Post contributed by Kaylee P. Alexander, Eleonore Jantz Reference Intern 2020-2021.

Bumper stickers, a MAGA hat, a Hillary Clinton nutcracker, ads for Dick Nixon jewelry, and a Barry Goldwater beer can are just some of the relics of past presidential campaigns to be found in the over thirty boxes of the Kenneth Hubbard Collection of Presidential Campaign Ephemera at the Rubenstein Library. Gimmicky, kitschy and teeming with bad puns, objects such as these have become somewhat ubiquitous in American campaign culture, and the Hubbard Collection covers nearly every presidential campaign that took place between 1828 and 2016. Representing Republicans and Democrats—both winners and losers—as well as candidates running with the U.S. Socialist and Prohibitionist parties, the Hubbard collection provides interesting material and visual cultural insights in the history of American elections by demonstrating a wide range of strategies for advertising and showing support for would-be U.S. presidents.

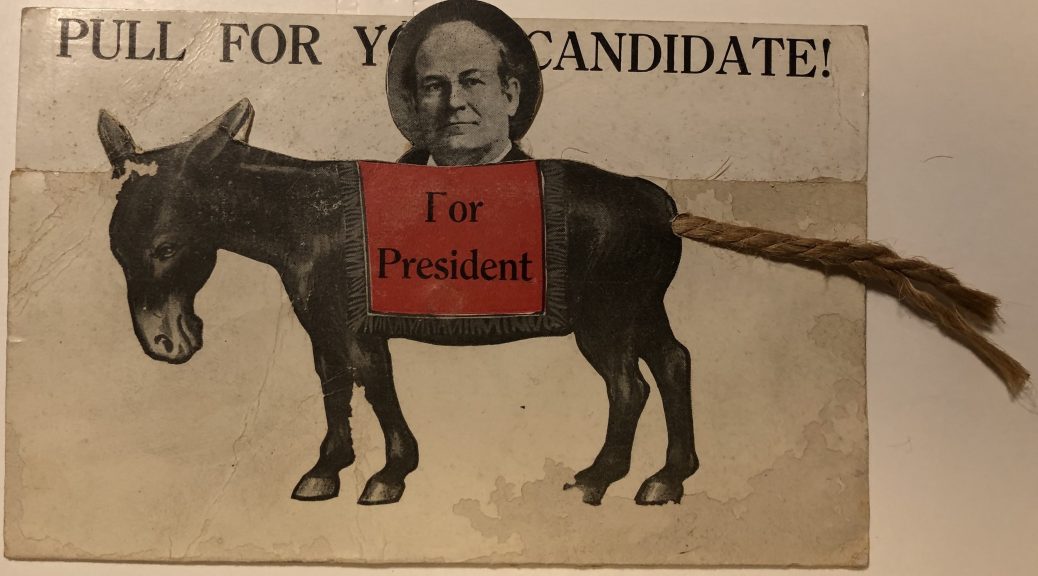

Going through these boxes over the past month, I was not shocked to find what seemed like an endless supply of buttons, pins and ribbons. Nor was I very surprised to find objects such as that Hillary nutcracker, or the Bill Clinton tie that was kept in the box alongside it; these ridiculous artifacts seemed somewhat logical to me, having seen the bizarre assortment of collectibles—from bobble heads and action figures to, most recently, facemasks—for candidates who have run in my lifetime. No matter how many objects or documents I came across in the collection, however, I couldn’t stop thinking about the first folder I had pulled: a folder containing just one postcard, with a donkey illustration and twine tail. “Pull for Your Candidate,” the postcard instructed, and, in an oddly amusing sort of way, a portrait of William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925) emerged above the donkey as you pulled on its tail. I couldn’t help but chuckle.

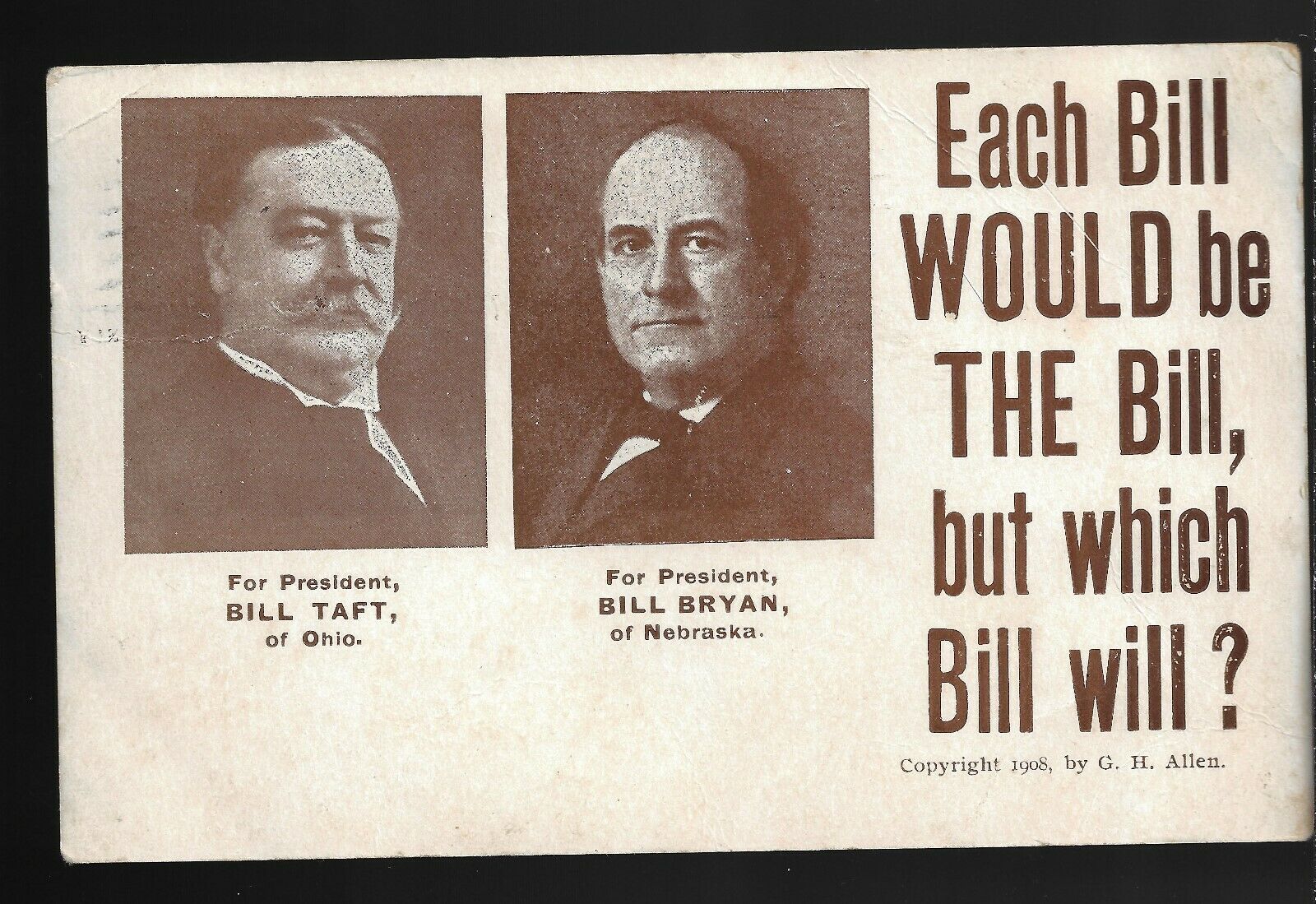

Printed by the Elite Post Card Company of Kansas City, Missouri, the verso provided space for you to compose your own message and address the card to whomever you wanted to send it to. Designed for the 1908 presidential election, in which Bryan faced off against Theodore Roosevelt’s Secretary of War, William H. Taft in a “battle of the Bills,” the postcard provided an attention-grabbing method of advocating for one’s presidential pick, not unlike today’s letter writing campaigns, or even contemporary social media activity urging folks to get out and vote.

A proponent of a progressive income tax and stronger antitrust laws, Bryan was hailed “The great Commoner.” 1908 would be the third and final time that Bryan, formerly Nebraska’s 1st District Representative, would run for president. Unfortunately, it would also be his biggest defeat, earning just 162 electoral votes to Taft’s 321. With Taft’s defeat after one term by New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson, Bryan would serve as Secretary of State from 1913 to 1915. Despite his presidential losses, however, Bryan is still considered to be one of the most influential, albeit somewhat controversial, politicians of the Progressive Era.

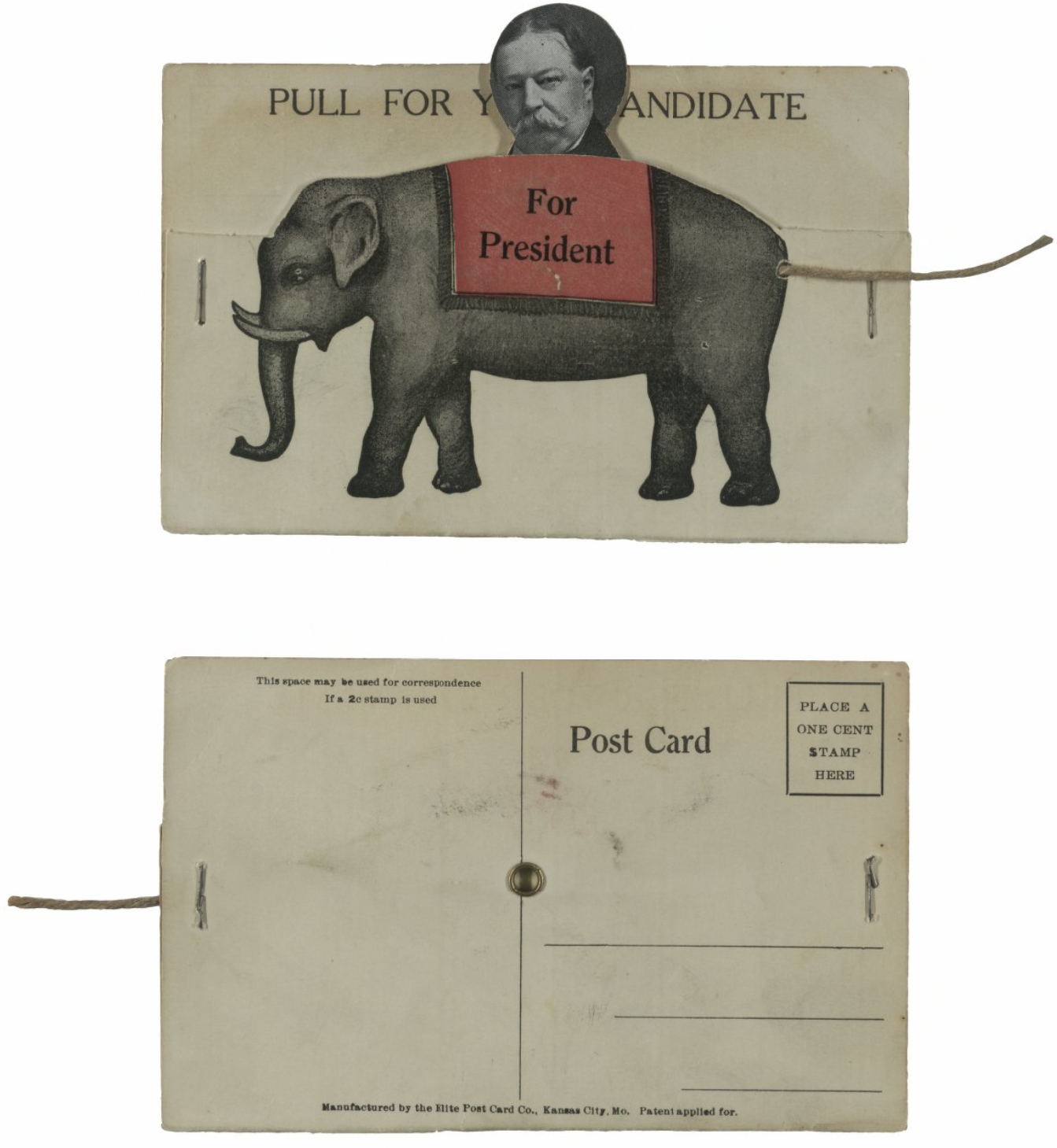

A bit of digging revealed that a Republican version of the 1908 postcard, featuring an elephant in place of the donkey, had also been produced for Taft, an example of which can be found in the Dr. Allen B. and Helen S. Shopmaker American Political Collection of the St. Louis Mercantile Library Art Museum at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. With both of these postcards available to potential voters, one would have been able to literally and figuratively pull for their candidate and motivate others to do so as well.

So, with a few days to go before Election Day, be sure to take a lesson from the Elite Postcard Company and pull for your candidate. Every vote matters.

Given this context, it was newsworthy when Wilhelmina Reuben, a member of Duke’s first class of Black undergraduates, was

Given this context, it was newsworthy when Wilhelmina Reuben, a member of Duke’s first class of Black undergraduates, was