Its that time of year when all the year end “best of” lists come out, best music, movies, books, etc. Well, we could not resist following suit this year, so… Ladies in gentlemen, I give you in – no particular order – the 2015 best of list for the Digital Projects and Production Services department (DPPS).

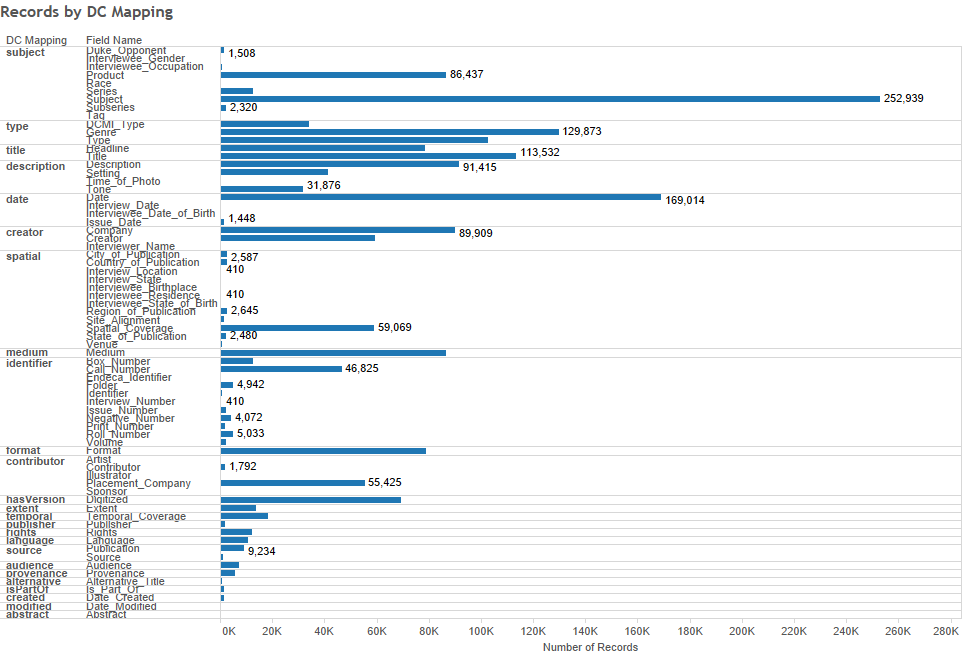

Metadata Architect

In 2015, DPPS welcomed a new staff member to our team; Maggie Dickson came on board as our metadata architect! She is already leading a team to whip our digital collections metadata into shape, and is actively consulting with the digital repository team and others around the library. Bringing metadata expertise into the DPPS portfolio ensures that collections are as discoverable, shareable, and re-purposable as possible.

King Intern for Digital Collections

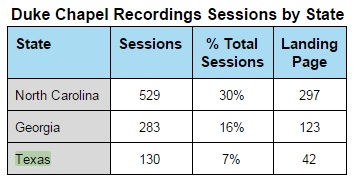

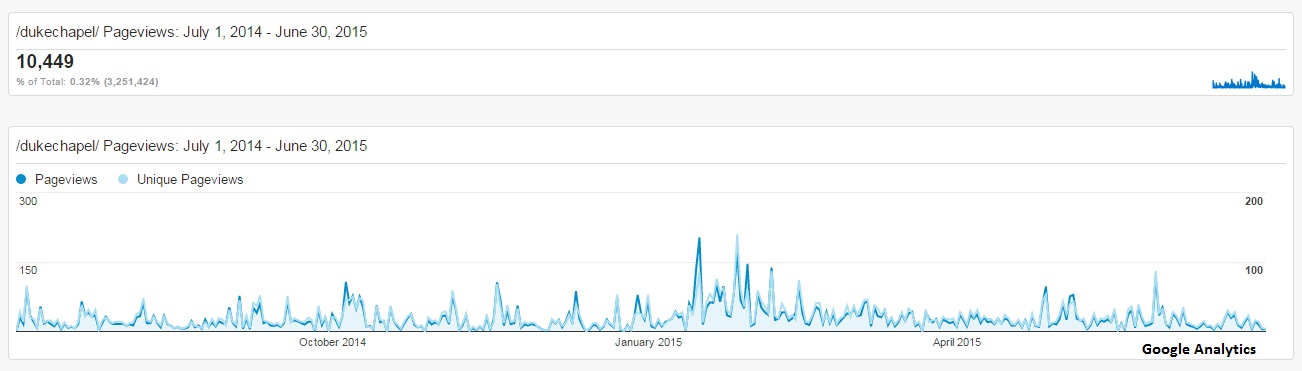

DPPS started the year with two large University Archives projects on our plates: the ongoing Duke University Chronicle digitization and a grant to digitize hundreds of Chapel recordings. Thankfully, University Archives allocated funding for us to hire an intern, and what a fabulous intern we found in Jessica Serrao (the proof is in her wonderful blogposts). The internship has been an unqualified success, and we hope to be able to repeat such a collaboration with other units around the library.

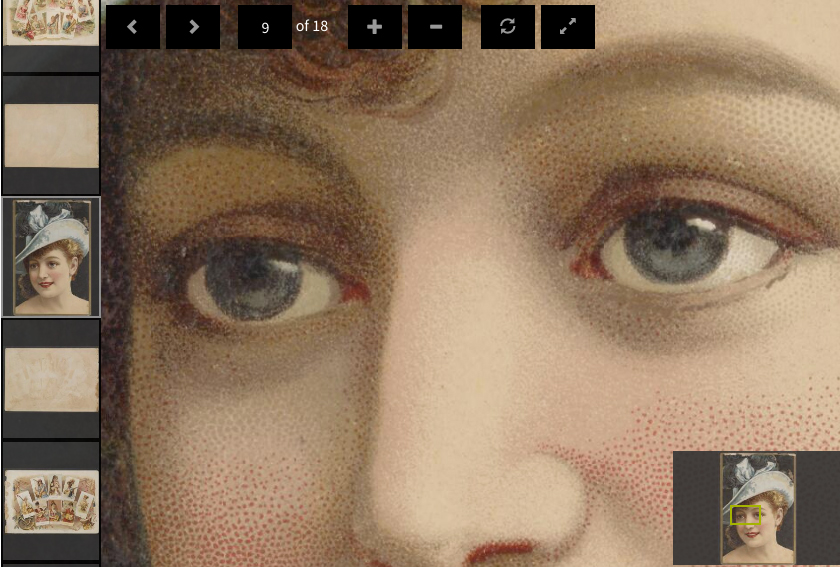

Tripod 3

Tripod 3

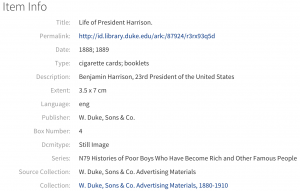

Our digital project developers have spent much of the year developing the new Tripod3 interface for the Duke Digital Repository. This process has been an excellent opportunity for cross departmental collaborative application development and implementing Agile methodology with sprints, scrums, and stand up meetings galore! We launched our first collection not the new platform in October and we will have a second one out the door before the end of this year. We plan on building on this success in 2016 as we migrate existing collections over to Tripod3.

Repository ingest planning

Speaking of Tripod3 and the Duke Digital Repository, we have ingesting digital collections into the Duke Digital Repository since 2014. However, we have a plan to kick ingests up a notch (or 5). Although the real work will happen in 2016, the planning has been a long time coming and we are all very excited to be at this phase of the Tripod3 / repository process (even if it will be a lot of work). Stay tuned!

Digital Collections Promotional Card

Digital Collections Promotional Card

This is admittedly a small achievement, but it is one that has been on my to-do list for 2 years so it actually feels like a pretty big deal. In 2015, we designed a 5 x 7 postcard to hand out during Digital Production Center (DPC) tours, at conferences, and to any visitors to the library. Also, I just really love to see my UNC fan colleagues cringe every time they turn the card over and see Coach K’s face. Its really the little things that make our work fun.

New Exhibits Website

In anticipation of opening of new exhibit spaces in the renovated Rubenstein library, DPPS collaborated with the exhibits coordinator to create a brand new library exhibits webpage. This is your one stop shop for all library exhibits information in all its well-designed glory.

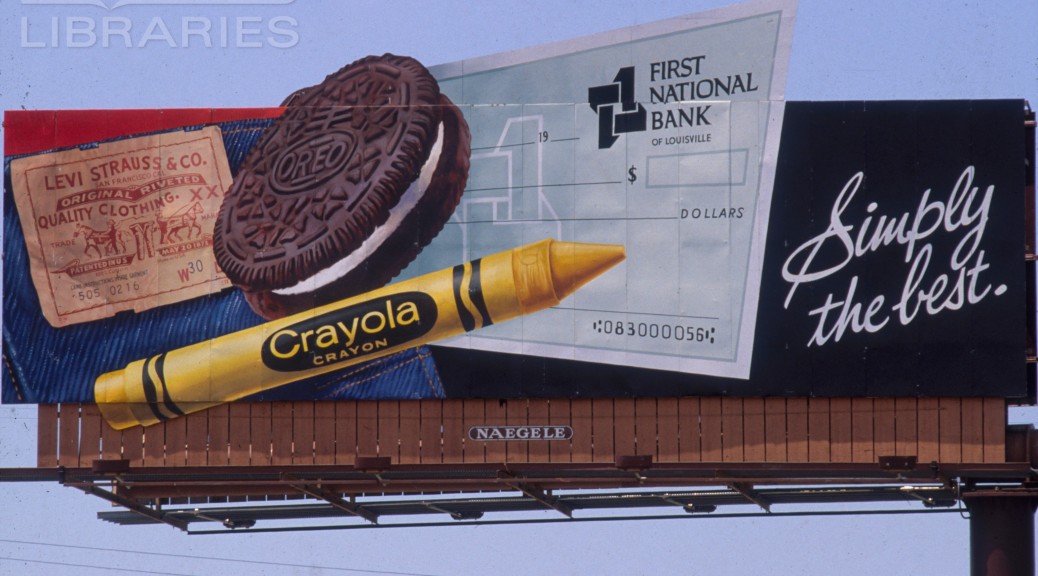

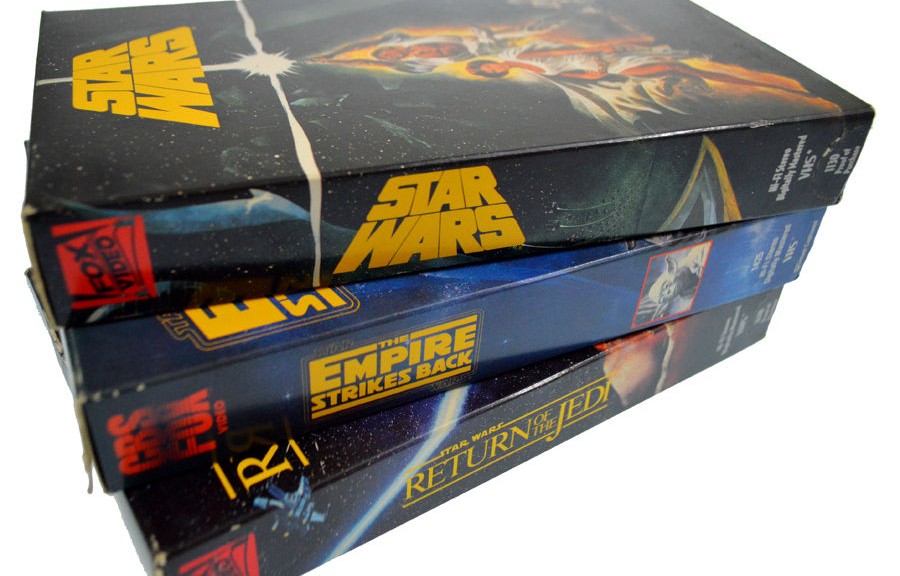

Audio and Video Preservation

In 2014, the Digital production Center bolstered workflows for preservation based digitization. Unlike our digital collections projects, these preservation digitization efforts do not have a publication outcome so they often go unnoticed. Over the past year, we have quietly digitized around 400 audio cassettes in house (this doesn’t count outsourced Chapel Recordings digitization), some of which need to be dramatically re-housed.

On the video side, efforts have been sidelined by digital preservation storage costs. However some behind the scenes planning is in the works, which means we should be able to do more next year. Also, we were able to purchase a Umatic tape cleaner this year, which while it doesn’t sound very glamorous to the rest of the world, thrills us to no end.

Revisiting the William Gedney Digital Collection

Fans of Duke Digital Collections are familiar with the current Gedney Digital Collection. Both the physical and digital collection have long needed an update. So in recent years, the physical collection has been reprocessed, and this Fall we started an effort to digitized more materials in the collection and to higher standards than were practical in the late 1990s.

Expanding DPC

When the Rubenstein Library re-opened, our neighbor moved into the new building, and the DPC got to expand into his office! The extra breathing room means more space for our specialists and our equipment, which is not only more comfortable but also better for our digitization practices. The two spaces are separate for now, but we are hoping to be able to combine them in the next year or two.

2015 was a great year in DPPS, and there are many more accomplishments we could add to this list. One of our team mottos is: “great productivity and collaboration, business as usual”. We look forward to more of the same in 2016!

![The sun. (New York [N.Y.]), 21 July 1871. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.](https://blogs.library.duke.edu/bitstreams/files/2015/11/ny-sun-chronicling-america-1024x330.jpg)