Over the past couple of years I’ve written on this blog about the kinds of initiatives libraries are engaging in these days in order to try to wrestle with our past (and sometimes, current) problematic practices when creating the descriptive metadata patrons use to discover and identify library resources. And last spring we hosted an intern in the Digital Collections and Curation Services department, Laurier Cress, who wrote an excellent piece describing her research and investigation into the issues present in library and archival description as well as actions that can be taken to address them.

One of the first steps that institutions can take is to publicly acknowledge that we are aware of the biases in our cataloging practices and the resulting harmful or otherwise problematic metadata in our catalogs and on our websites, and to make a commitment to remediation. These public acknowledgements often take the form of what is typically referred to as a ‘harmful language statement’ on the library’s website (The Cataloging Lab has created what looks to be a pretty comprehensive list of statements on bias in library and archives description). Last spring, our Executive Group convened a working group to develop such a statement for the Duke University Libraries and charged us with: Using harmful language statements drafted by other cultural heritage groups as a reference, draft statements acknowledging harmful language and content within our collections (digital and analog) and metadata.

The working group started by reviewing the Harmful Statement Research Log Laurier had compiled as part of her research, in which she analyzed the content and presentation of harmful language statements from GLAM institutions. This was extremely helpful to us in determining what we wanted to prioritize and emphasize as we developed our own statement. We met biweekly over the course of a few months, while also working asynchronously on verbiage in between meetings. Ultimately, we decided that we wanted our statement to be straightforward, communicating that we know library description is not a neutral space, that we are aware that harmful language exists on our website, and that we are committed to repairing such language as it is identified. We also wanted our statement to be short – no one likes a wall of text! – and we were able to accomplish this by linking from the statement to lengthier, more detailed statements on inclusive description prepared by our Technical Services division and the Rubenstein Libraries Technical Services department.

We also felt it was important that our statement include a mechanism for soliciting feedback from users, and so we created a Qualtrics form, linked from the statement, that allows people who have encountered harmful or otherwise problematic language on our website to report it to us. Responses may be anonymous, if desired, although it is also possible to share contact information in order to be updated about any actions taken to remediate the language. Both the statement and the form were published this week:

Read DUL’s Statement on Potentially Harmful Language in Library Descriptions.

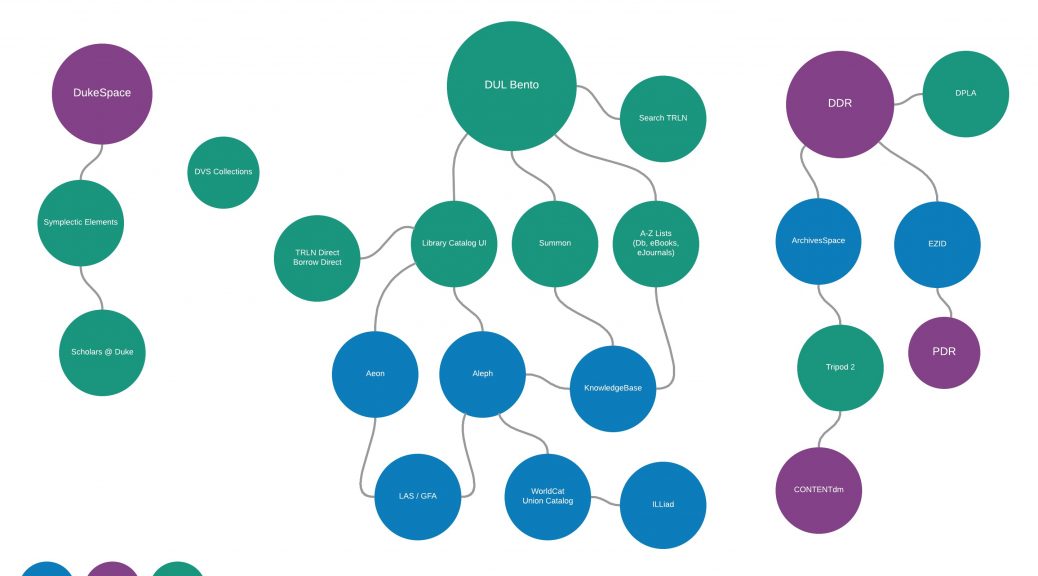

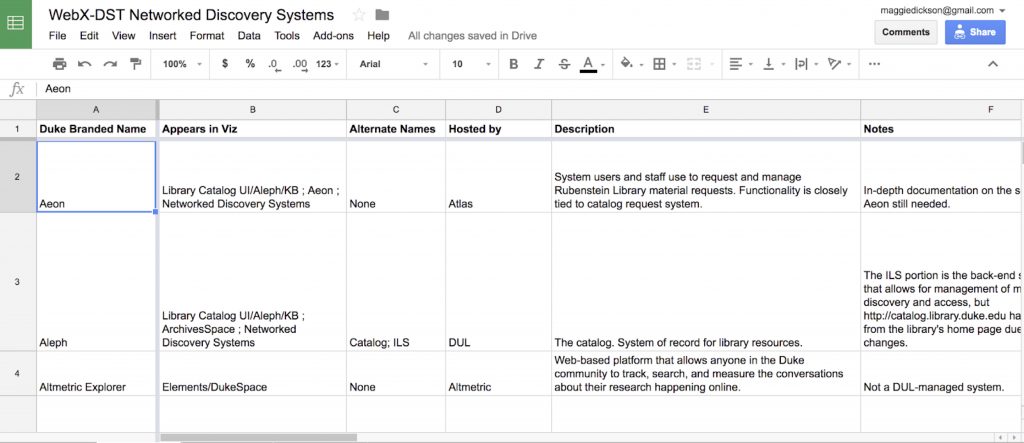

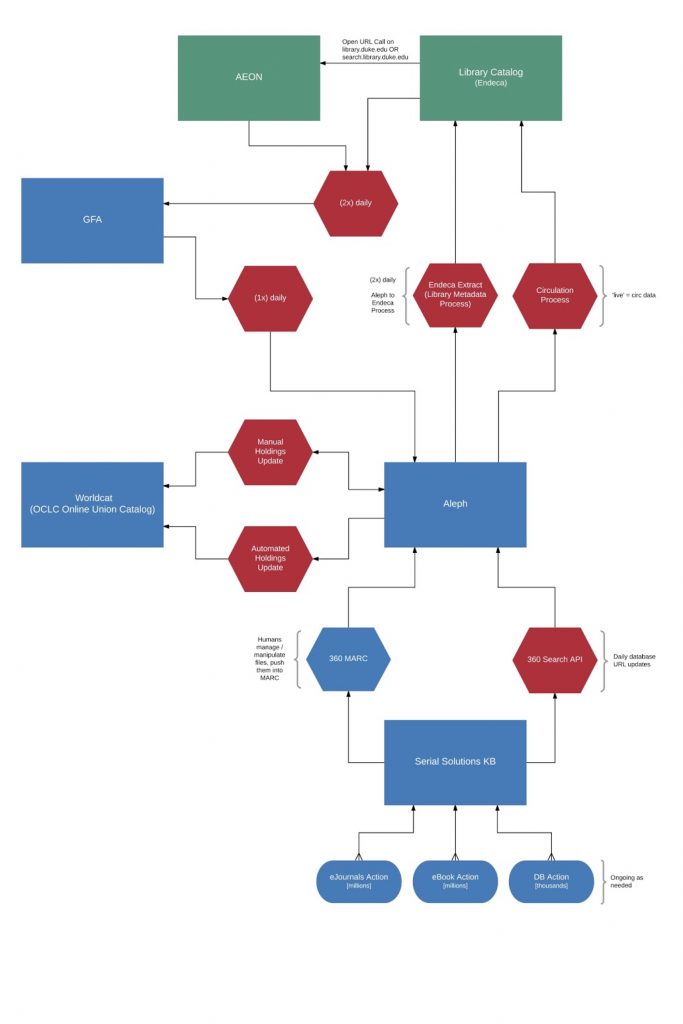

And we’re not done here! A third priority of the working group’s, in addition to the creation of the statement and the feedback form, was to ensure that this work be visible. (E.g., ‘if a tree falls in a forest, but no one is there to hear it fall, did it make a sound?’ is not dissimilar to ‘if a Drupal page gets plopped into a vast academic research library website, but nobody can find it, will it make an impact?’) To that end, now that the statement and form are publicly accessible, we will work to add links to the statement throughout our discovery layer (including our catalog, our digital collections, and archival collection guides) so that users will be able to find it at the point at which they are potentially encountering harmful language. This work will be a bit more complicated than creating Drupal pages and Qualtrics forms, however, so please stay tuned!