The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is now accepting applications for our 2022-2023 research travel grants. If you are a researcher, artist, or activist who would like to use sources from the Rubenstein Library’s research centers for your work, this means you!

Research travel grants of up to $1500 are offered by the following Centers and research areas:

- Archive of Documentary Arts

- Harry H. Harkins T’73 Travel Grants for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender History

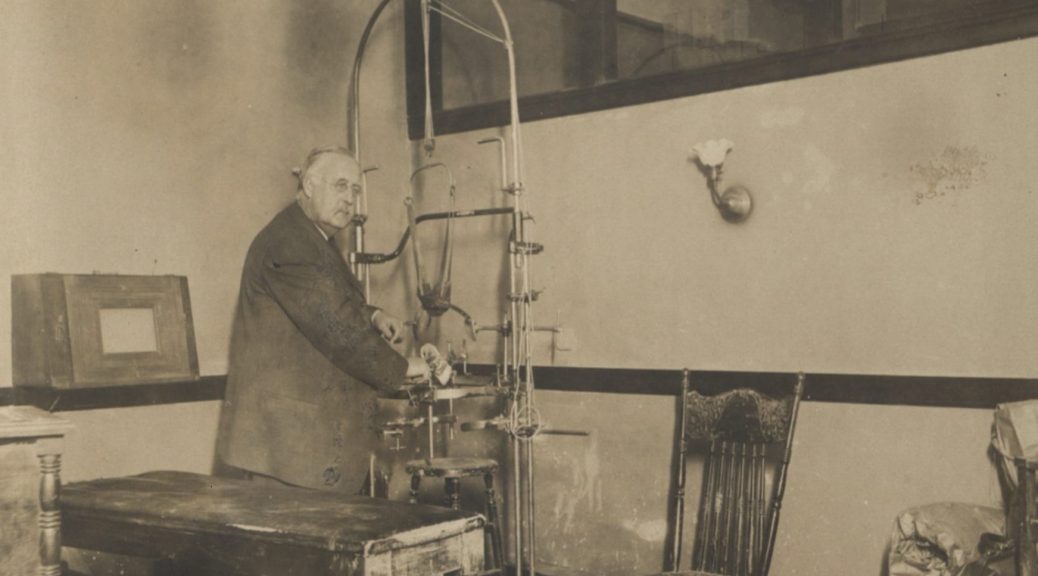

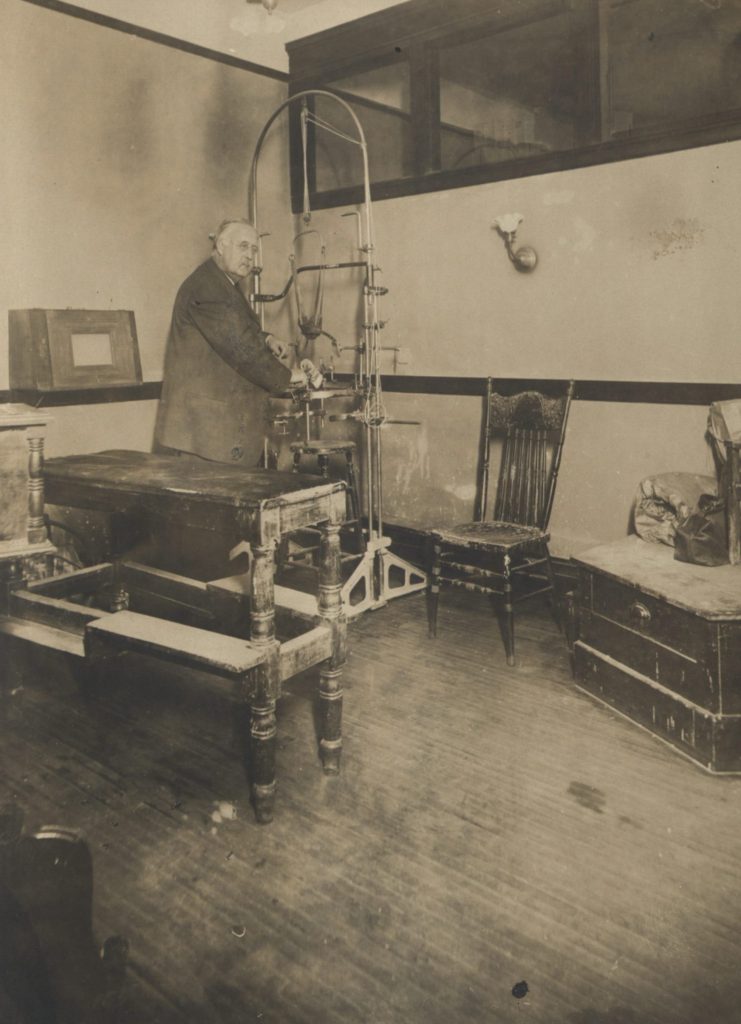

- History of Medicine Collections

- Human Rights Archive

- John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History and Culture

- John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History

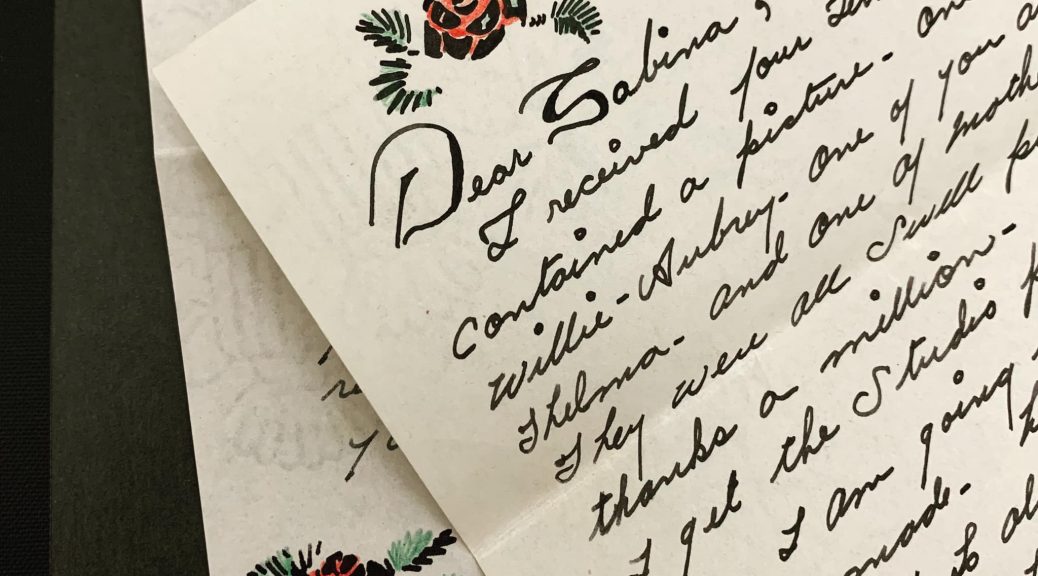

- Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture (Mary Lily Research Grants)

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick Papers

We encourage applications from students at any level of education; faculty members; visual and performing artists; writers; filmmakers; public historians; and independent researchers. (Must reside beyond a 100-mile radius of Durham, N.C., and may not be current Duke students or employees.) These grants are offered as reimbursement based on receipt documentation after completion of the research visit(s). The deadline for applications will be Saturday, April 30, 2022, at 6:00 pm EST. Grants will be awarded for travel during June 2022-June 2023.

An information session will be held Wednesday, March 23rd at 2PM EST. This program will review application requirements, offer tips for creating a successful application, and include an opportunity for attendees to ask questions. Register for the session here. Further questions may be directed to AskRL@duke.edu.

Image citation: Cover detail from African American soldier’s Vietnam War photograph album https://idn.duke.edu/ark:/87924/r4319wn3g

For many towns and cities in 20th century America, the holiday season officially began just after Thanksgiving, which was established as a fixed national holiday in 1941. Frequently festivities included a parade that involved local dignitaries, youth clubs, business and social organizations, a Miss Something-or-Other pageant winner, high school bands, fire engines, culminating in the arrival of Santa Claus in some ostentatious conveyance. Town folk stood in yards and sidewalks, sometimes for hours in freezing weather, to witness the spectacle. To this day, even, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade ends with the Santa Claus float.

For many towns and cities in 20th century America, the holiday season officially began just after Thanksgiving, which was established as a fixed national holiday in 1941. Frequently festivities included a parade that involved local dignitaries, youth clubs, business and social organizations, a Miss Something-or-Other pageant winner, high school bands, fire engines, culminating in the arrival of Santa Claus in some ostentatious conveyance. Town folk stood in yards and sidewalks, sometimes for hours in freezing weather, to witness the spectacle. To this day, even, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade ends with the Santa Claus float.