Behind the Veil Digitization intern Sarah Waugh and Digital Collections intern Kristina Zapfe’s efforts over the past year have focused on quality control of interviews transcribed by Rev.com. This post was authored by Sarah Waugh and Kristina Zapfe.

Introduction

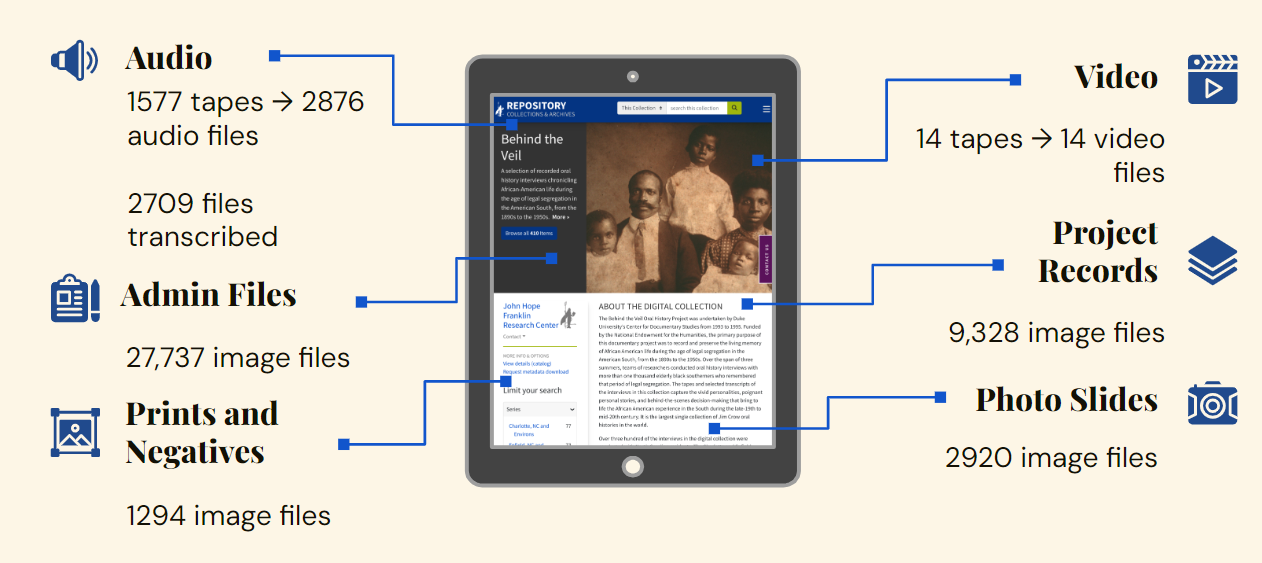

The Digital Production Center (DPC) is proud to announce that we have reached a milestone in our work on Documenting African American Life in the Jim Crow South: Digital Access to the Behind the Veil Project Archive. We have completed digitization and are over halfway through our quality control of the audio transcripts! The project, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, will expand the Behind the Veil (BTV) digital collection, currently 410 audio files, to include the newly digitized copies of the original master recordings, photographic materials, and supplementary project files.

The collection derives from Behind the Veil: Documenting African-American Life in the Jim Crow South. This was an oral history project headed by Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies from 1993 to 1995 and is currently housed in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library and curated by the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History and Culture. The BTV collection documented and preserved the memory of African Americans who lived in the South from the 1890s to the 1950s, resulting in a culturally-significant and extensive multimedia collection.

As interns, our work focused on ordering transcripts from Rev.com and performing quality control on transcripts for the digitized oral histories. July 2023 marked our arrival at the halfway point of completing the oral history transcript quality control process. At the time of writing, we’ve checked 1727 of 2876 files after a year of initial planning and hard work. With over 1,666 hours worth of audio files to complete, 3 interns and 7 student workers in the DPC contributed 849 combined hours to oral history transcript quality control so far. Because of their scope, transcription and quality control are the last pieces of the digitization puzzle before the collection moves on to be ingested and published in the Duke Digital Repository.

We are approaching the home stretch with the deadline for transcript quality control coming in December 2023, and the collection scheduled to launch in 2024. With that goal approaching, here is what we’ve completed and what remains to be done.

Digitization Progress

As the graphic above indicates, the BTV digitization project consists of many different media like audio, video, prints, negatives, slides, administrative and project related documents that tell a fuller story of this endeavor. With these formats digitized, we look forward to finishing quality control and preparing the files for handoff to members of the Digital Collections and Curation Services department for ingest, metadata application, and launch for public access in 2024. We plan to send all 2876 audio files to Rev.com service by the end of August and to perform quality control on all those transcripts by December 2023.

Developing the Transcription Quality Control Process

With 2876 files to check within 19 months, the cross-departmental BTV team developed a process to perform quality control as efficiently as possible without sacrificing accuracy, accessibility, and our commitment to our stakeholders. We made our decisions based on how we thought BTV interviewers and narrators would want their speech represented as text. Our choices in creating our quality control workflow began with Columbia University’s Oral History Transcription Style Guide and from that resource, we developed a workflow that made sense for our team and the project.

Some voices were difficult to transcribe due to issues with the original recording, such as a microphone being placed too far away from a speaker, the interference of background noise, or mistakes with the tape. Since we did not have the resources to listen to entire interviews and check for every single mistake, we developed what we called the “spot-check” process of checking these interviews. Given the BTV project’s original ethos and the history of marginalized people in archives, the team decided to prioritize making sure race-related language met our standards across every single interview.

A few decisions on standards were quick and unanimous—such as not transcribing speech phonetically. With that, we avoided pitfalls from older oral histories of African Americans, like the WPA’s famous “Slave Narratives” project, that interviewed formerly-enslaved people, but often transcribed their words in non-standard phonetic spellings. Some narrators in the BTV project who may have been familiar with the WPA transcripts specifically requested the BTV project team not to use phonetic spelling.

Other choices took more discussion: we agreed on capitalizing “Black” when describing race, but we had to decide whether to capitalize other racial terms, including “White” and antiquated designations like “Colored.” Ultimately, we decided to capitalize all racial terms (with the exception of slurs). The team did not want users to make distinctions between lower and uppercase terms if we did not choose to capitalize them all. Maintaining consistency with capitalization would provide clarity and align with BTV values of equality between all races.

Using a spot-check process where we use Rev’s find-and-replace feature to standardize our top priorities saved us time to improve the transcripts in other ways. For instance, we also try to find and correct proper nouns like street names or names of important people in our narrators’ communities, allowing users to make connections in their research. We corrected mistakes with phrases used mainly in the past or that are very specific to certain regions, such as calling a dance hall a “Piccolo joint” from an early jukebox brand name. We also listened to instances where the transcriptionist could not hear or understand a phrase and marked it as “indistinct,” so we can add in the dialogue later (assuming we are able to decipher what was said).

While we developed these methods to increase the pace of our quality control process, one of the biggest improvements came from working with Rev. If we were able to attain more accurate transcripts, our quality control process would be more efficient. Luckily, Rev’s suite of services provided us this option without straying too far from our transcription budget.

Improving Accuracy with Southern Accents Specialists

When deciding on what would be the best speech-to-text option for our project’s needs, we elected to order Transcript Services from Rev, rather than their Caption Services. This decision hinged on the fact that the Transcript Services option is their only service that allows us to request Rev transcriptionists who specialize in Southern accents. Many people who were interviewed for Behind the Veil spoke with Southern accents that varied in strength and dialect. We found that the Southern accent expertise of the specialists had a significant impact on the accuracy of the transcripts we received from Rev.

This improvement in transcript quality has made a substantial difference in the time we spend on quality control for each interview: on average, it only takes us about 48 seconds of work for every 60 seconds of audio we check. We appreciated Rev’s offering of Southern accent specialists enough that we chose that service, even though it meant that we had to then convert their text file format output to the WebVTT file format for enhanced accessibility in the Duke Digital Repository.

Optimizing Accessibility with WebVTT File Format

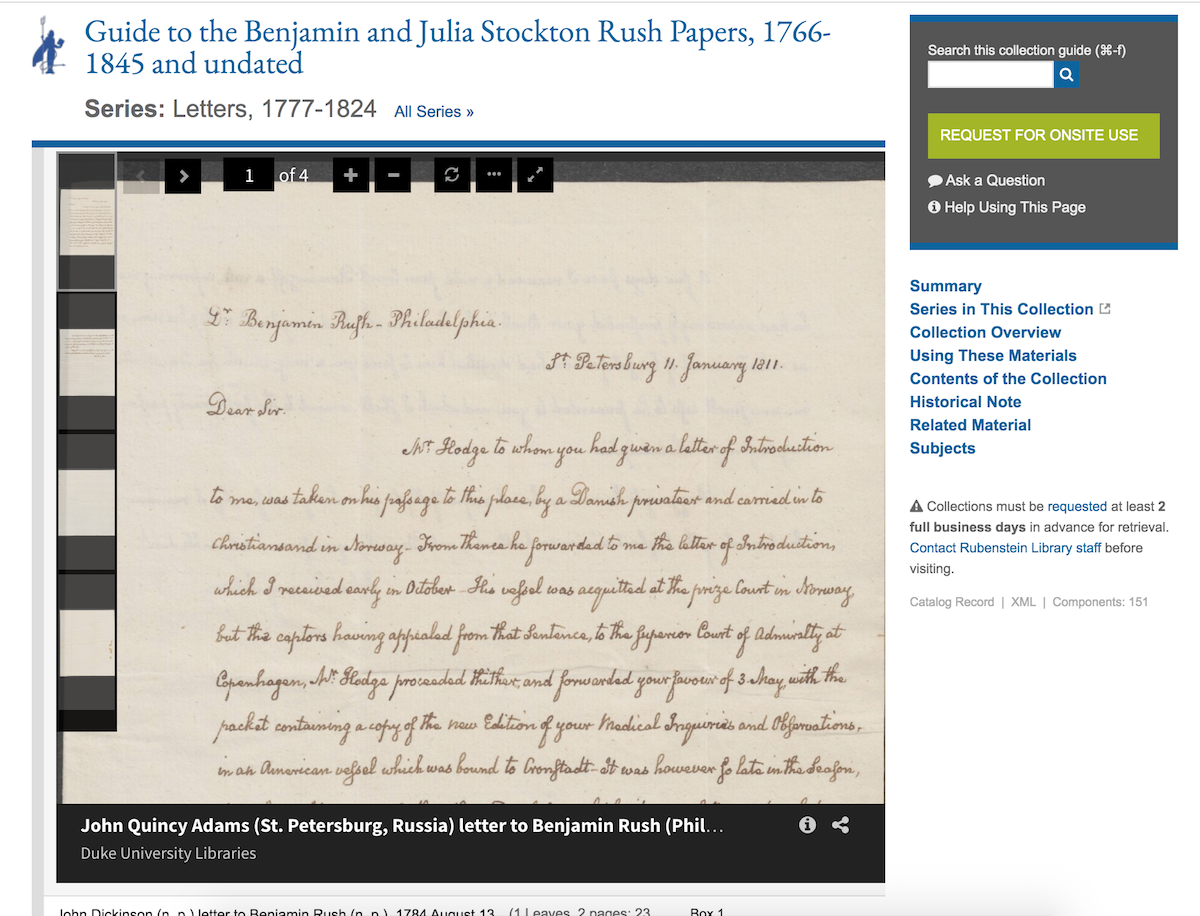

The WebVTT file format provides visual tracking that coordinates the audio with the written transcript. This improvement in user experience and accessibility justified converting the interview transcripts to WebVTT format. Below is a visual of the WebVTT format in our existing BTV collection in the DDR. Click here to listen to the audio recording.

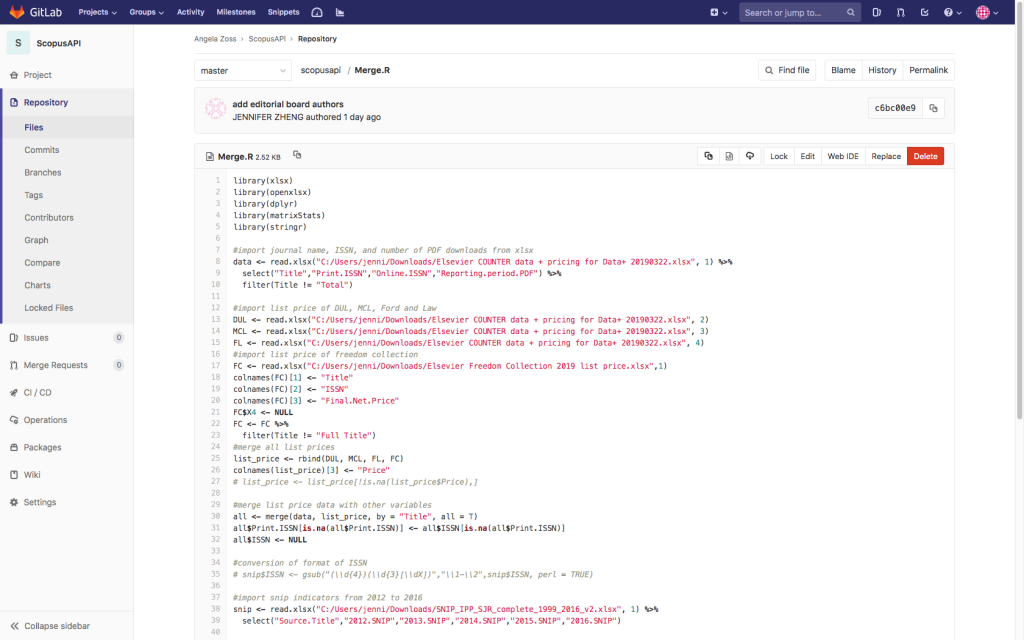

We have been collaborating with developer Sean Aery to convert transcript text files to WebVTT files so they will display properly in the Duke Digital Repository. He explained the conversion process that occurs after we hand off the transcripts in text file format.

“The .txt transcripts we received from the vendor are primarily formatted to be easy for people to read. However, they are structured well enough to be machine-readable as well. I created a script to batch-convert the files into standard WebVTT captions with long text cues. In WebVTT form, the caption files play nicely with our existing audiovisual features in the Duke Digital Repository, including an interactive transcript viewer, and PDF exports.” – Sean Aery, Digital Projects Developer, Duke University Libraries

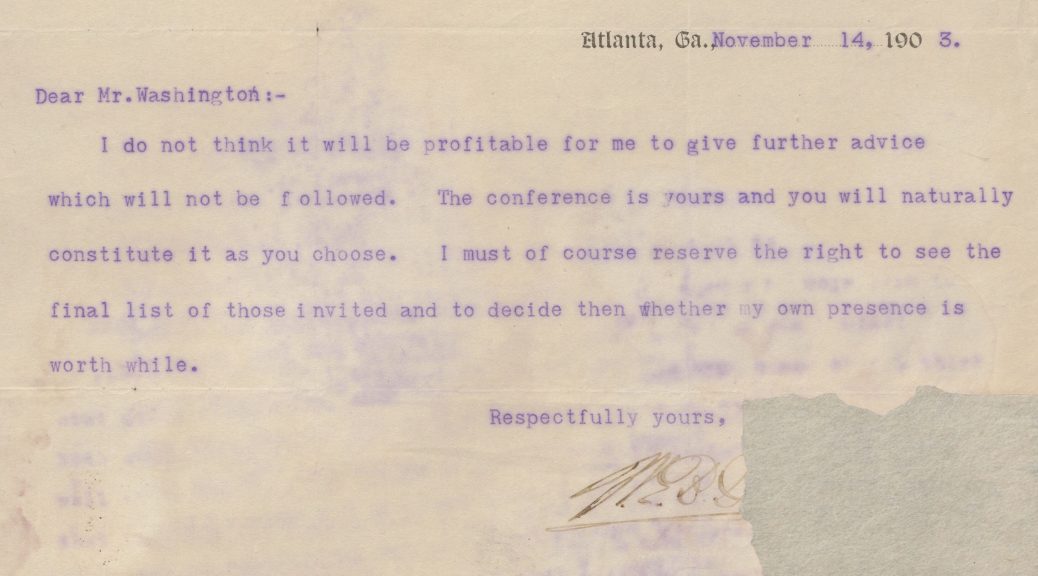

Before conversion, we complete one more round of quality control using the spot-checking process. We have even referred to other components of the Behind the Veil collection (Administrative and Project Files Administrative Files) to cross-reference any alterations to metadata for accuracy.

Connecting the Local and Larger Community

Throughout the project, team members have been working on outreach. One big accomplishment by project PI John Gartrell and former BTV outreach intern Brianna McGruder was “Behind the Veil at 30: Reflections on Chronicling African American Life in the Jim Crow South.” This 2-day virtual conference convened former BTV interviewers and current scholars of the BTV collection to discuss their work and the impact that this collection had on their research.

We also recently presented at the Triangle Research Libraries Network annual meeting, where our presentation overlapped with some of what you’ve just read in this post. It was exciting to share our work publicly for the first time and answer questions from library staff across the region. We will also be presenting a poster about our BTV experience at the upcoming North Carolina Library Association conference in Winston-Salem in October.

As we’ve hoped to convey, this project heavily relies on collaboration from many library departments and external vendors, and there are more contributors than we can thoroughly include in this post. Behind the Veil is a large-scale and high-profile project that has impacted many people over its 30-year history, and this newest iteration of digital accessibility seeks to expand the reach of this collection. Two years on, we’ve built on the work of the many professionals who have come before us to create and develop Behind the Veil. We are honored to be part of this rewarding process. Look for more BTV stories when we cross the finish line in 2024.