We have a few new exciting enhancements within our digital collections and archival collection guide interfaces to share this week, all related to the challenge of presenting the proper archival context for materials represented online. This is an enormous problem we’ve previously outlined on this blog, both in terms of reconciling different descriptions of the same things (in multiple metadata formats/systems) and in terms of providing researchers with a clear indication of how a digitized item’s physical counterpart is arranged and described within its source archival collection.

Here are the new features:

View Item in Context Link

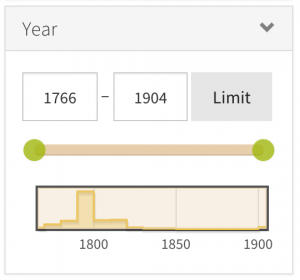

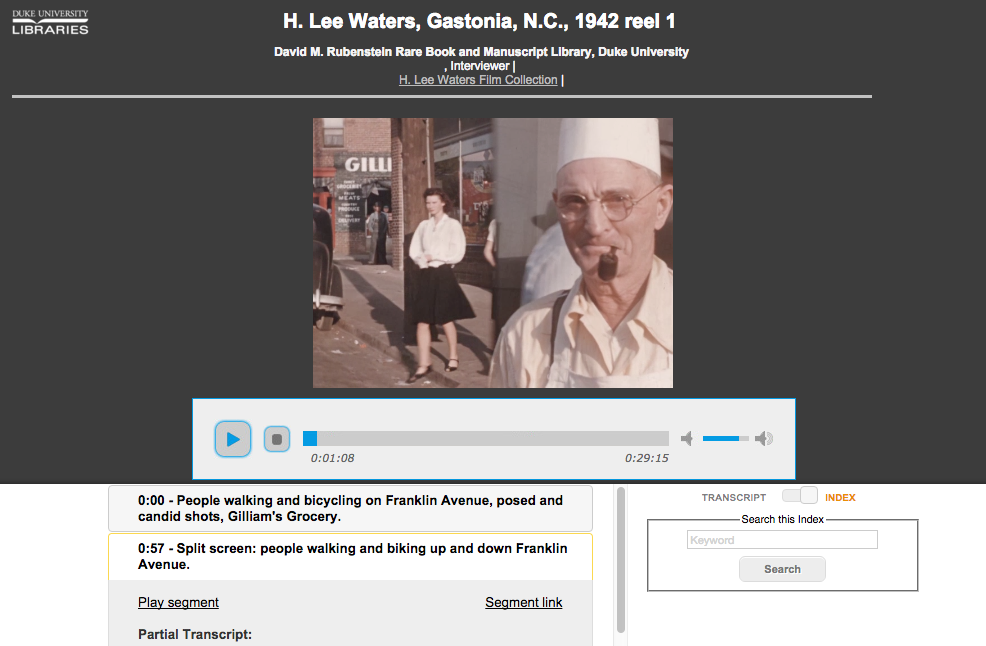

Our new digital collections (the ones in the Duke Digital Repository) have included a prominent link (under header “Source Collection”) from a digitized item to its source archival collection with some snippets of info from the collection guide presented in a popover. This was an important step toward connecting the dots, but still only gets someone to the top of the collection guide; from there, researchers are left on their own for figuring out where in the collection an item resides.

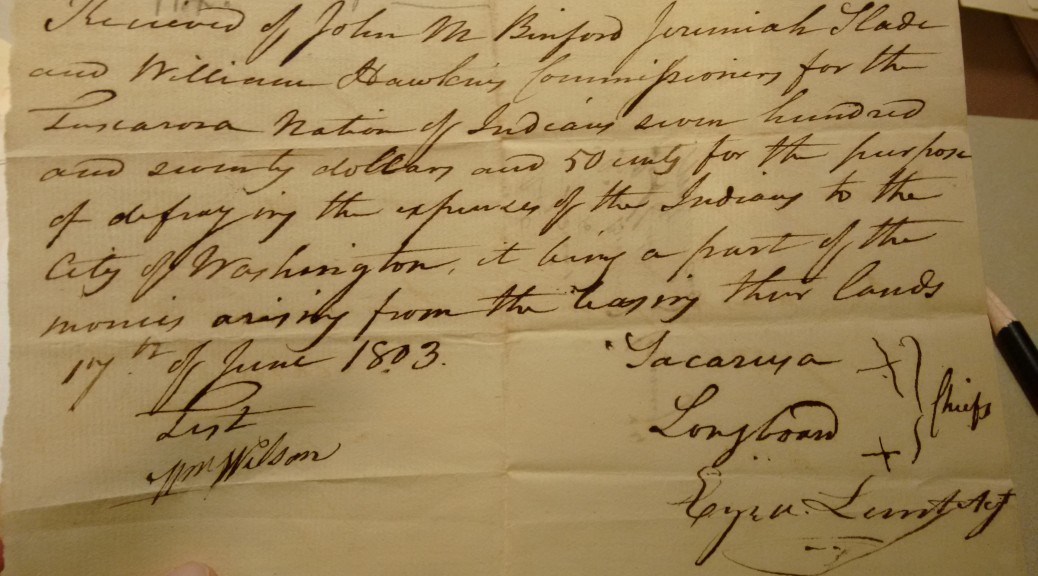

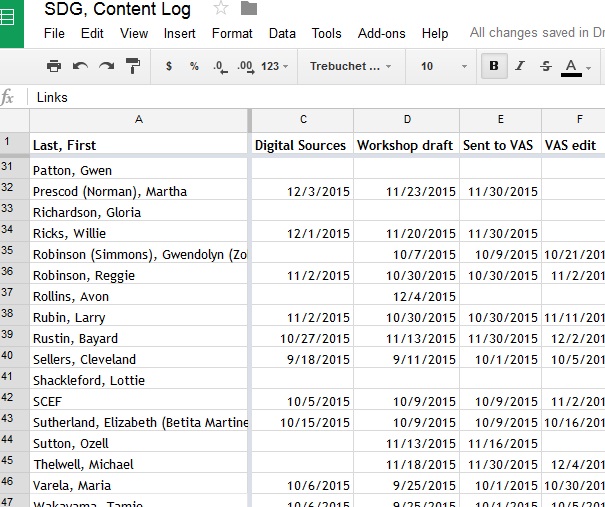

Beginning with this week’s newly-available Alex Harris Photographs Collection (and also the Benjamin & Julia Stockton Rush Papers Collection), we take it another step forward and present a deep link directly to the row in the collection guide that describes the item. For now, this link says “View Item in Context.”

This linkage is powered by indicating an ArchivesSpace ID in a digital object’s administrative metadata; it can be the ID for a series, subseries, folder, or item title, so we’re flexible in how granular the connection is between the digital object and its archival description.

Sticky Title & Series Info

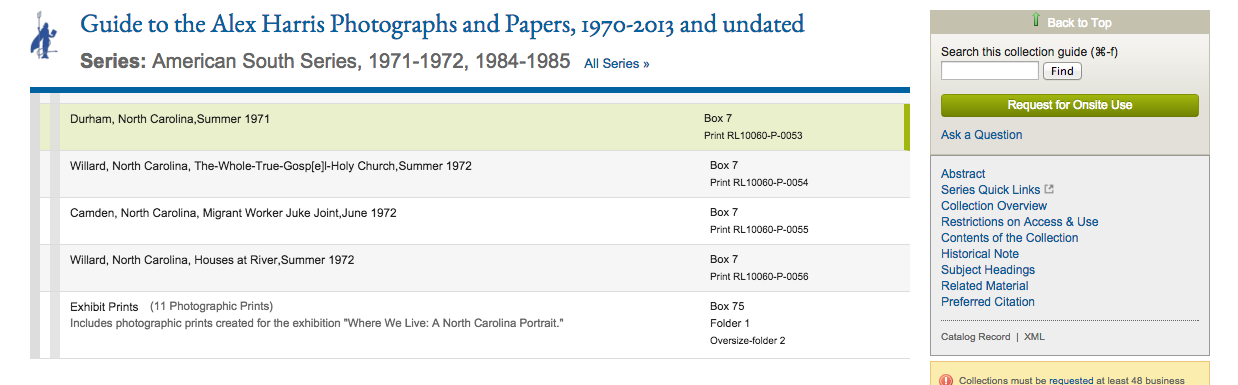

Our archival collection guides are currently rendered as single webpages broken into sections. Larger collections make for long webpages. Sometimes they’re really super long. Where the contents of the collection are listed, there’s a visual hierarchy in place with nested descriptions of series, subseries, etc. but it’s still difficult to navigate around and simultaneously understand what it is you’re viewing. The physical tedium of scrolling and the cognitive load required to connect related descriptive information located far away on a page make for bad usability.

As of last week, we now we keep the title of the collection “stuck” to the top of the screen once you’re no longer viewing the top of the page (it also functions as a link to get back to the top). And even more helpful is a new sticky series header that links to the beginning of the archival series within which the currently visible items were arranged; there’s usually an important description up there that helps contextualize the items listed below. This sticky header is context-aware, meaning it follows you around like a loyal companion, updating itself perpetually to reflect where you are as you navigate up or down.

This feature is powered via the excellent Bootstrap Scrollspy Javascript utility combined with some custom styling.

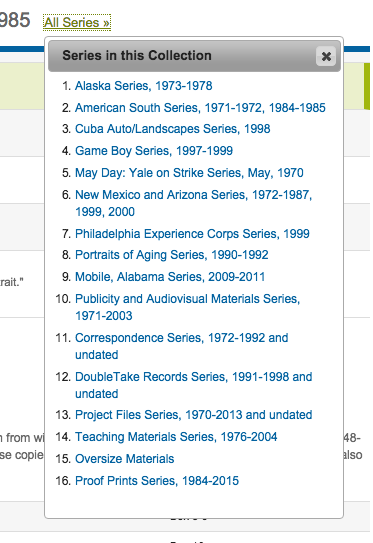

All Series Browser

To give researchers easier browsing between different archival series in a collection, we added a link in the sticky header to browse “All Series.” That link pops down a menu to jump directly to the start of each series within the collection guide.

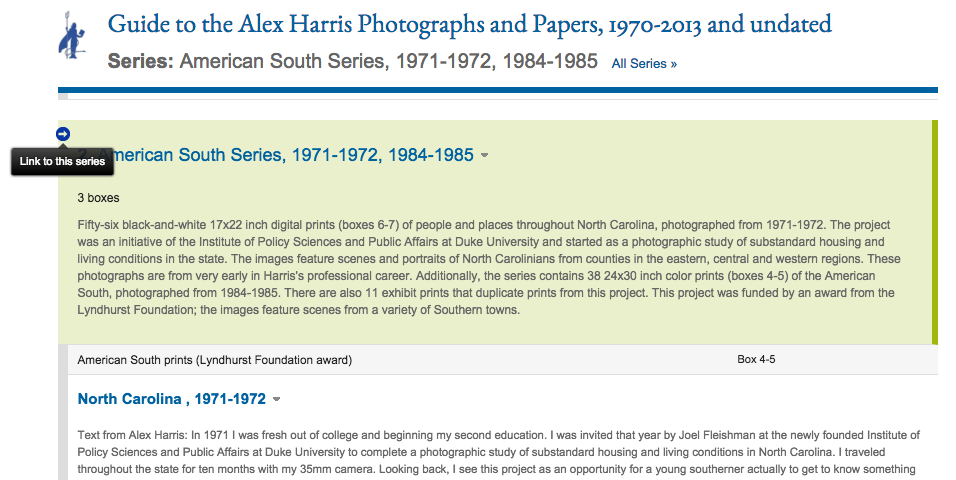

Direct Links to Anything

Researchers can now easily get a link to any row in a collection guide where the contents are described. This can be anything: a series, subseries, folder, or item. It’s simple—just mouseover the row, click the arrow that appears at the left, and copy the URL from the address bar. The row in the collection guide that’s the target of that link gets highlighted in green.

We would love to get feedback on these features to learn whether they’re helpful and see how we might enhance or adjust them going forward. Try them out and let us know what you think!

Special thanks to our metadata gurus Noah Huffman and Maggie Dickson for their contributions on these features.