Featured image – Wayback Machine capture of the Tripod2 beta site in February, 2011.

We all design and create platforms that work beautifully for us, that fill us with pride as they expand and grow to meet our programmatic needs, and all the while the world changes around us, the programs scale beyond what we envisioned, and what was once perfectly adaptable becomes unsustainable, appearing to us all of the sudden as a voracious, angry beast, threatening to consume us, or else a rickety contraption, teetering on the verge of a disastrous collapse. I mean, everyone has that experience, right?

In March of 2011, a small team consisting primarily of me and fellow developer Sean Aery rolled out a new, homegrown platform, Tripod2. It became the primary point of access for Duke Digital Collections, the Rubenstein Library’s collection guides, and a handful of metadata-only datasets describing special collections materials. Within a few years, we had already begun talking about migrating all the Tripod2 stuff to new platforms. Yet nearly a decade after its rollout, we still have important content that depends on that platform for access.

Nevertheless, we have made significant progress. Sunsetting Tripod2 became a priority for one of the teams in our Digital Preservation and Publishing Program last year, and we vowed to follow through by the end of 2020. We may not make that target, but we do have firm plans for the remaining work. The migration of digital collections to the Duke Digital Repository has been steady, and nears its completion. This past summer, we rolled out a new platform for the Rubenstein collection guides, based on the ArcLight framework. And now have a plan to handle the remaining instances of metadata-only databases, a plan that itself relies on the new collection guides platform.

We built Tripod2 on the triptych of Python/Django, Solr, and a document base of METS files. There were many areas of functionality that we never completely developed, but it gave us a range of capability that was crucial in our thinking about digital collections a decade ago – the ability to customize, to support new content types, and to highlight what made each digital collection unique. In fact, the earliest public statement that I can find revealing the existence of Tripod2 is Sean’s blog post, “An increasingly diverse range of formats,” from almost exactly ten years ago. As Sean wrote then, “dealing with format complexity is one of our biggest challenges.”

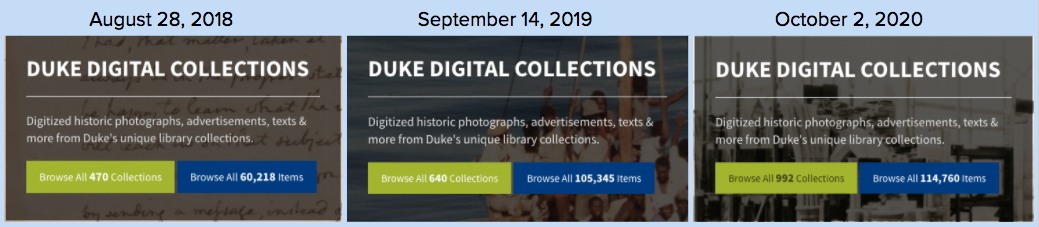

As the years went by, a number of factors made it difficult to keep Tripod2 current with the scope of our programs and the changing of web technology. The single most prevalent factor was the expanding scope of the Duke Digital Collections program, which began to take on more high-volume digitization efforts. We started adding all of our new digital collections to the Duke Digital Repository (DDR) starting in 2015, and the effort to migrate from Tripod2 to the repository picked up soon thereafter. That work was subject to all sorts of comical and embarrassing misestimations by myself on the pages of this very blog over the years, but thanks to the excellent work by Digital Collections and Curation Services, we are down to the final stages.

Moving digital collections to the DDR went hand-in-hand with far less customization, and far less developer intervention to publish a new collection. Where we used to have developers dedicated to individual platforms, we now work together more broadly as a team, and promote redundancy in our development and support models as much as we can. In both our digital collections program and our approach to software development, we are more efficient and more process-driven.

Given my record of predictions about our work on this blog, I don’t want to be too forward in announcing this transition. We all know that 2020 doesn’t suffer fools gladly, or maybe it suffers some of them but not others, and maybe I shouldn’t talk about 2020 just like this, right out in the open, where 2020 can hear me. So I’ll just leave it here – in recent times, we have done a lot of work toward saying goodbye to Tripod2. Perhaps soon we shall.