This post was written by Laurier Cress. Laurier Cress is a graduate student at the University of Denver studying Library Science with an emphasis on digital collections, rare books and manuscripts, and social justice in librarianship and archives. In addition to LIS topics, she is also interested in Medieval and Early Modern European History. Laurier worked as a practicum intern with the Digital Collections and Curation Services Department this winter to investigate auditing practices for decolonizing archival descriptions and metadata. Laurier will complete her masters degree in the Fall of 2021. In her spare time, she also runs a YouTube channel called, Old Dirty History, where she discusses historic events, people, and places throughout history.

Now that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) are popular concerns for libraries throughout the United States, discussions on DEI are inescapable. These three words have become reoccurring buzzwords dropped in meetings, classroom lectures, class syllabi, presentations, and workshops across the LIS landscape. While in some contexts, topics in DEI are thrown around with no sincere intent or value behind them, some institutions are taking steps to give meaning to DEI in librarianship. As an African American MLIS student at the University of Denver, I can say I have listened to one too many superficial talks on why DEI is important in our field. These conversations customarily exclude any examples on what DEI work actually looks like. When Duke Libraries advertised a practicum opportunity devoted to hands on experience exploring auditing practices for legacy metadata and harmful archival descriptions, I was immediately sold. I saw this experience as an opportunity to learn what scholars in our field are actually doing to make libraries a more equitable and diverse place.

As a practicum intern in Duke Libraries’ Digital Collections and Curation Services (DCCS) department, I spent three months exploring frameworks for auditing legacy metadata against DEI values and investigating harmful language statements for the department. Part of this work also included applying what I learned to Duke’s collections. Duke’s digital collections boasts 131,169 items and 997 collections, across 1,000 years of history from all over the world. Many of the collections represent a diverse array of communities that contribute to the preservation of a variety of cultural identities. It is the responsibility of institutions with cultural heritage holdings to present, catalog, and preserve their collections in a manner that accurately and respectively portrays the communities depicted within them. However, many institutions housing cultural heritage collections use antiquated archival descriptions and legacy metadata that should be revisited to better reflect 21st century language and ideologies. It is my hope that this brief overview on decolonizing archival collections not only aids Duke, but other institutions as well.

Harmful Language Statement Investigation

During the first phase of my investigation, I conducted an analysis on harmful language statements across several educational institutions throughout the United States. This analysis served as a launchpad for investigating how Duke can improve upon their inclusive description statement for their digital collections. During my investigation, I created a list that comprises of 41 harmful language statements. Some of these institutions include:

- The Walters Museum of Art

- Princeton University

- University of Denver

- Stanford University

- Yale University

After gathering a list of institutions with harmful language statements, the next phase of my investigation was to conduct a comparative analysis to uncover what they had in common and how they differed. For this analysis, 12 harmful language statements were selected at random from the total list. From this investigation, I created the Harmful Statement Research Log to record my findings. The research log comprises of two tabs. The first tab includes a list of harmful statements from 12 institutions, with supplemental comments and information about each statement. The second tab provides a list of 15 observations deduced from cross examining the 12 harmful language statements. Some observations made include placement, length, historical context, and Library of Congress Subject Heading (LCSH) disclaimers. It is important for me to note, while some of the information provided within the research log is based on pure observation, much of the report also includes conclusions based on personal opinions born from my own perspective as a user.

Decolonizing Archival Descriptions & Legacy Metadata

The next phase in my research was to investigate frameworks and current sentiments on decolonizing archival description and legacy metadata for Duke’s digital collections. Due to the limited amount of research on this subject, most of the information I came across was related to decolonizing collections describing Indigenous peoples in Canada and African American communities. I found that the influence of late 19th and early 20th centuries library classification systems can still be found within archival descriptions and metadata in contemporary library collections. The use of dated language within library and archival collections encourages the inequality of underrepresented groups through the promotion of discriminatory infrastructures established by these earlier classification systems. In many cases, offensive archival descriptions are sourced from donors and creators. While it is important for information institutions to preserve the historical context of records within their collections, descriptions written by creators should be contextualized to help users better understand the racial connotation surrounding the record. Issues regarding contextualizing racist ideologies from the past can be found throughout Duke’s digital collections.

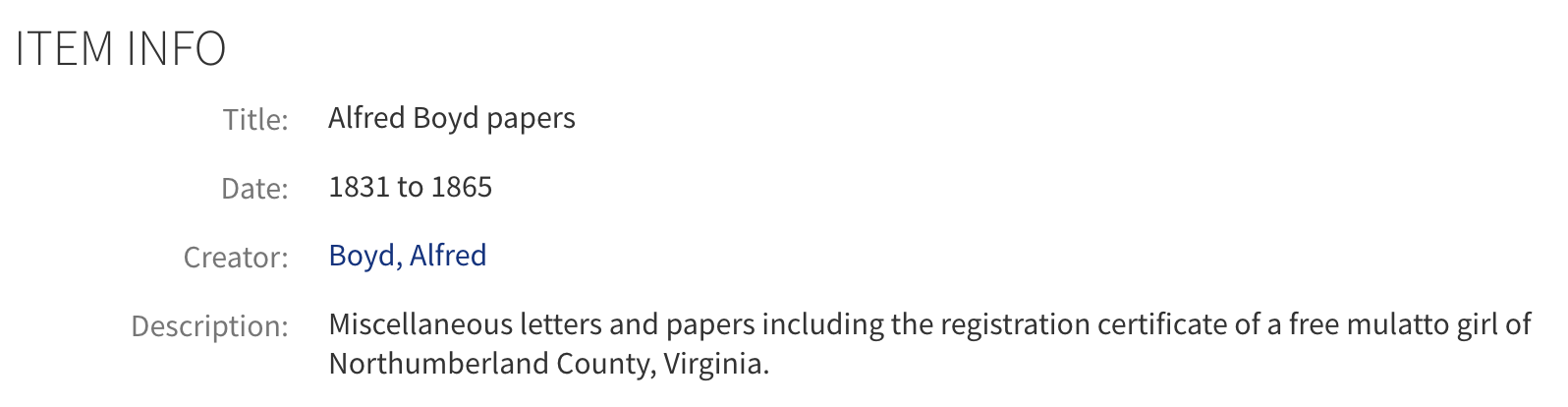

During my investigation, I examined Duke’s MARC records from the collection level to locate examples of harmful language used within their descriptions. The first harmful archival description I encountered was from the Alfred Boyd Papers. The archival description describes a girl referenced within the papers as “a free mulatto girl”. This is an example of when archival description should not shy away from the realities of racist language used during the period the collection was created in; however, context should be applied. “Mulatto” was an offensive term used during the era of slavery in the United States to refer to people of African and White European ancestry. It originates from the Spanish word “mulato”, and its literal meaning is “young mule”. While this word is used to describe the girl within the papers, it should not be used to describe the person within the archival description without historical context.

When describing materials concerning marginalized peoples, it is important to preserve creator-sourced descriptions, while also contextualizing them. To accomplish this, there should be a defined distinction between descriptions from the creator and the institution’s archivists. Some institutions, like The Morgan Library and Museum, use quotation marks as part of their in-house archival description procedure to differentiate between language originating from collectors or dealers versus their archivists. It is important to preserve contextual information, when racism is at the core of the material being described, in order for users to better understand the collection’s historic significance. While this type of language can bring about feelings of discomfort, it is also important to not allow your desire for comfort to take precedence over conveying histories of oppression and power dynamics. Placing context over personal comfort also takes the form of describing relationships of power and acts of violence just as they are. Acts of racism, colonization, and white supremacy should be labeled as such. For example, Duke’s Stephen Duvall Doar Correspondence collection describes the act of “hiring” enslaved people during the Civil War. Slavery does not imply hired labor because hiring implies some form of compensation. Slavery can only equate to forced labor and should be described as such.

Several academic institutions have taken steps to decolonize their collections. At the beginning of my investigation, a mentor of mine referred me to the University of Alberta Library’s (UAL) Head of Metadata Strategies, Sharon Farnel. Farnel and her colleagues have done extensive work on decolonizing UAL’s holdings related to Indigenous communities. The university declared a call to action to protect the representation of Indigenous groups and to build relationships with other institutions and Indigenous communities. Although UAL’s call to action not only encompasses decolonizing their collections, for the sake of this article, I will solely focus on the framework they established to decolonize their archival descriptions.

Community Engagement is Not Optional

Farnel and her colleagues created a team called the Decolonizing Description Working Group (DDWG). Their purpose was to propose a plan of action on how descriptive metadata practices could more accurately and respectfully represent Indigenous peoples. The DDWG included a Metadata Coordinator, a Cataloguer, a Public Service Librarian, a Coordinator of Indigenous Initiatives, and a self-identified Indigenous MLIS Intern. Much of their work consisted of consulting with the community and collaborating with other institutions. When I reached out to Farnel, she was so kind and generous with sharing her experience as part of the DDWG. Farnel told me that the community engagement approach taken is dependent on the community. Marginalized peoples are not a monolith; therefore, there is no “one size fits all” solution. If you are going to consult community members, recognize the time and expertise the community provides. This relationship has to be mutually beneficial, with the community’s needs and requests at the forefront at all times.

For the DDWG, the best course of action was to start building a relationship with local Indigenous communities. Before engaging with the entire community, the team first engaged with community elders to learn how to proceed with consulting the community from a place of respect. Because the DDWG’s work took place prior to COVID-19, most meetings with the community took place in person. Farnel refers to these meetings as “knowledge gathering events”. Food and beverages were provided and a safe space for open conversation. A community elder would start the session to set the tone.

In addition to knowledge gathering events, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students and alumni were consulted through an informal short online survey. The survey was advertised through an informal social media posting. Once the participants confirmed the desire to partake in the survey, they received an email with a link to complete it. Participants were asked questions based on their feelings and reactions to potentially changing the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) that related to Aboriginal content.

Auditing Legacy Metadata and Archival Descriptions

There is more than one approach an institution can take to start auditing legacy metadata and descriptions. In a case study written by Dorothy Berry, who is currently the Digital Collections Program Manager at Harvard’s Houghton Library, she describes a digitization project that took place at the University of Minnesota Libraries. The purpose of the project was to not only digitize African American heritage materials within the university’s holdings, but to also explore ways mass digitization projects can help re-aggregate marginalized materials. This case study serves as an example of how collections can be audited for legacy metadata and archival descriptions during mass digitization projects. Granted, this specific project received funding to support such an undertaking and not all institutions have the amount of currency required to take on an initiative of this magnitude. However, this type of work can be done slowly over a longer period of time. Simply running a report to search for offensive terms such as “negro”, or in my case “mulatto”, is a good place to start. Be open to having discussions with staff to learn what offensive language they also have come across. Self-reflection and research are equally important. Princeton University Library’s inclusive description working group spent two years researching and gathering data on their collections before implementing any changes. Part of their auditing process also included using a XQuery script to locate harmful descriptions and recover histories that were marginalized due to lackluster description.

Creators Over Community = Problematic

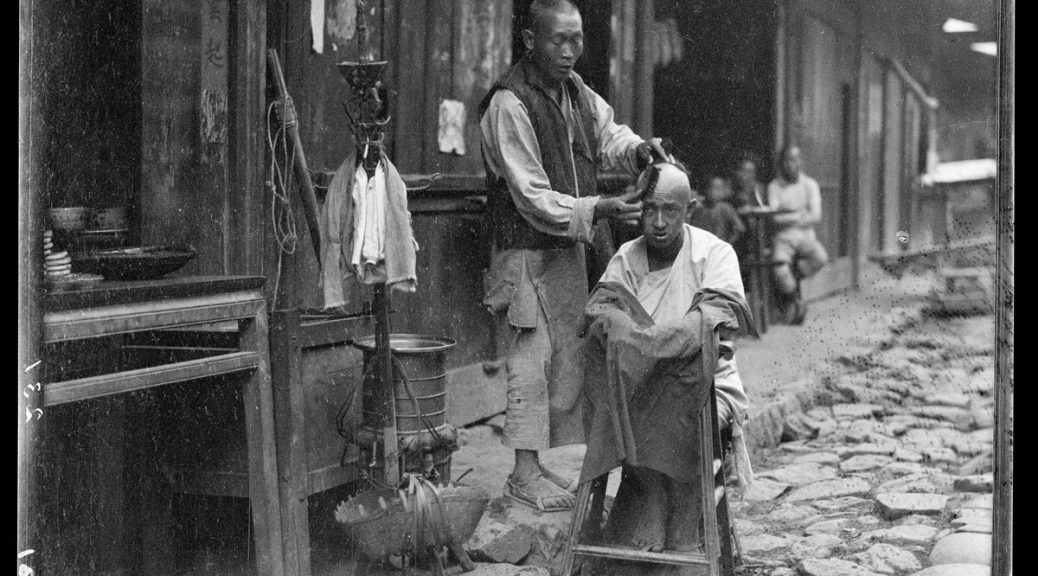

While exploring Duke’s digital collections, one problem that stood out to me the most was the perpetual valorization of creators. This is often found in collections with creators who are white men. Adjectives like “renowned”, “genius’, “talented”, and “preeminent” are used to praise the creators and make the collection more about them instead of the community depicted within the collection. An example of this troublesome language can be found in Duke’s Sidney D. Gamble’s Photographs collection. This collection comprises of over 5,000 black and white photographs taken by Sidney D. Gamble during his four visits to China from 1908 to 1932. Content within the photographs encompass depictions of people, architecture, livestock, landscapes, and more. Very little emphasis is placed on the community represented within this collection. Little, if any, historical or cultural context is given to help educate users on the culture behind the collection. And the predominate language used here is English. However, there is a

full page of information on the life and exploits of Gamble.

Describing Communities

Harmful language used to describe individuals represented within digital collections can be found everywhere. This is not always intentional. Dorothy Berry’s presentation with the Sunshine State Digital Network on conscious editing serves as a great source of knowledge on problematic descriptions that can be easily overlooked. Some of Berry’s examples include:

- Class: Examples include using descriptions such as “poor family” or “below the poverty line”.

- Race & Ethnicity: Examples include using dehumanizing vocabulary to describe someone of a specific ethnicity or excluding describing someone of a specific race within an image.

- Gender: Example includes referring to a woman using her husband’s full name (Mrs. John Doe) instead of her own.

- Ability: Example includes using offensive language like “cripple” to describe disabled individuals.

This is only a handful of problematic description examples from Berry’s presentation. I highly recommend watching not only Berry’s presentation, but the entire Introduction to Conscious Editing Series.

Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) Are Unavoidable

I could talk about LCSH in relation to decolonizing archival descriptions for days on end, but for the sake of wrapping up this post I won’t. In a perfect world we would stop using LCSH altogether. Unfortunately, this is impossible. Many institutions use custom made subject headings to promote their collections respectfully and appropriately. However, the problem with using custom made subject headings that are more culturally relevant and respectful is accessibility. If no one is using your custom-made subject headings when conducting a search, users and aggregators won’t find the information. This defeats the purpose of decolonizing archival collections, which is to make collections that represent marginalized communities more accessible.

What we can do is be as cognizant as possible of the LCSHs we are using and avoid harmful subject headings as much as possible. If you are uncertain if a LCSH is harmful, conduct research or consult with communities who desire to be part of your quest to remove harmful language from your collections. Let your users know why you are limited to subject headings that may be harmful and that you recognize the issue this presents to the communities you serve. Also consider collaborating with Cataloginglab.org to help design new LCSH proposals and to stay abreast on new LCSH that better reflect DEI values. There are also some alternative thesauri, like homosaurus.org and Xwi7xwa Subject Headings, that better describe underrepresented communities.

Resources

In support of Duke Libraries’ intent to decolonize their digital collections, I created a Google Drive folder that includes all the fantastic resources I included in my research on this subject. Some of these resources include metadata auditing practices from other institutions, recommendations on how to include communities in archival description, and frameworks for decolonizing their descriptions.

While this short overview provides a wealth of information gathered from many scholars, associations, and institutions who have worked hard to make libraries a better place for all people, I encourage anyone reading this to continue reading literature on this topic. This overview does not come close to covering half of what invested scholars and institutions have contributed to this work. I do hope it encourages librarians, catalogers, and metadata architects to take a closer look at their collections.