At the recent Association of Moving Image Archivists conference in Portland, Oregon, I saw a lot of great presentations related to film and video preservation. As a Star Wars fan, I found one session particularly interesting. It was presented by Jimi Jones, a doctoral student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and is the result of his research into the world of fan edits.

This is a fairly modern phenomenon, whereby fans of a particular film, music recording or television show, often frustrated by the unavailability of that work on modern media, take it upon themselves to make it available, irrespective of copyright and/or the original creator’s wishes. Some fan edits appropriate the work, and alter it significantly, to make their own unique version. Neither Jimi Jones nor AMIA is advocating for fan edits, but merely exploring the sociological and technological implications they may have in the world of film and video digitization and preservation.

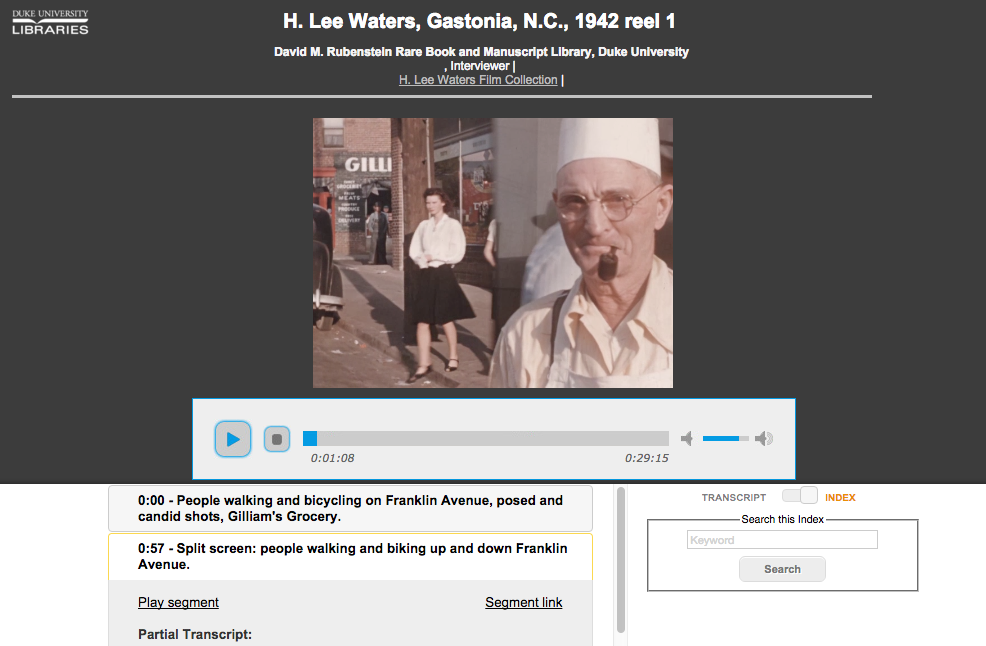

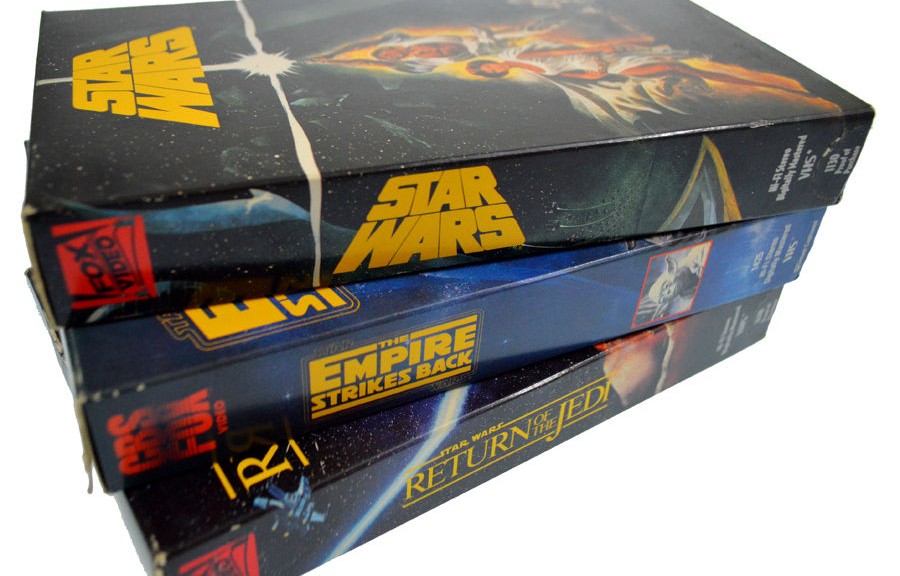

An example is the original 1977 theatrical release of “Star Wars” (later retitled Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope), a movie I spent my entire 1977 summer allowance on as a child, because I was so awestruck that I went back to my local theater to see it again and again. The version that I saw then, free of more recently superimposed CGI elements like Jabba The Hut, and the version in which Han Solo shoots Greedo in the Mos Eisley Cantina, before Greedo can shoot Solo, is not commercially available today via any modern high definition media such as Blu-Ray DVD or HD streaming.

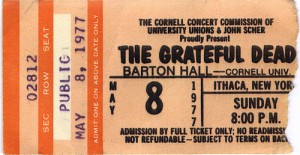

The last time most fans saw the original, unaltered Star Wars Trilogy, it was likely on VHS tape (as shown above). George Lucas, the creator of Star Wars, insists that his more recent “Special Editions” of the Star Wars Trilogy, with the added CGI and the more politically-correct, less trigger-happy Han Solo, are the “definitive” versions. Thus Lucas has refused to allow any other version to be legally distributed for at least the past decade. Many Star Wars fans, however, find this unacceptable, and they are striking back.

Armed with sophisticated video digitization and editing software, a network of Star Wars fans have collaborated to create “Star Wars: Despecialized Edition,” a composite of assorted pre-existing elements that accurately presents the 1977-1983 theatrical versions of the original Star Wars Trilogy in high definition for the first time. The project is led by an English teacher in Czechoslovakia, who goes by the name of “Harmy” online and is referred to as a “guerilla restorationist.” Using BitTorrent, and other peer-to-peer networks, fans can now download “Despecialized,” burn it to Blu-Ray, print out high-quality cover art, and watch it on their modern widescreen TV sets in high definition.

The fans, rightly or wrongly, claim these are the versions of the films they grew up with, and they have a right to see them, regardless of what George Lucas thinks. Personally, I never liked the changes Lucas later made to the original trilogy, and I agree that “Han Shot First,” or to paraphrase Johnny Cash, “I shot a man named Greedo, just to watch him die.” We all know Greedo was a scumbag who was about to kill Solo anyway, so Han’s preemptive shot in the original Star Wars makes perfect sense. I’m not endorsing piracy, but, as a fan, I certainly understand the pent-up demand for “Star Wars: Despecialized Edition.”

The psychology of nostalgia is interesting, particularly when fans desire something so intensely, they will go to great lengths, technologically, and otherwise, to satiate that need. Absence makes the heart, or fan, grow stronger. This is not unique to Star Wars. For instance, Neil Young, one of the best songwriters of his generation, released a major-label record in 1973 called “Time Fades Away,” which, to this day, has never been released on compact disc.

The album, recorded on tour while his biggest hit single, “Heart of Gold,” was topping the charts, is an abrupt shift in mood and approach, and the beginning of a darker, more desolate string of albums that fans refer to as “The Ditch Trilogy.” Regarding this period, Neil said: “Heart of Gold put me in the middle of the road. Traveling there soon became a bore, so I headed for the ditch. A rougher ride but I saw more interesting people there.” Many fans, myself included, regard the three records that comprise the ditch trilogy as his greatest achievement, due to their brutal honesty, and Neil’s absolute refusal to play it safe by coasting on his recent mainstream success. But for Neil, Time Fades Away brings up so many bad memories, particularly regarding the death of his guitarist, Danny Whitten, that he has long refused to release it on CD.

In 2005, Neil Young fans began gathering at least 14,000 petition signatures to get the album released on compact disc, but that yielded no results. So many took it upon themselves, using modern technology, to meticulously transfer mint-condition vinyl copies of “Time Fades Away” from their turntable to desktop computer using widely available professional audio software, and then burn the album to CD. Fans also scanned the original cover art from the vinyl record, and made compact disc covers and labels that closely approximate what it would look like if the CD had been officially released.

Other fans, using peer-to-peer networks, were able to locate a digital “test pressing” of the audio for a future CD release that was nixed by Neil before it went into production. Combining that test pressing audio, free of vinyl static, with professional artwork, the fans were essentially able to produce what Neil refused to allow, a pristine-sounding, and professionally-looking version of Time Fades Away on compact disc. Perhaps in response, Neil, has, just in the last year, allowed Time Fades Away to be released in digital form via his high-resolution 192.0kHz/24bit music service, Pono Music.

It’s clear that the main intent of the fans of Star Wars, Time Fades Away and other works of art is not to profit off their hybrid creations, or to anger the original creators. It’s merely to finally have access to what they are so nostalgic about. Ironically, if it wasn’t for the unavailability of these works, a lot of this community, creativity, software mastery and “guerrilla restoration” would not be taking place. There’s something about the fact that certain works are missing from the marketplace, that makes fans hunger for them, talk about them, obsess about them, and then find creative ways of acquiring or reproducing them.

This is the same impulse that fuels the fire of toy collectors, book collectors, garage-sale hunters and eBay bidders. It’s this feeling that you had something, or experienced something magical when you were younger, and no one has the right to alter it, or take access to it away from you, not even the person who created it. If you can just find it again, watch it, listen to it and hold it in your hands, you can recapture that youthful feeling, share it with others, and protect the work from oblivion. It seems like just yesterday that I was watching Han Solo shoot Greedo first on the big screen, but that was almost 40 years ago. “’Cause you know how time fades away.”

![The sun. (New York [N.Y.]), 21 July 1871. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.](https://blogs.library.duke.edu/bitstreams/files/2015/11/ny-sun-chronicling-america-1024x330.jpg)