Located amongst agricultural fields, grazing cattle and goats, the quiet town of Boğazkale watches time pass. It is a small town in the Black Sea region of Turkey, only about 1300 people live here. You are more likely to encounter a tractor than a car and you get the sense that everyone knows everyone else. If you walk about half a kilometer outside of this sleepy community, you will encounter the equally serene-looking archaeological site of Hattusa. Although now abandoned, at its peak in the 14th century BC, Hattusa was a capital and home to nearly 50,000 Hittites.

Much of what is known about the Hittites is drawn from their own writings, or from later copies of their writings. The Hittites have been described by some sources as warlike; they utilized chariots and steadily increased their kingdom. They worked iron and had a fair amount of courtly intrigue. Perhaps most importantly, the Hittites were literate, employing an Indo-European language with an Akkadian script.

Around 1177 BC, Hattusa fell as one of many victims of the Late Bronze Age Collapse. There is archaeological evidence for extensive burning at the site and the written records at Hattusa stop. It appears as though the site was gradually abandoned over time and never successfully reoccupied. That turned out to be a stroke of luck because a German archaeological dig in the early 20th century (re)discovered the so-called Bogazköy Archive, which was determined initially to be a largely intact royal archive. Thanks to more research and the decipherment of the Hittite language in 1915, it seems more likely that this assemblage of 30,000 cuneiform tablets is actually a library. This is based largely on the argument that some of the tablets have colophons that provide an order hierarchy for multi-part works and the collection includes basic descriptive inventory lists of the tablets, instituting an early type of collection management.

The abandonment of Hattusa and its library makes one wonder: What would it have been like for the scribes or library keepers to make the decision to leave the collection? What would they have done to get the collection ready for their absence? What would have the last person who left the collection felt like upon leaving? Did they believe they would return?

It’s impossible to answer such questions, since we have no surviving first-person accounts from this event. However, we can consider a current analogy and while it’s not a perfect correspondence, it may provide some emotional experiential equivalence.

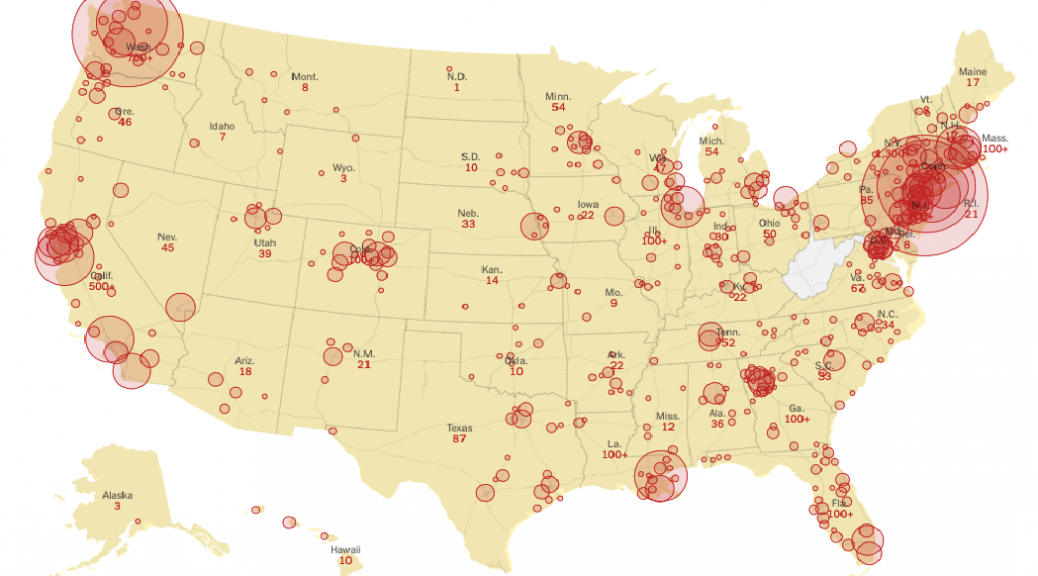

With the advent of the 2019-2020 coronavirus pandemic, many universities and cultural heritage institutions were faced with the difficult challenge of abiding by official orders, trying to keep their faculty and staff safe and healthy, and attempting to continue with business as usual. At Duke University Libraries, the decision-making process began publicly at the beginning of March 2020. It started with one email, a few days’ pause, and then another email and the information about how the Libraries would ultimately face the pandemic trickled in. Eventually, it became one or more emails everyday with updates. The Libraries scaled back opening times and access to staff and eventually made the onerous decision to close the Libraries on March 20, 2020.

The last week that the Libraries were open, staff were encouraged to begin setting up to work from home and to come up with ideas of what work could be done remotely. Colleagues began making the transition from being in the Library to being at home. In the Digital Production Center (DPC), our small workgroup of 4 individuals slowly began to dwindle as one-by-one co-workers began working from home.

So, what did the DPC do to get ready for the Libraries’ closure? Our primary remit as a department is to produce digital surrogates of Duke’s collection items both for online use and for library patrons. So, we worked hard to get items digitized for online class use, patrons and online collections. It was a race against time because we knew that whatever we didn’t have imaged by Friday at 5pm would have to wait. And for online courses that were counting on the material, waiting wasn’t an option. Normally, the DPC holds materials that we are working with in our vault. However, with the Library closing down, those items needed to be secured in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. We took several carts full of materials back for safe keeping, with the idea that we would retrieve them when the Libraries reopen.

As the number of staff physically onsite in the Library began to diminish, I started saying goodbye to more people than hello. With every farewell, there was uncertainty: When will we see each other again? The Library became a truly quiet place. Gone were the patrons and students, replaced by empty seats and a deafening silence. Colleagues that I would normally pass in the Library several times a week suddenly began showing up on my computer screen for Zoom meetings.

On the final day that the Libraries were open to staff, the last batch of materials was returned to the Rubenstein Library for safekeeping and the Libraries themselves had transformed into very different, very empty spaces. While the circumstances are certainly not the same as they were for the Hittites, there was a sense of uncertainty. I’d like to believe that I was more assured of my return to the Library than that last scribe or keeper.

As I left Perkins Library, I paused in the doorway and looked back over my shoulder. I didn’t know when I might be back. I turned and exited into the warm Spring day on an empty Duke campus, and just like the last scribe or keeper, I was stepping into an unfamiliar future.

Epilogue

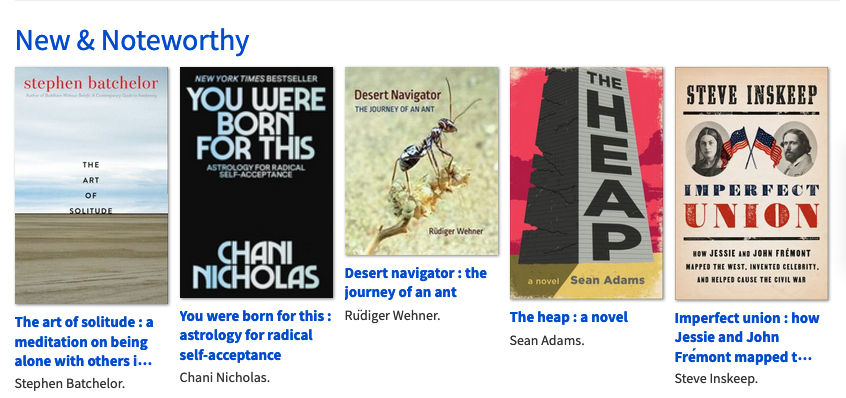

Although as of March 27, 2020, Duke University Libraries are currently closed, the Libraries anticipate reopening as soon as it is safe and prudent to do so. In the meantime, you can find a list of services still available during this closure here.

Sources

Bryce, Trevor. The Kingdom of the Hittites. Rev. ed. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Casson, Lionel. Libraries of the Ancient World. Yale University, 2001.

Roaf, Michael. Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. Facts on File, 1990.

van den Hout, Theo P.J. “Miles of Clay: Information Management in the Ancient Near Eastern Hittite Empire.” Fathom Archive, The University of Chicago, 26 October 2002, http://fathom.lib.uchicago.edu/1/777777190247/.

Further Reading

Cline, Eric H. 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press, 2014. An overview of the Late Bronze Age Collapse, with thanks to the author for his suggestion.

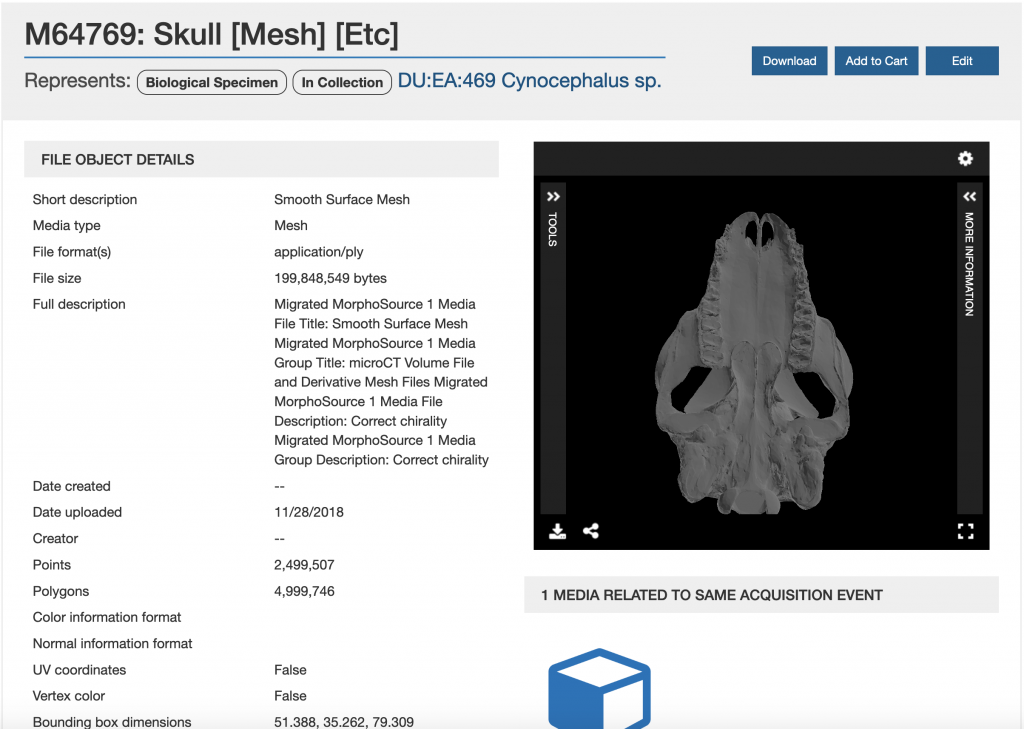

Header Image: Collection of extinct and extant turtle skull microCT scans in MorphoSource:

Header Image: Collection of extinct and extant turtle skull microCT scans in MorphoSource: