Every other year, the Duke University Libraries survey our patrons to learn more about their opinions about library spaces, services, and materials. Our biennial satisfaction survey for 2020 targeted our student patrons (both undergraduate and graduate) and covered topics from navigation of our buildings to website features to access to electronic materials.

Earlier this year, the survey was sent to a sample of 4,000 of our undergraduate and graduate students and was also linked from the library homepage for other students to complete. Almost 2,800 students participated in the survey, about half of whom were undergraduates (spread fairly evenly across all four years of study, except for an overrepresentation of first-year students).

While we will spend several more months reviewing the results and identifying opportunities to improve our services, we have completed our initial analysis of both the fixed choice and free text questions. The following high-level takeaways represent the major themes that emerged across the survey responses.

- Students feel safe and welcome in our libraries.

- Students cherish the support from library and security staff.

- Our Top Textbook initiative has had a huge impact on students.

- We need better communication of our norms and enforcement of our policies.

- Individuals and small groups have trouble locating private places to work.

- Students want better lighting and access to greenery and outdoor spaces.

1. Students feel safe and welcome in our libraries.

This year, we asked students how much they agree with the following statement: “I feel safe from discrimination, harassment, and emotional and physical harm at… Duke University/Duke Libraries.”

The results show that for Duke University, 90% of students at least somewhat agree. For Duke Libraries, 95% of students at least somewhat agree with the statement, and 83% strongly agree. (Note: we asked a similar question in 2018 and saw a similar pattern, but the results aren’t directly comparable because we changed question and the response options.)

Another way we measure how students feel about the library is to ask about their agreement with an additional statement: “For me, the library is a welcoming place.”

Student agreement with this statement was quite high, especially among international and graduate students.

A quote from a response to one of our free-text questions nicely captures some of these reflections from students:

“I generally feel safe and included at the Duke libraries – I particularly like the diverse/inclusive the art installations in the front entrance and at the back of the first floor. These make me feel more included and I wish there were more of them!”

Duke Libraries’ response to this finding:

2. Students cherish the support from library and security staff.

Our survey didn’t specifically ask students if they are satisfied with library staff. This message, however, came through loud and clear in our qualitative comments.

After asking students about whether they feel safe at Duke and at Duke Libraries, we offered them the opportunity to explain with a free-text question (“Please describe your response and your experience with the Duke University Libraries in this context.”). Of the 260 responses to this question that mentioned library staff, 246 responses (or 95%) were compliments of the staff.

“I appreciate that the Duke Librarians, more than anyone else, go out of their way to make visible their commitment to allyship and inclusivity.”

“Duke libraries staff are extremely kind and caring. They have not judged me for who I am or what I need help with.”

“Everyone I’ve interacted with at the Library has been absolutely wonderful – from folks at the reference desk to the Center for Data and Visualization Sciences staff.”

Other questions were phrased to encourage critiques or requests, but even those questions included staff compliments.

“Keep hiring helpful and kind staff.”

“Great staff! I’ve always found everyone at Duke Libraries very friendly and helpful whenever I run into a library problem I can’t figure out.”

Our Libraries have several groups of staff that interact directly and regularly with our students. We were delighted to see that an important part of our staff family, the security guards, were complimented very explicitly by survey participants.

“The ample lighting and security presence makes me feel that I can be at Duke even when it is late.”

“I feel very safe at the Library knowing that there is always a guard making his/her way around the library and looking out for students. It has been one of my favorite places to work in the University.”

Duke Libraries’ response to this finding:

- Began work on improvements to security guard training to emphasize the impact of smiling and greetings on student feelings of safety and welcome

- Provided optional buttons to all staff: pronouns, the trans flag and the LGBTQ flag with the DUL reading devil overlay

- Encouraged staff to attend Ally/PRIDE trainings and then display their certifications on their staff directory pages

- Shared DUL User Service Philosophy with all new DUL staff and students

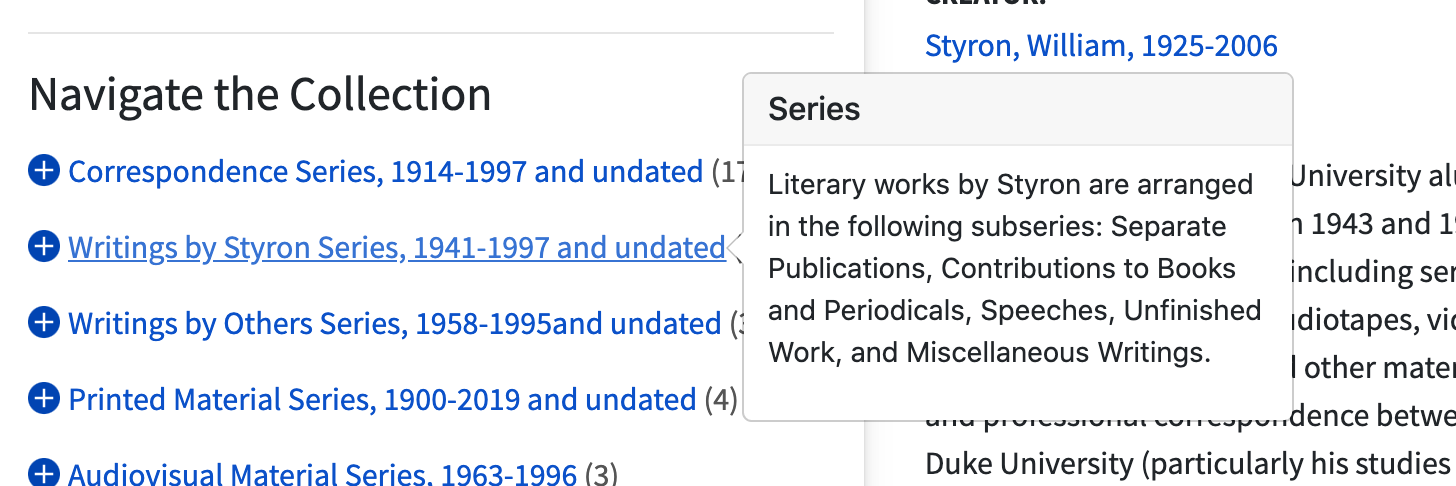

3. Our Top Textbook initiative has had a huge impact on students.

The Libraries currently make textbooks available for short-term loan for the top 100 courses each semester (by enrollment). When asked about services that are important to them, 39% of undergraduates* list this “Top Textbooks” program as important, which means the service ranks right below core library services like ePrint, reservable rooms, and drop-in assistance at a service desk.

“I often take out textbooks for classes on reserve, have taken out a few books, and often study there.”

Furthermore, perhaps thanks to increased marketing efforts following our 2018 survey, only 7% of undergraduates report that they are unaware of the service. About 52% of undergraduates have given some response about how well it meets their needs, suggesting they have some experience using the service.

While this program seems to have had success for outreach and use, students still have some unmet needs in this area. When we ask about the services we should be expanding, just over 50% of undergraduates report that expansions to the textbook program would improve their experience a lot.

“Have more copies of textbooks (I really do enjoy the ones they do have – thanks!!).”

“In a perfect world, the Library [would have] multiple copies of most of the textbooks used by professors. While the inventory of books is huge, the library is missing the ones we actually use in the Econ department.”

* – Note: this question was only shown to students who selected our main West and East Campus libraries as their primary libraries, which comprises only about 92% of undergraduates who identified a primary library.

Duke Libraries’ response to this finding:

- Increased outreach around this program by targeting faculty teaching supported courses and asking them to advertise program in syllabi

- Increased physical signage about program around library buildings

- Note: result of marketing efforts was 150% increase in use of program between spring 2019 and fall 2019

4. We need better communication of our norms and enforcement of our policies.

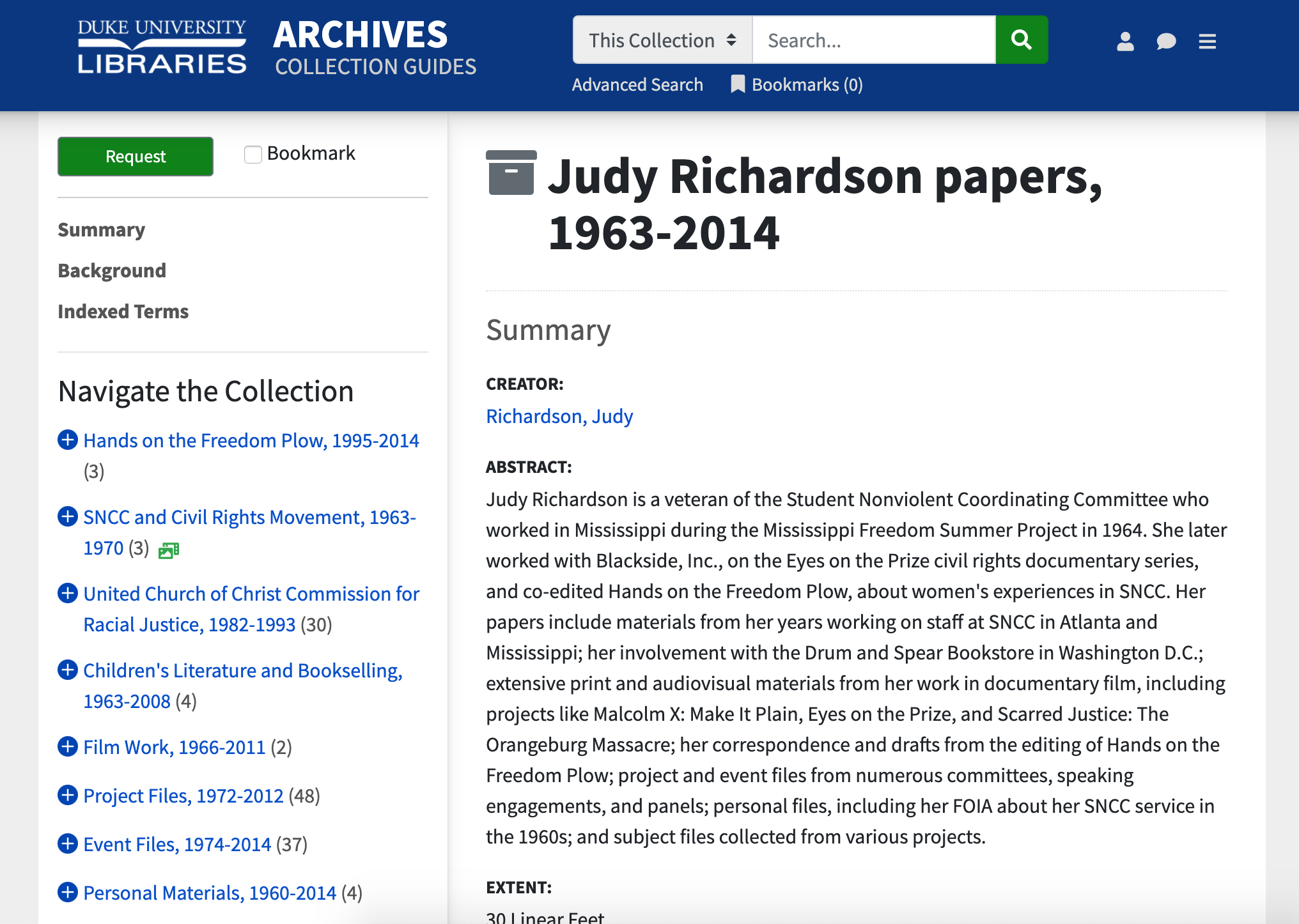

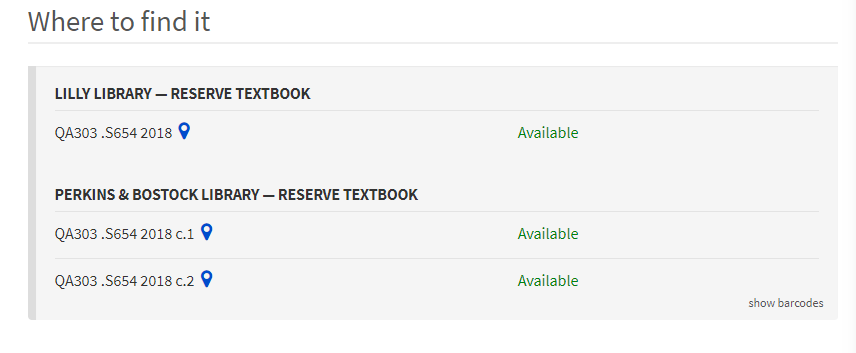

Unfortunately, students do also experience frustrations in our spaces. One example is the navigation of our spaces, especially the three connected West Campus libraries: Rubenstein, Perkins, and Bostock. On this survey, we asked if students feel confident locating a print book in the library. This question received the second lowest average agreement score of the options presented, for both undergraduates and graduates. Overall, about 23% of students lack confidence in their ability to locate a print book.

As you might expect when a large group of people shares a limited resource, students often struggle to negotiate the use of our study spaces. One area of great importance for effective studying is noise level. Some prefer absolute quiet, some prefer a low-level murmur, and others need to be able to converse freely with friends and project teammates. The Libraries have established noise norms for the various study zones in our libraries, but survey comments suggest that these norms are unclear or not always followed.

“[The Libraries should] separate talking zone and quiet zone more precisely. Someone may chat in considerate quiet zone for a long time, which is annoying.”

Furthermore, over the course of the last few years, we have seen a growth in reports of social groups that “take over” spaces and violate, especially, the noise norms of those spaces. While this stresses already taxed resources by using up seats in study spaces for social activities, it is also regularly mentioned as behavior that harms the welcoming and inclusive atmosphere of the library.

“Do away with the ‘assigned’ seating based on group membership!”

“I feel like groups of people frequent the library and there is no space for inclusion or initiatives to get people going to the library that look like me.”

“I don’t know how this would be done, but I would feel more comfortable in the libraries if undergraduate students didn’t claim and allocate spaces for themselves according to their social groups. As a graduate student of color, I don’t feel comfortable in those spaces.

“I think having the library as ‘satellite sections’ for some Greek organizations can make the library feel daunting. If there is a way to do away with this that would be great.”

Duke Libraries’ response to this finding:

Along with the previously mentioned diversity and inclusion activities, the Libraries are exploring ways of improving the communication of norms and enforcing policies.

- Began working with Dean of Students Sue Wasiolek and other Student Affairs administrators to address the issues students experience in the Libraries

- Developed and distributed new signage around finding books in the library, including instructions about how to read a Library of Congress call number

- Initiated a redesign of our noise norm signage

- Proposed new furniture arrangements for large, quiet study spaces that discourage conversation and group congregation

- Began work on improvements to security guard training to empower them to identify and address policy violations and promote a more inclusive environment

5. Individuals and small groups have trouble locating private places to work.

Identifying the best furniture for different study spaces is a constant challenge. On this survey, we asked students about expanded services that improve their experience of the library. Out of 18 options covering furniture, spaces, and other services, the top request for both undergraduate and graduate students was individual desks, with 64% of students responding that they would improve the library experience “a lot.”

“I think some more individual study spaces would be very welcome. I prefer to work on the fourth floor because the desks with dividers are very useful in separating you from others so that you can concentrate on your work and not be bothered by anyone. There are few spaces like this, except for study rooms. Perhaps some more desks with dividers or separate spaces for individual work can help people to have a safe space where they will be free from others attempting to make them feel unsafe.”

Some students report frustration that resources like individual desks aren’t always being used as efficiently as possible. While the Libraries have a policy that belongings should not be used to “reserve” a study space for longer than 15 minutes, this policy is difficult to enforce, leading to spaces that are unusable for long periods of time.

“More individual study rooms and carrels. More seating in general. Somehow stop people from reserving carrels and tables by leaving their belongings there while being away for long periods of time. (Sometimes I am looking for an individual place to sit and it seems like half of the carrels have just belongings left there.) The reservable study rooms seem to all get booked quickly during the finals period, which is disappointing because they are very good to use for working on group final projects.”

Private spaces like group study rooms and interview rooms are extremely popular among students, consistently ranking in the top 5 for important services and the bottom 5 for how well services are meeting students’ needs, as well as being highly ranked among services that should be expanded. As with desk space, these resources can be informally reserved by leaving belongings in an empty room, leading to frustration when a group needing study space cannot find an empty room. Policies like limits on the amount of time a group can reserve a room and a requirement that rooms be used for group work (or interviews) attempt to make sure these rooms serve their intended purpose, but it is very difficult to enforce those policies.

Duke Libraries’ response to this finding:

- Created and improved documentation of room policies

- Began work on new signage for group study rooms to reinforce policies and empower students to push back on inappropriate usages of the spaces

- Made recommendations for new furniture purchases in line with student needs and desires

- Proposed new furniture arrangements for large, quiet study spaces that discourage conversation and group congregation

- Proposed new signage and directories throughout the library to make it easier for students to locate study spaces

- Enhanced the Find Library Spaces portal page to help students identify spaces appropriate for the type of work they need to do

6. Students want better lighting and access to greenery and outdoor spaces.

A final growing trend among students is the request for spaces that take better advantage of nature. In additional to several free-text comments that mentioned outdoor spaces, outdoor library spaces ranked second in the list of requests for expanded services.

“Incorporate more outdoor study spaces around the library and adding more areas to study with lots of windows and natural light.”

“be a space for a spectrum of socialization and quiet studying, with outdoor space and natural lighting (design for wellness)”

“More plants and green space. This is something I would love to help organize and coordinate.”

This single comment seems to capture all major trends we found in our initial analysis:

“Improve signage to reduce the chaotic feel of navigating the library, create a clearer, less confusing, and more welcoming library layout, increase rooms available for reservation for study or meetings, provide more and more comfortable quiet section seating, improve natural lighting, generally improve the library interiors to match the attractiveness of their facades, provide more printers.”

Duke Libraries’ response to this finding:

-

- Refreshed paint, lighting, and carpet in key areas of the library

- Installed new LED lights throughout the building

- Advocated for more live plants in the building

- Proposed outdoor spaces for future renovations

- Enhanced WIFI access on the patio outside Bostock Library

Next Steps

Our biennial satisfaction surveys offer a high-level view of patron satisfaction and give us a lot of actionable information. The surveys can’t answer every question, however, and often don’t provide enough detail to make specific recommendations. Our complete assessment program elaborates on these results with in-depth user studies, feedback from our student advisory boards, focus groups, and other smaller studies. Over the next two years, we will blend these results with additional data, identify and prioritize projects, and make improvements to our spaces and services.

Credit to UC Berkeley Library for the inspiration for this post.