Q: How is a silent H. Lee Waters film like an oral history recording?

A: Neither is text searchable.

But, leave it to oral historians to construct solutions for access to audiovisual resources of all stripes. No mistake, they’ve been thinking about it for a long time. Purposefully, profoundly non-textual at their creation, oral histories have since their postwar genesis contended with a central irony: as research they are exploited almost exclusively via textual transcription. Oral histories that don’t get transcribed get, instead, infamously ignored. So as the online floodgates have opened and digital media recorders and players have kept pace, oral historians have seen an opportunity to grapple meaningfully with closing the gap between the text and its source, and perhaps at the same time free the interview from the expectation that it should be transcribed.

Enter OHMS (http://www.oralhistoryonline.org/). In 2013, Doug Boyd at the University of Kentucky debuted the results of an IMLS-funded project to create the Oral History Metadata Synchronizer. A free, open-source tool, OHMS empowers even the smallest oral history archive to encode its media with textual information. The OHMS editor enables the oral historian to easily create item level metadata for an oral history recording, including an index or subject list that can drop a researcher into an interview at that selected point. OHMS can also timestamp an existing transcript, so that researchers can track the audio via the text. In its short life, OHMS has demonstrated a way to bridge the great divide among oral history theorists, which reads something like this: Should our focus be the audio or the transcript?

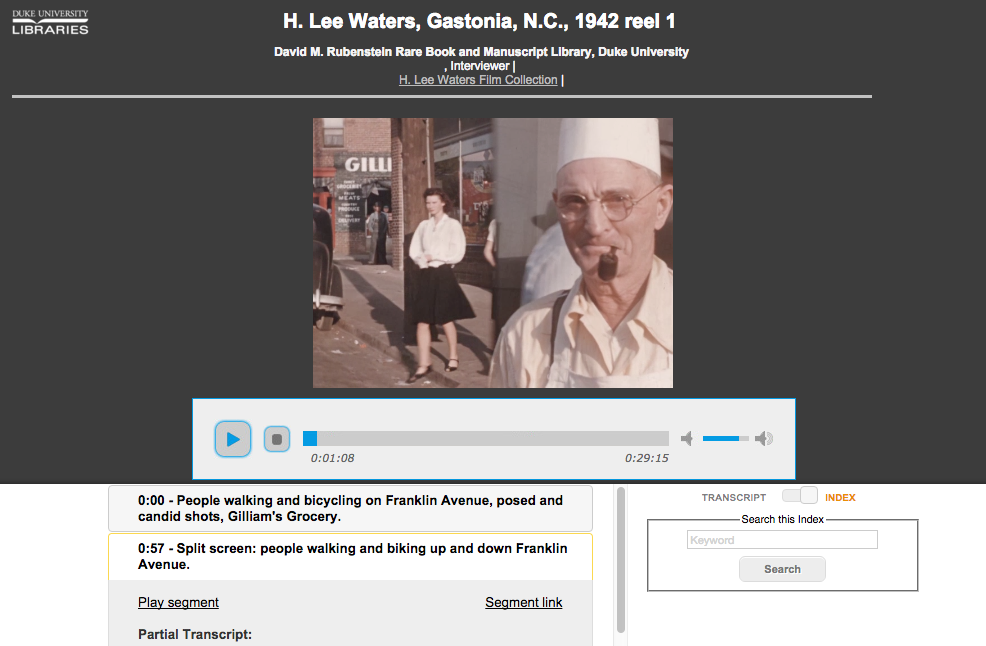

While it springs from the minds of oral historians, OHMS might more accurately be termed the Media Metadata Synchronizer. When I saw Doug’s presentation on OHMS at the Oral History Association meeting in 2013, two alternative uses immediately came to mind: OHMS had the potential to help us provide bilingual entry to the 3,500+ recordings in our Radio Haiti Collection (currently being digitzed), and it could dramatically enhance access to one of Duke’s great collections, the H. Lee Waters Films. Waters filmed his Movies of Local People in mostly smaller communities around North Carolina from 1936-1942, using silent reversal film stock. Waters’ effort to supplement his family’s income has over the intervening years become a major historical document of the state during the Great Depression. And yet as rich as the collection is, it is difficult for students, scholars, and filmmakers to find specific scenes or subjects among the thousands of two-second shots Waters put to film. Several years ago, an intern in the archive created shotlists for some of the films, but these existed independently of the films and were not terribly accurate in matching times since they were created using VHS tapes (and VHS players are notorious for displaying incorrect times). OHMS would give us the opportunity to update the shotlists we had and create some new ones, linking description to precise points within the films.

Implementing OHMS at Duke Libraries was a pleasure, mostly because I had the opportunity to work with my colleagues in Digital Projects and Production Services, an outstanding team that can do amazing things with our equally amazing archival resources. Recognizing the open-source spirit of OHMS, Sean Aery, Will Sexton, and Molly Bragg immediately saw how the system could help us get deeper into the Waters films without having to build out a complex infrastructure (or lay out lots of cash). And so, when the H. Lee Waters website went live last year with 35 hours of mostly undescribed digital video (although we did post those older shotlists too, where we had them), it was generally agreed that a phase two would happen sooner rather than later and include a pilot for OHMS shotlists. Rubenstein Audiovisual Intern Olivia Carteaux worked diligently through the spring to normalize existing shotlists and create new ones where possible. This necessitated breaking down the descriptive data we had into spreadsheets, so we could then “crosswalk” the description into the OHMS xml file that is at the heart of the system.

While the OHMS index viewer allows for metadata including title or description, partial transcript, segment synopsis, keywords, subjects, GPS coordinates and a link to a map, we concentrated on providing a descriptive sentence as the title and, where it was easy to find, the location of the action.

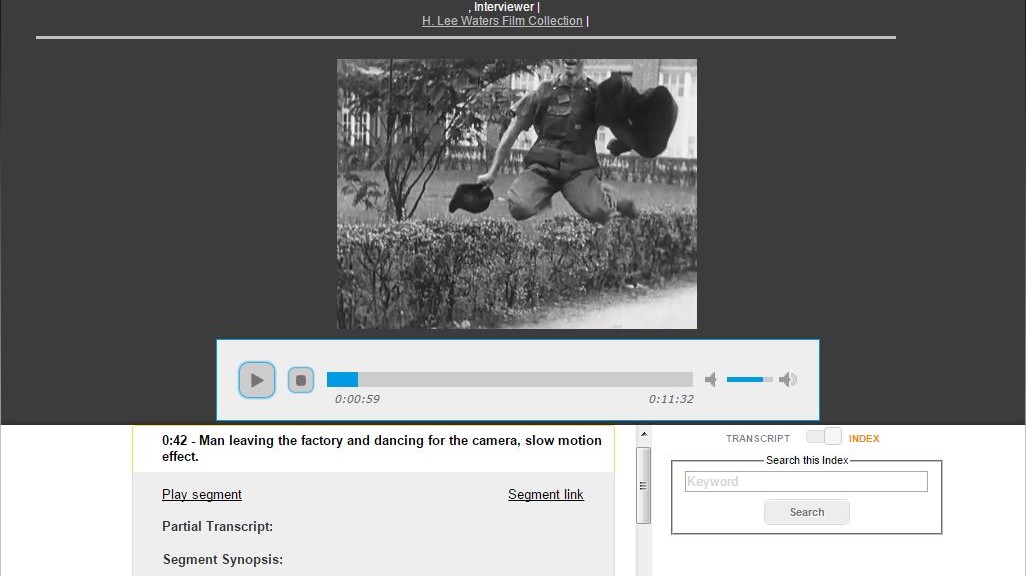

While on the face of it generating description for the H. Lee Waters films might seem fairly straightforward, we found a number of challenges in describing his silent moving images. For starters, given Waters’ quick edits, what would adequate frequency of description look like? A new descriptive entry at every cut would be extremely unwieldy. At the same time we recognized that without a spoken or textual counterpart to the image, every time we chose not to describe would deprive potential users of a “way in.” We settled on creating entries whenever the general scene or action changed; for instance, when Waters shifts from a scene on main street to one in front of a mill or school, or within the scene at a school when the action goes from schoolyard play to the pledge of allegiance. Sometimes the shifts are obvious, other times they are more subtle, so watching the action with a deep focus is necessary. We also created new entries whenever Waters created a trick shot, such as a split screen, a speed up or slow down of the action, a reverse shot, or a masking shot. Additionally, storefront signs, buildings, and landmarks also became good places to create entries, depending on their prominence; for these, too, we attempted to create GPS coordinates where we could easily do so.

Our second challenge was how much to invest in each description. “A picture is worth a thousand words” and “every picture tells a story” sum up much of the Waters footage, but brevity was of value to the workflow. One sentence, which did not have to be properly complete — a sort of descriptive bullet point — was decided on as our rule of thumb. In the next phase of this process I hope to use the keywords field more effectively, but that requires a controlled vocabulary, which brings me to our third challenge: normalizing description was the most difficult single piece of describing the films. Turns out there’s not a lot of library-based methodology for describing moving images, although there are general recommended approaches for describing images for the visually impaired. Then, of course, there’s the difficulty in deciding how to represent nuanced factors such as race, ethnicity, class, and gender. It is clear that in the event we undertake to create shotlists for all the Waters films, the first order of business will be to create a thesaurus of terms, to provide consistent description across the films.

When we felt like we had enough transformed shotlists for a pilot OHMS project for the Waters website, the OHMS player was loaded onto a server and the playlists uploaded. Links to the 29 shotlists were then placed below the video windows on their respective pages. To access the video and synchronized description, simply click on the link that says “Synchronized Shot List.” In this initial run we’re hoping to upload about 20 more shotlists, and at that point take a breath and see how we can improve on what we’ve accomplished. Given the challenges of presenting audiovisual resources online, there’s never really a “done,” only steady improvement. OHMS has provided what I believe is a clear step forward on access to the Waters films, and has the potential to help us transform other audiovisual collections into deeply mined treasures of the archive.

Post contributed by Craig Breaden, Audiovisual Archivist, Rubenstein Library