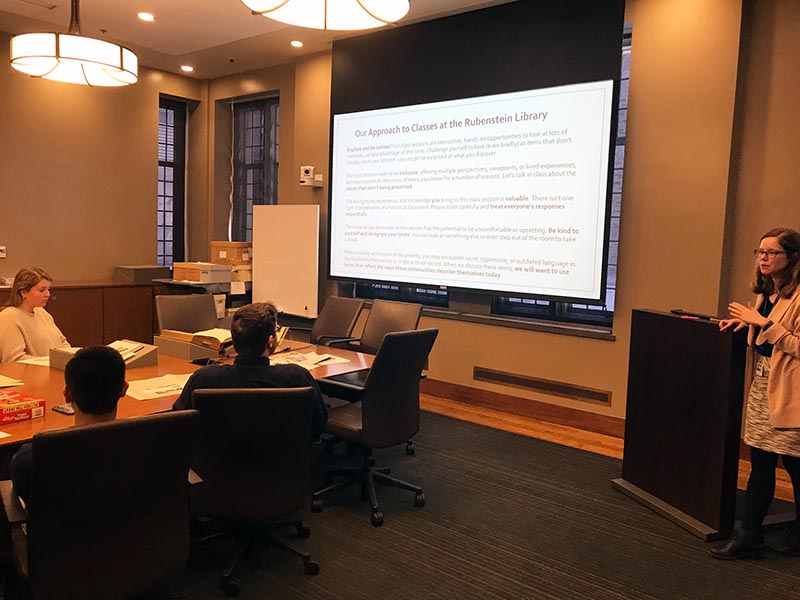

Post contributed by Brooke Guthrie, Research Services Librarian.

A few days ago, I went searching (in the catalog) for the perfect Thanksgiving-related item and came across a folder titled “Turkey Test, 1951-1952” in the papers of Theodore “Ted” Minah. What kind of test could Minah, the Director of Duke University Dining Halls from 1946 to 1974, be conducting on turkeys? Was it a taste test or some sort of “mystery meat” challenge? Was he investigating the sleep-inducing properties of turkey meat? Was he out to prove that turkeys really are as dumb as they are rumored to be?

Sadly (for us), Minah was a practical fellow and it was none of those things. Minah, who worked hard to provide quality food at the lowest price to the university, wanted to know if turkey could be a cost effective meat option for campus dining halls. The test was part of an effort by the National Turkey Federation (NTF), an organization representing turkey farmers and processors, to better market the turkey and get more turkey on more American tables. (The NTF is also the organization that provides turkeys for the annual White House turkey pardon.)

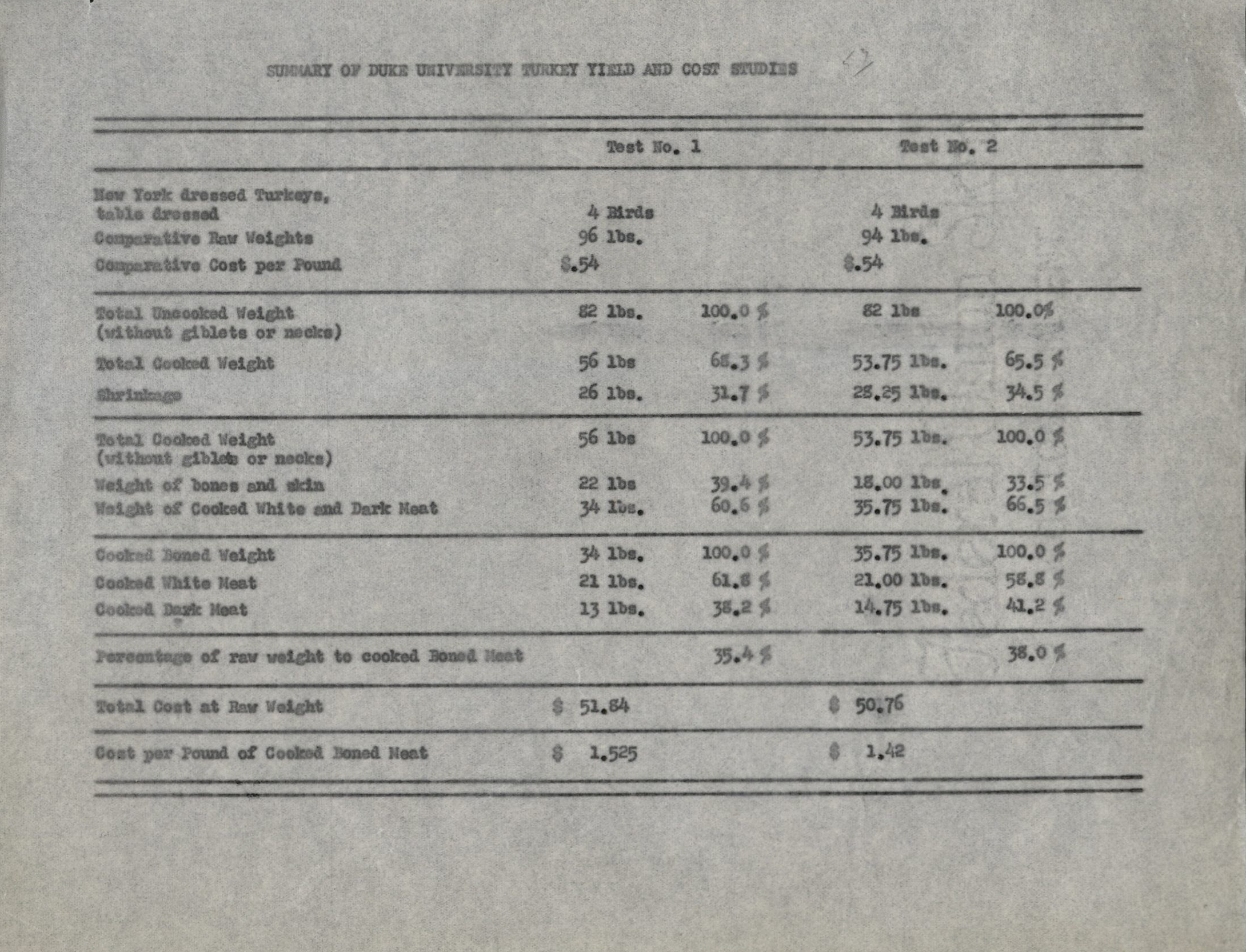

Duke, along with dining offices at other schools, participated in a 1951 study to determine how much edible meat a cooked turkey yielded and how much a single serving of turkey would cost. Led by Food Production Manager Majorie Knapp, Duke cooked several whole turkeys and took detailed measurements before and after cooking. Duke’s test used Broad Breasted Bronze turkeys from Sampson County, North Carolina which, according to Minah, “is a delicious eating turkey.”

According to the results of the Duke test, turkey would cost around $1.50 per pound of cooked meat and around $0.20 per serving. In her summary, Knapp noted that the price for chicken was cheaper at $1.37 per pound. A serving of chicken would be a few cents cheaper than turkey.

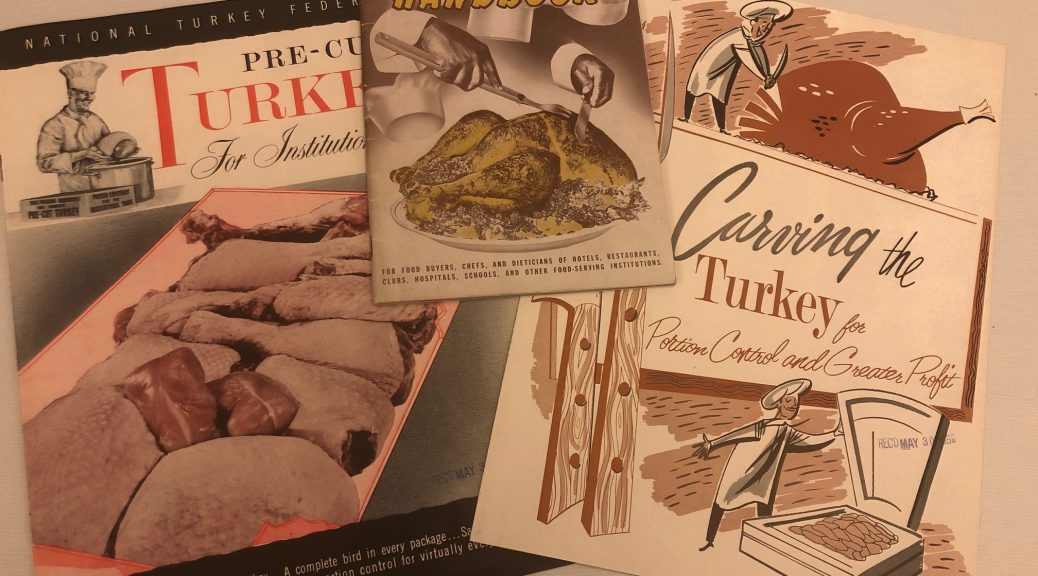

The test results were submitted and later included in NTF marketing materials designed to get turkey on the menu at places like schools, hotels, and hospitals. In addition to the study results and Ted Minah’s correspondence about the study, the “Turkey Test” folder also includes a few of these industry publications.

The booklets and brochures, with catchy titles like “Carving the Turkey for Portion Control and Greater Profit” and “Pre-Cut Turkeys for Institutional Use,” mostly contain recipes and instructions for properly cooking a turkey. The recipes were certainly creative. Creamed Turkey in Pastry Tart, Turkey Salad Roll, and Turkey Chow Mein on Chinese Noodles (to name just a few) were suggested as “profit-making turkey dishes.”

If you are desperately seeking things to do with all of those turkey leftovers, the NTF has your back. You could make a Jellied Turkey Salad, put some gibblets on toast, or impress your guests with jellied turkey feet. They even provide tips on what to do with the carcass!

The Ted Minah materials include one more turkey item worth mentioning. He was sent a booklet of photos showing turkeys frolicking on a farm. It includes a photo of a turkey that doesn’t seem particularly pleased to have his photo taken for the purposes of marketing his own deliciousness as food.

If your uncle brings up politics at Thanksgiving dinner, just turn the conversation toward the fun facts you learned in this blog post and then you can all bond over your love of jellied turkey feet.

Happy Thanksgiving!

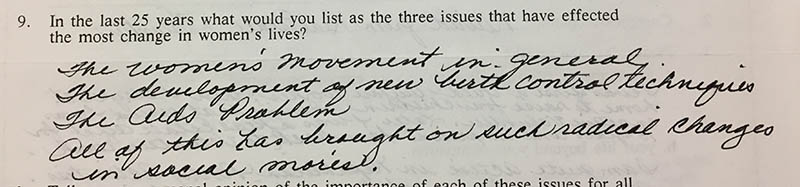

![Typed section of the 1964 Freshman Handbook Exam: "6. What procedure would a student [follow] if she wishes her brother to carry her record player to her room?"](http://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2019/08/question6.jpg)

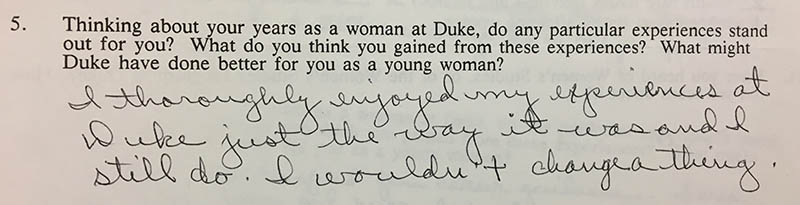

![Question 5: “Thinking about your years as a woman at Duke, do any particular experiences stand out for you? What do you think you gained from these experiences? What might Duke have done better for you as a young woman?” Answer: “I was lucky to have lived in Epworth for two years where many strong-willed, energetic, creative women students served as role models and challenged me. (I was VP one semester and Pres. another.) They gave me courage. I dropped my math major my sophomore year – was told by my math prof. (a young-ish male – [name redacted]) that women usually don’t make it as mathematicians because they are not aggressive enough. By the end of my soph. year, there was only one other woman besides myself in my math class. I get angry every time I think about the chilling effect this prof. had on my – I sincerely hope that he’s no longer teaching at Duke.”](http://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2019/06/1977_Q5_1.jpg)