One of my favorite movies as a youngster was Steven Spielberg’s “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” It’s non-stop action as the adventurous Indiana Jones criss-crosses the globe in an exciting yet dangerous race against the Nazis for possession of the Ark of the Covenant. According to the Book of Exodus, the Ark is a golden chest which contains the original stone tablets on which the Ten Commandments are inscribed, the moral foundation for both Judiasm and Christianity. The Ark is so powerful that it single-handedly destroys the Nazis and then turns Steven Spielberg and Harrison Ford into billionaires. Countless sequels, TV shows, theme-park rides and merchandise follow.

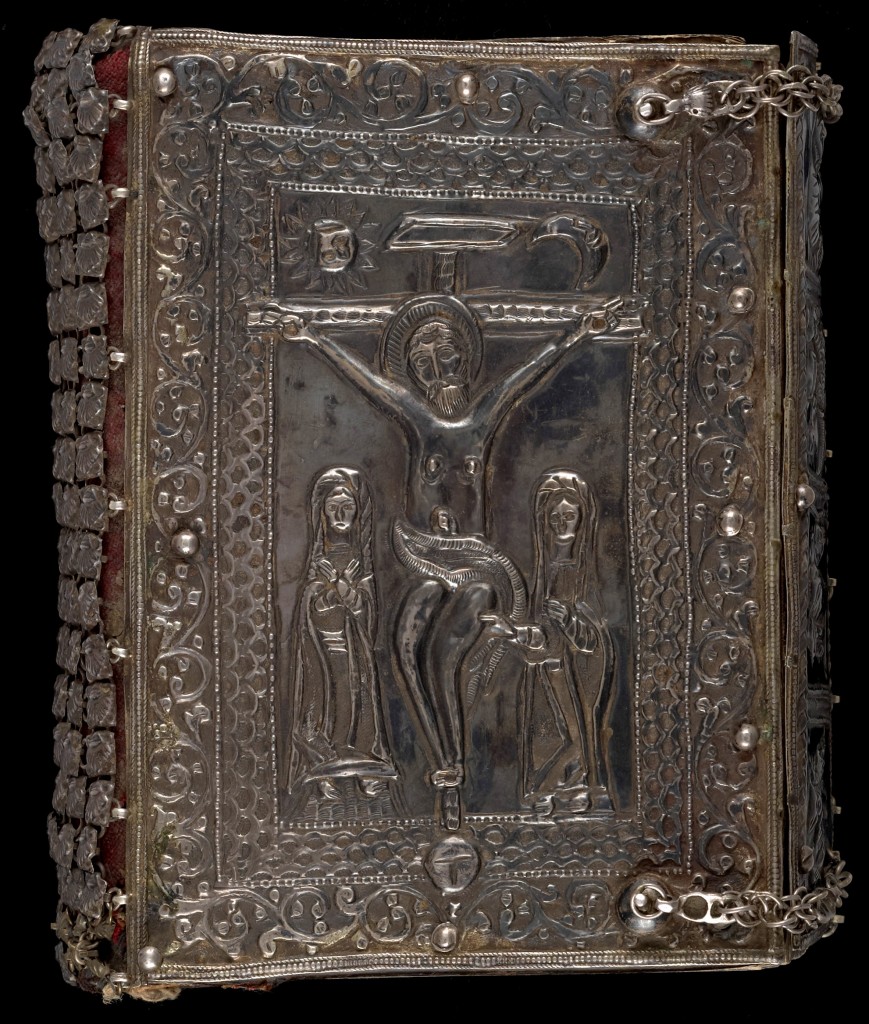

Fast-forward several decades, and I am asked to digitize Duke Libraries’ Kenneth Willis Clark Collection of Greek Manuscripts. Although not quite as old as the Ten Commandments, this is an amazing collection of biblical texts dating all the way back to the 9th century. These are weighty volumes, hand-written using ancient inks, often on animal-skin parchment. The bindings are characterized as Byzantine, and often covered in leathers like goatskin, sometimes with additional metal ornamentation. Although I have not had to run from giant boulders, or navigate a pit of snakes, I do feel a bit like Indiana Jones when holding one of these rare, ancient texts in my hands. I’m sure one of these books must house a secret code that can bestow fame and fortune, in addition to the obvious eternal salvation.

Before digitization, Senior Conservator Erin Hammeke evaluates the condition of each Greek manuscript, and rules out any that are deemed too fragile to digitize. Some are considered sturdy enough, but still need repairs, so Erin makes the necessary fixes. Once a manuscript is given the green light for digitization, I carefully place it in our book cradle so that it cannot be opened beyond a 90-degree angle. This helps protect our fragile bound materials from unnecessary stress on the binding. Next, the aperture, exposure, and focus are carefully adjusted on our Phase One P65+ digital camera so that the numerical values of our X-rite color calibration target, placed on top of the manuscript, match the numerical readings shown on our calibrated monitors.

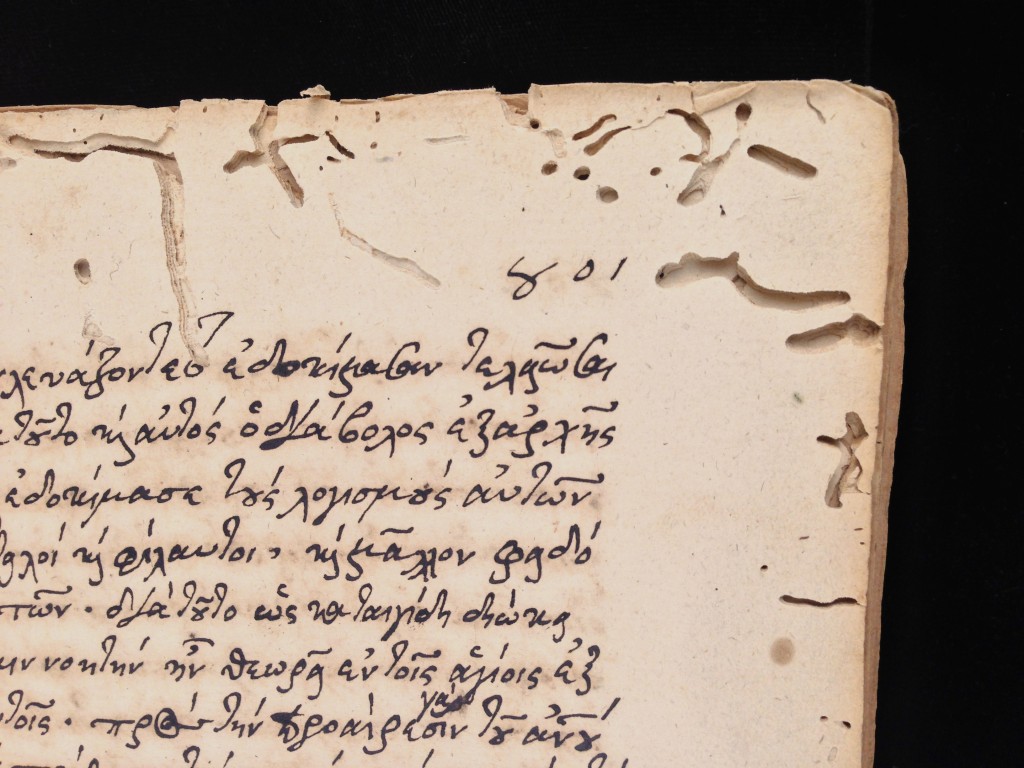

As the photography begins, each page of the manuscript is carefully turned by hand, so that a new image can be made of the following page. This is a tedious process, but requires careful concentration so the pages are consistently captured throughout each volume. Right-hand (recto) pages are captured first, in succession. Then the volume is turned over, so that the left-hand (verso) pages can be captured. I can’t read Greek, but it’s fascinating to see the beauty of the calligraphy, and view the occasional illustrations that appear on some pages. Sometimes, I discover that moths, beetles or termites have bored through the pages over time. It’s interesting to speculate as to which century this invasive destruction may have occurred. Perhaps the Nazis from the Indiana Jones movies traveled back in time, and placed the insects there?

Once the photography is complete, the recto and verso images are processed and then interleaved to recreate the left-right page order of the original manuscript. Next, the images go through a quality-control process in which any extraneous background area is cropped out, and each page is checked for clarity and consistent color and illumination. After that, another round of quality control insures that no pages are missing, or out of order. Finally, the images are converted to Pyramid TIFF files, which allow our web site users to zoom out and see all the pages at once, or zoom in to see maximum detail of any selected page. 38 Greek manuscripts are ready for online viewing now, and many more are coming soon. Stay tuned for the exciting sequel: “Indiana Jones and Even More Greek Manuscripts.”