea first came to him, in 1969 Gedney began to create the layout for a project to combine Whitman’s verses with his own photographs of New York City. In one of his notebooks, titled only with the year 1969, he writes about “the bridge” photographs, and of framing them with Hart Crane’s poem “The Bridge.”

A few months later, in the same notebook, Gedney writes “I think the bridge pictures would be best paired with Whitman’s Brooklyn Ferry poem under the overall title ‘Brooklyn Crossing.’ His poem is the one I was most under the influence at the time.” The Brooklyn Bridge book maquette in the Gedney archive contains no accompanying texts; however, during the recent Rubenstein project to rehouse and digitize the Gedney archive, the lead archivist came across this item hiding out in a box of oversize materials:

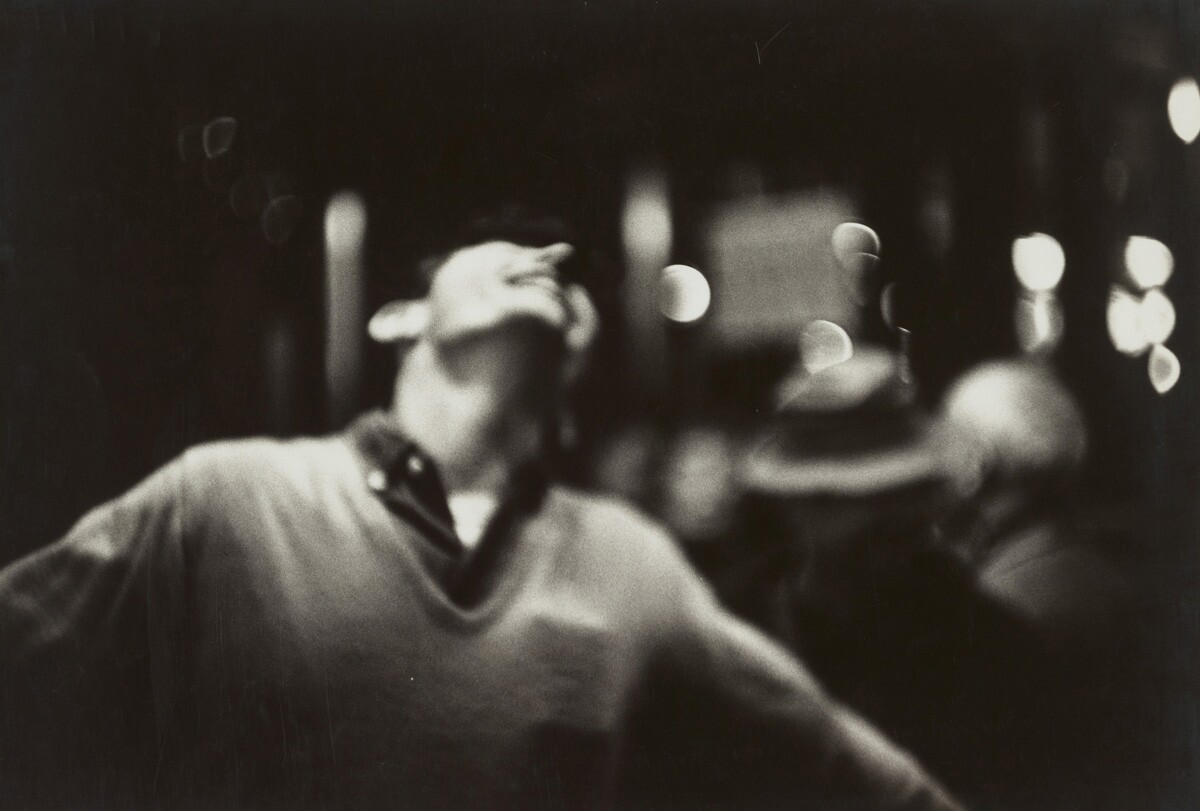

Sometime around 1970, Gedney again turned to Whitman’s verses, this time selecting the poem “I wander all night in my vision” to introduce his planned book of night photographs taken in India. Clearly Whitman was still on his mind and informing his work.

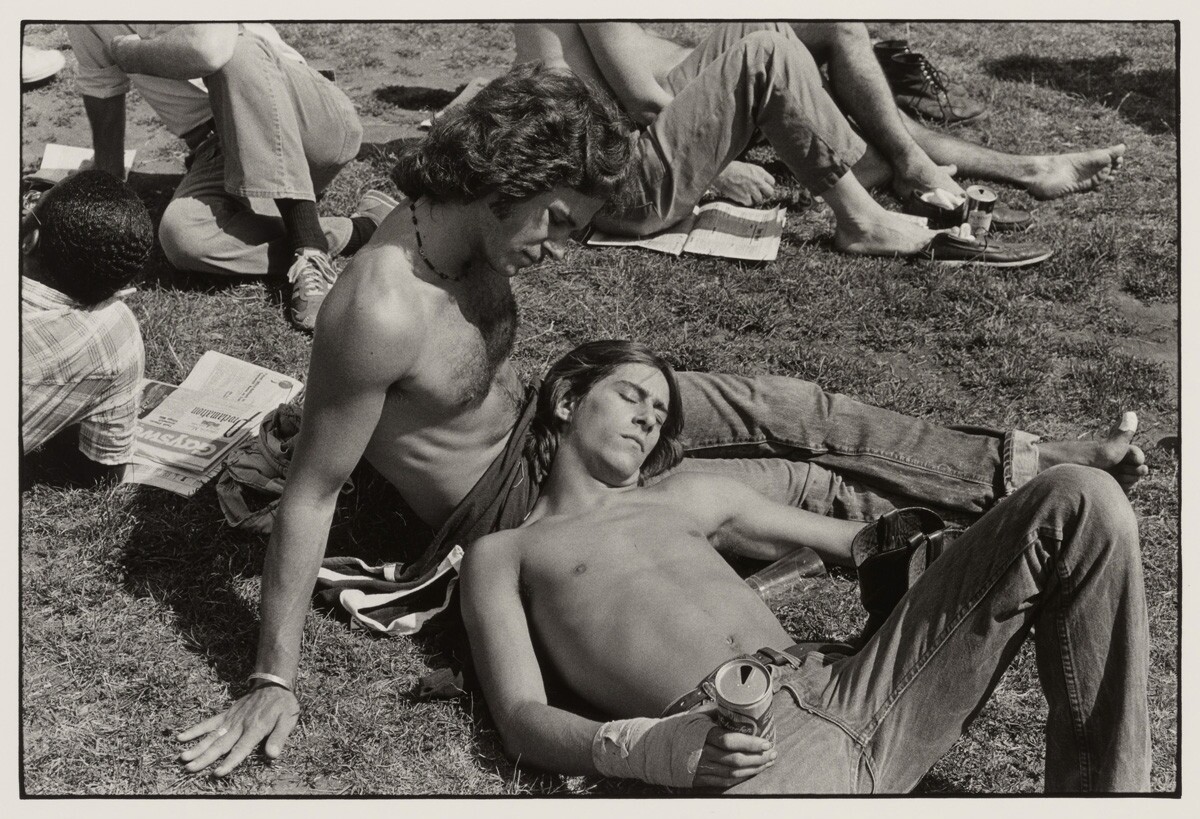

I had thought Gedney’s connection to Whitman largely remained unexamined, with the exception of Margaret Sartor’s comments in her seminal book introducing Gedney and his archive to the world: What Was True: the Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney (W.W. Norton, 2000). Then, while researching this blog post, I discovered Mark Turner’s book, Backward Glances: Cruising the Queer Streets of NY and London (Reaktion Books: London, 2003), which in the context of the phenomenon of male cruising, discusses the remarkable parallels between Gedney and Whitman. The two clearly favored male liaisons, and this orientation was reflected to some degree in their poetic and artistic work. Beginning in 1975, Gedney began extensively documenting the exuberant gay pride parades as well as street hustlers in San Francisco and New York, until a few years before his death. At the same time, he was intensely private about his personal life, never fully coming out even to his closest friends.

“…as I pass, O Manhattan! your frequent and swift flash of eyes offering me love,

Offering me the response of my own–these repay me,

Lovers, continual lovers, only repay me.”

Walt Whitman, “Calamus 18”

Like William Gedney, Walt Whitman also celebrates an anniversary in 2019: he was born 200 years ago on May 31, 1819. Many events have been planned in his honor: http://waltwhitmaninitiative.org/

It’s easy to imagine that he would have been intrigued by Gedney’s photography and pleased at the idea of a publication of Brooklyn images prefaced by his own verses.

Sadly, it was not to be: Gedney bequeathed the world a body of compelling, eloquent photographic work, but his many book projects remained unpublished, with only the book maquettes in the archive as evidence of Gedney’s hopeful plans. Perhaps with the right editor, these two artists will be joined again as Gedney had imagined.

“These and all else were to me the same as they are to you,

I loved well those cities, loved well the stately and rapid river,

The men and women I saw were all near to me,

Others the same—others who look back on me because I look’d forward to them,

(The time will come, though I stop here to-day and to-night.)”

Walt Whitman, “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” stanza 4

Note about the Gedney Collection: Although William Gedney’s work was still largely undiscovered by mainstream audiences at the time of his death in 1989, it stood on the cusp of an awakening, thanks primarily to the efforts of close friends Maria and Lee Friedlander, and John Sarkowski, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art. Eventually the entire Gedney archive — over 49,000 photographs, negatives, artwork, and papers – came to Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, and is now being digitized in its entirety (the finished prints and contact sheets are already available online). You can learn more about the collection by visiting the collection guide online.

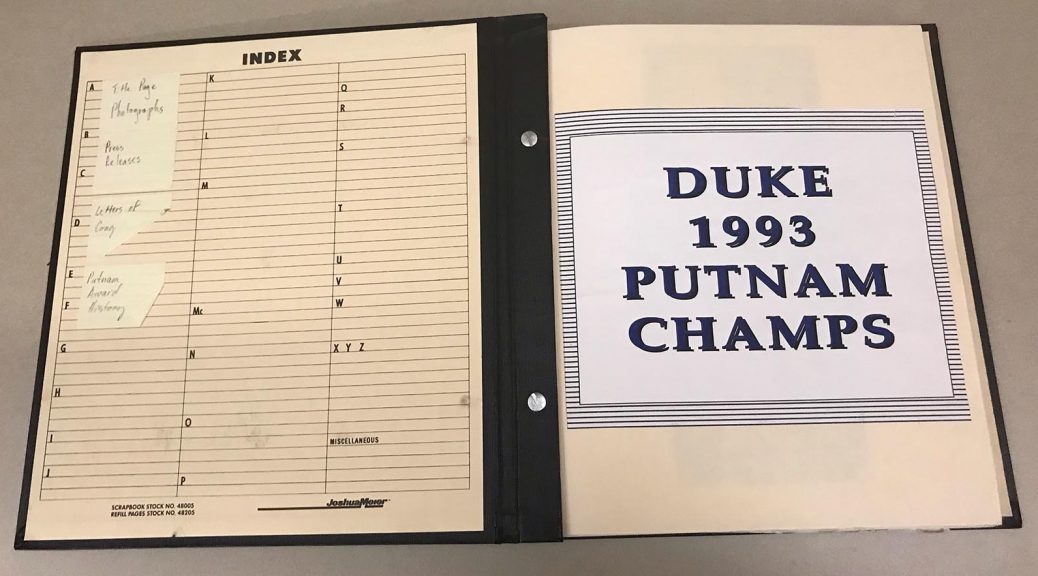

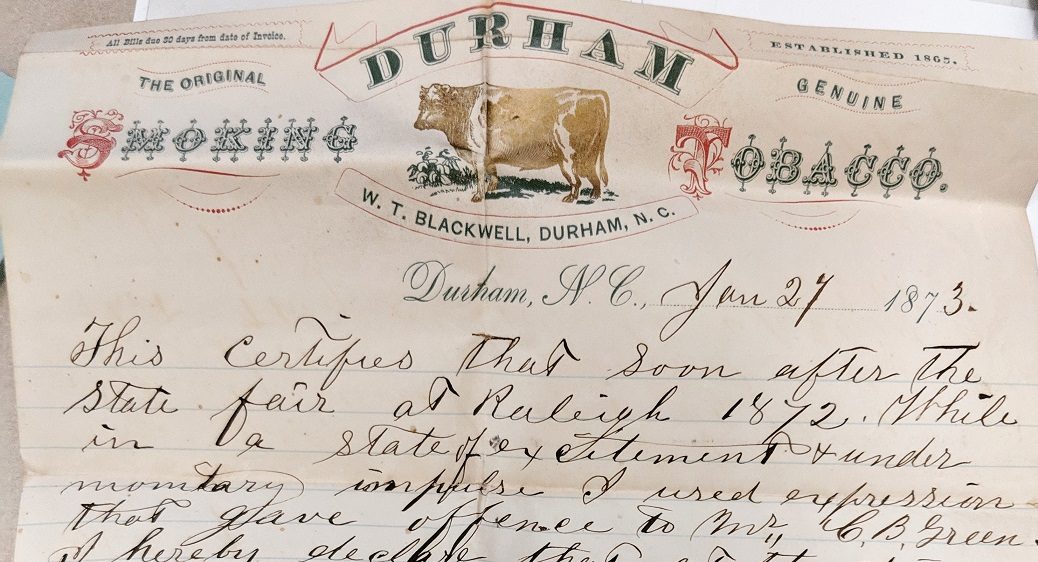

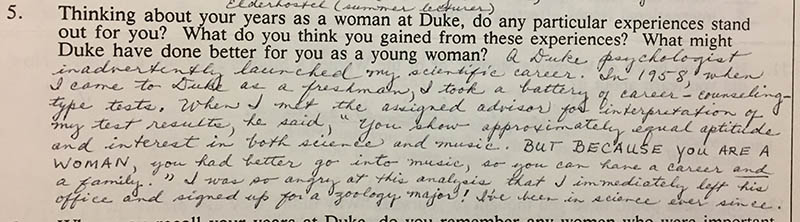

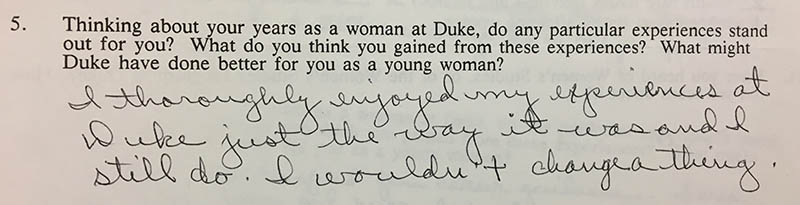

![Question 5: “Thinking about your years as a woman at Duke, do any particular experiences stand out for you? What do you think you gained from these experiences? What might Duke have done better for you as a young woman?” Answer: “I was lucky to have lived in Epworth for two years where many strong-willed, energetic, creative women students served as role models and challenged me. (I was VP one semester and Pres. another.) They gave me courage. I dropped my math major my sophomore year – was told by my math prof. (a young-ish male – [name redacted]) that women usually don’t make it as mathematicians because they are not aggressive enough. By the end of my soph. year, there was only one other woman besides myself in my math class. I get angry every time I think about the chilling effect this prof. had on my – I sincerely hope that he’s no longer teaching at Duke.”](http://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2019/06/1977_Q5_1.jpg)