Before you let your eyes glaze over at the thought of metadata, let me familiarize you with the term and its invaluable role in the creation of the library’s online Digital Collections. Yes, metadata is a rather jargony word librarians and archivists find themselves using frequently in the digital age, but it’s not as complex as you may think. In the most simplistic terms, the Society of American Archivists defines metadata as “data about data.” Okay, what does that mean? According to the good ol’ trusty Oxford English Dictionary, it is “data that describes and gives information about other data.” In other words, if you have a digitized photographic image (data), you will also have words to describe the image (metadata).

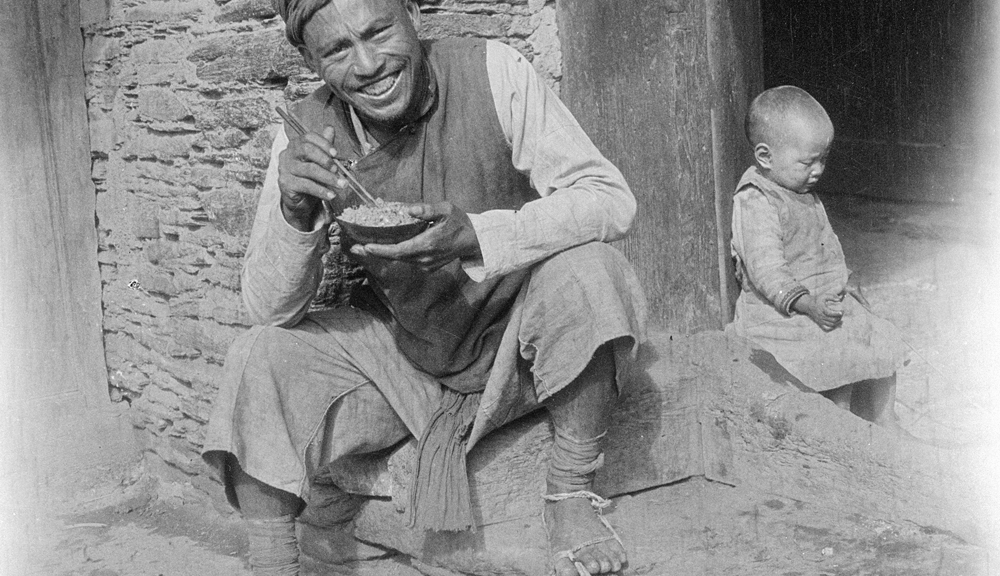

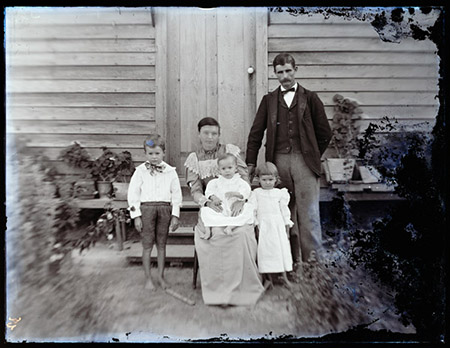

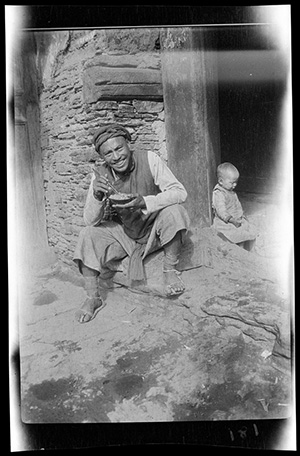

Better yet, think of it this way. If that image were of a large family gathering and grandma lovingly wrote the date and names of all the people on the backside, that is basic metadata. Without that information those people and the image would suddenly have less meaning, especially if you have no clue who those faces are in that family photo. It is the same with digital projects. Without descriptive metadata, the items we digitize would hold less meaning and prove less valuable for researchers, or at least be less searchable. The better and more thorough the metadata, the more it promotes discovery in search engines. (Check out the metadata from this Cornett family photo from the William Gedney collection.)

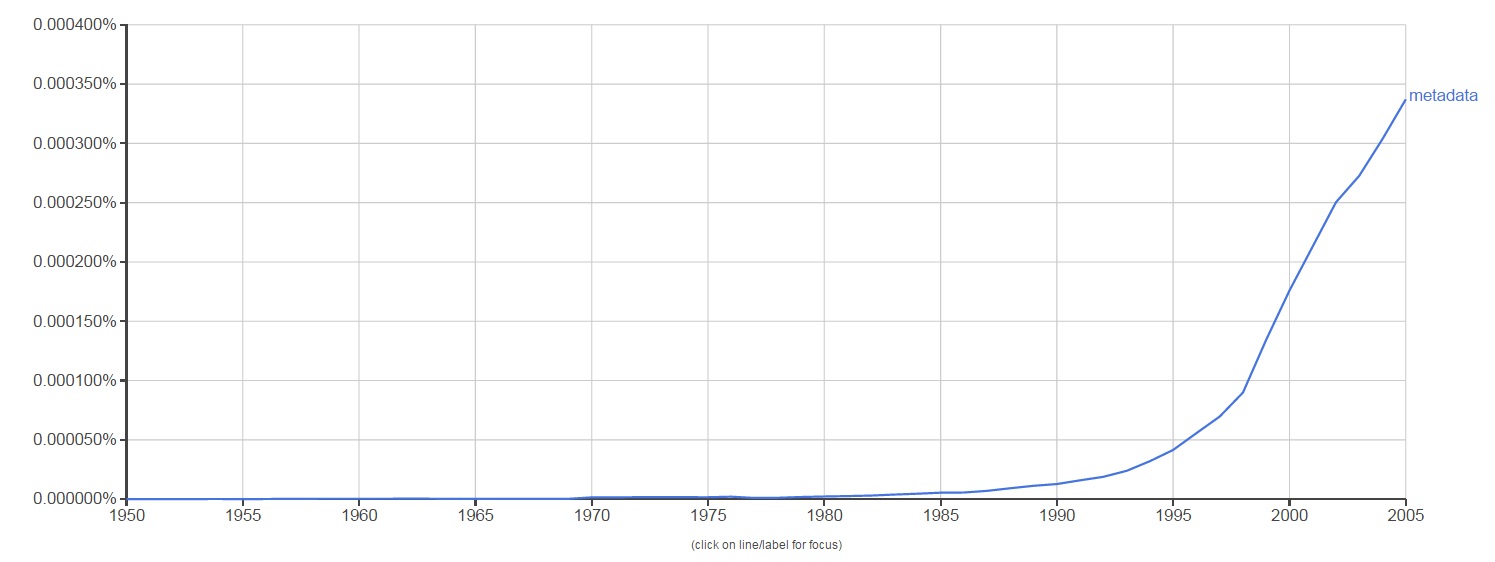

The term metadata was first used in the late 1960s in computer programming language. With the advent of computing technology and the overabundance of digital data, metadata became a key element to help describe and retrieve information in an automated way. The use of the word metadata in literature over the last 45 years shows a steeper increase from 1995 to 2005, which makes sense. The term became used more and more as technology grew more widespread. This is reflected in the graph below from Google’s Ngram Viewer, which scours over 5 million Google Books to track the usage of words and phrases over time.

Because of its link with computer technology, metadata is widely used in a variety of fields that range from computer science to the music industry. Even your music playlist is full of descriptive metadata that relates to each song, like the artist, album, song title, and length of audio recording. So, libraries and archives are not alone in their reliance on metadata. Generating metadata is an invaluable step in the process of preserving and documenting the library’s unique collections. It is especially important here at the Digital Production Center (DPC) where the digitization of these collections happens. To better understand exactly how important a role metadata plays in our job, let’s walk through the metadata life cycle of one of our digital projects, the Duke Chapel Recordings.

The Chapel Recordings project consists of digitizing over 1,000 cassette and VHS tapes of sermons and over 1,300 written sermons that were given at the Duke Chapel from the 1950s to 2000s. These recordings and sermons will be added to the existing Duke Chapel Recordings collection online. Funded by a grant from the Lilly Foundation, this digital collection will be a great asset to Duke’s Divinity School and those interested in hermeneutics worldwide.

Before the scanners and audio capture devices are even warmed up at the DPC, preliminary metadata is collected from the analog archival material. Depending on the project, this metadata is created either by an outside collaborator or in-house at the DPC. For example, the Duke Chronicle metadata is created in-house by pulling data from each issue, like the date, volume, and issue number. I am currently working on compiling the pre-digitization metadata for the 1950s Chronicle, and the spreadsheet looks like this:

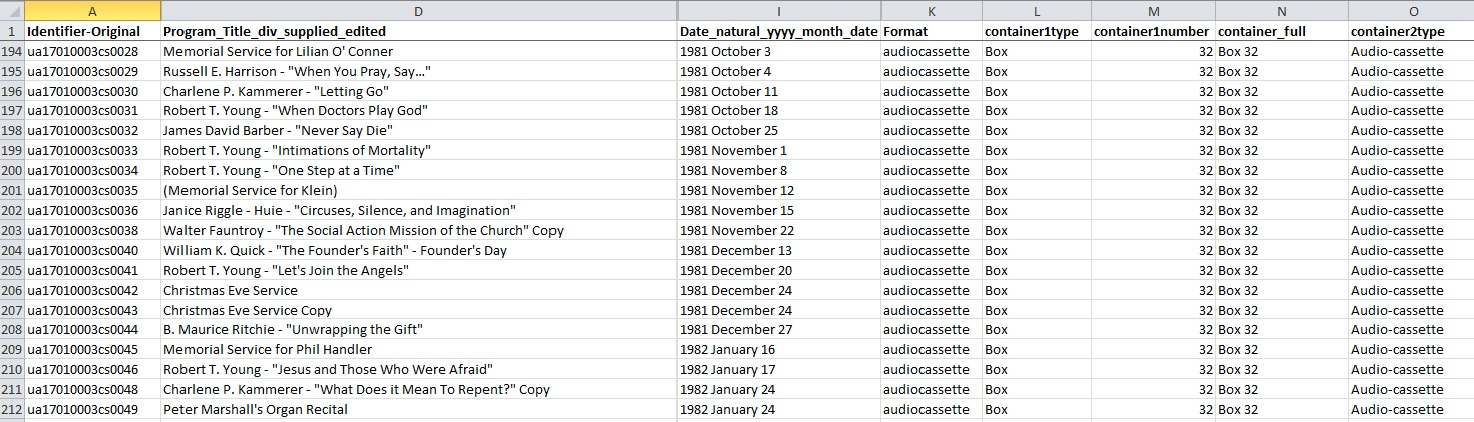

As for the Chapel Recordings project, the DPC received an inventory from the University Archives in the form of an Excel spreadsheet. This inventory contained the preliminary metadata already generated for the collection, which is also used in Rubenstein Library‘s online collection guide.

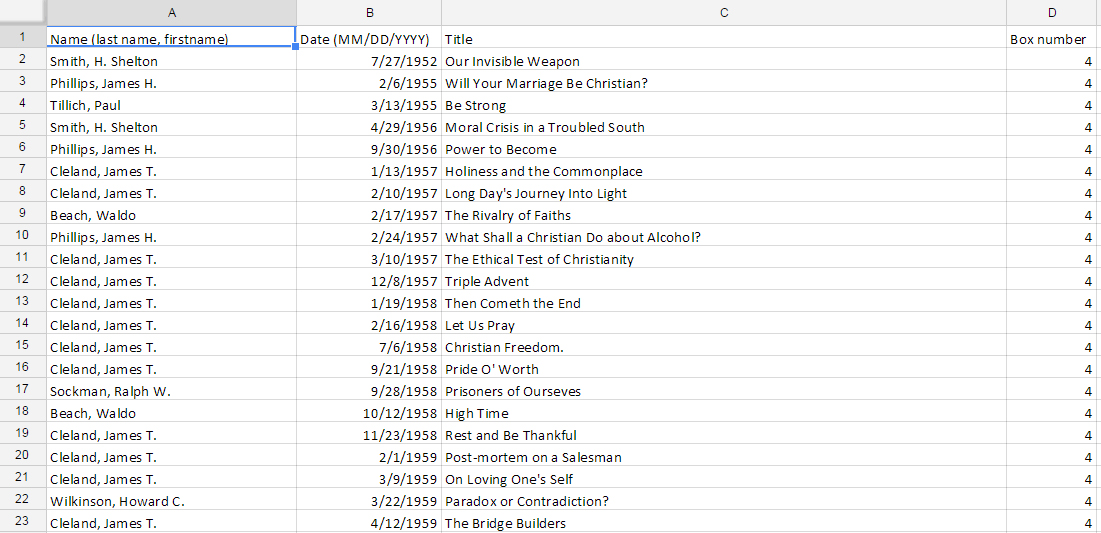

The University Archives also supplied the DPC with an inventory of the sermon transcripts containing basic metadata compiled by a student.

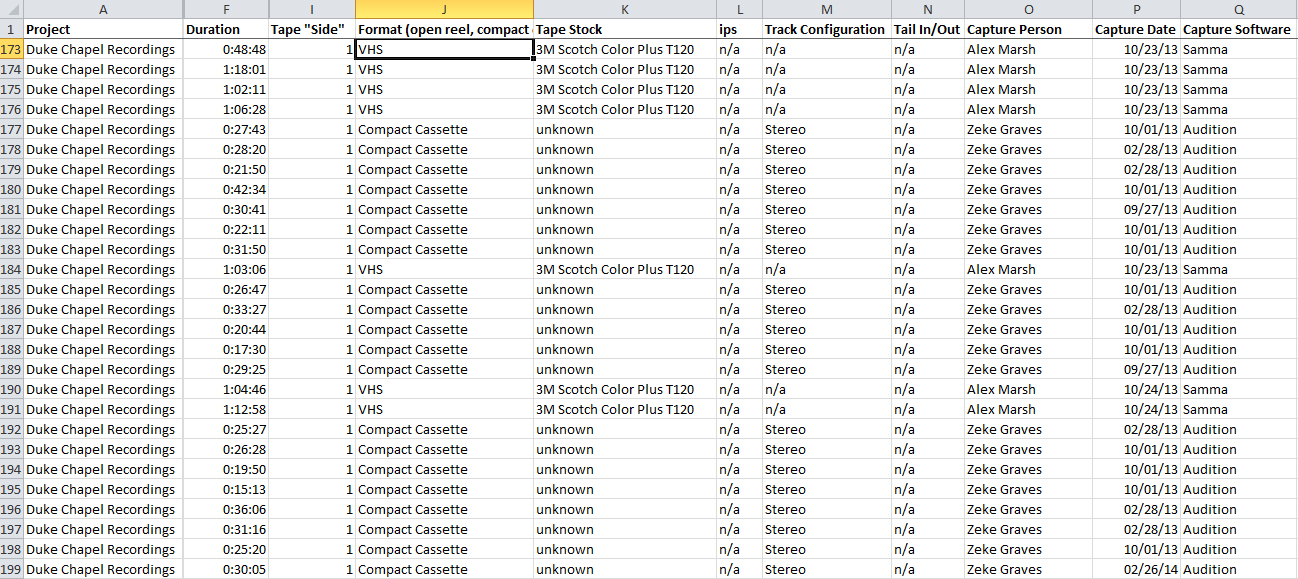

Here at the DPC, we convert this preliminary metadata into a digitization guide, which is a fancy term for yet another Excel spreadsheet. Each digital project receives its own digitization guide (we like to call them digguides) which keeps all the valuable information for each item in one place. It acts as a central location for data entry, but also as a reference guide for the digitization process. Depending on the format of the material being digitized (image, audio, video, etc.), the digitization guide will need different categories. We then add these new categories as columns in the original inventory spreadsheet and it becomes a working document where we plug in our own metadata generated in the digitization process. For the Chapel Recordings audio and video, the metadata created looks like this:

Once we have digitized the items, we then run the recordings through several rounds of quality control. This generates even more metadata which is, again, added to the digitization guide. As the Chapel Recordings have not gone through quality control yet, here is a look at the quality control data for the 1980s Duke Chronicle:

Once the digitization and quality control is completed, the DPC then sends the digitization guide filled with metadata to the metadata archivist, Noah Huffman. Noah then makes further adds, edits, and deletes to match the spreadsheet metadata fields to fields accepted by the management software, CONTENTdm. During the process of ingesting all the content into the software, CONTENTdm links the digitized items to their corresponding metadata from the Excel spreadsheet. This is in preparation for placing the material online. For even more metadata adventures, see Noah’s most recent Bitstreams post.

In the final stage of the process, the compiled metadata and digitized items are published online at our Digital Collections website. You, the researcher, history fanatic, or Sunday browser, see the results of all this work on the page of each digital item online. This metadata is what makes your search results productive, and if we’ve done our job right, the digitized items will be easily discovered. The Chapel Recordings metadata looks like this once published online:

Further down the road, the Duke Divinity School wishes to enhance the current metadata to provide keyword searches within the Chapel Recordings audio and video. This will allow researchers to jump to specific sections of the recordings and find the exact content they are looking for. The additional metadata will greatly improve the user experience by making it easier to search within the content of the recordings, and will add value to the digital collection.

On this journey through the metadata life cycle, I hope you have been convinced that metadata is a key element in the digitization process. From preliminary inventories, to digitization and quality control, to uploading the material online, metadata has a big job to do. At each step, it forms the link between a digitized item and how we know what that item is. The life cycle of metadata in our digital projects at the DPC is sometimes long and tiring. But, each stage of the process creates and utilizes the metadata in varied and important ways. Ultimately, all this arduous work pays off when a researcher in our digital collections hits gold.

While I’m glad not to be living in a Tony Scott movie, on occasion I feel like Bruce Willis’ character near the beginning of “The Last Boy Scout.” Just look at some of the things they say about us.

While I’m glad not to be living in a Tony Scott movie, on occasion I feel like Bruce Willis’ character near the beginning of “The Last Boy Scout.” Just look at some of the things they say about us.