The Rubenstein Library’s three research center annually award travel grants to undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and independent scholars through a competitive application process. Congratulations to this year’s recipients, we look forward to working with all of you!

Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture

Jason Ezell, Ph.D. candidate, American Studies, University of Maryland, “Queer Shoulders: The Poetics of Radical Faerie Cultural Formation in Appalachia.”

Margaret Galvan, Ph.D. candidate, English, The Graduate Center, CUNY, “Burgeoning zine aesthetics in the 1980 s through the censored Conference Diary from the controversial Barnard Sex Conference (1982).”

s through the censored Conference Diary from the controversial Barnard Sex Conference (1982).”

Kirsten Leng, assistant professor, Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Breaking Up the Truth with Laughter: A Critical History of Feminism, Comedy, and Humor.

Linda Lumsden, associate professor, School of Journalism, University of Arizona, The Ms. Makeover: The survival, evolution, and cultural significance of the venerable feminist magazine.

Mary-Margaret Mahoney and Danielle Dumaine, Ph.D. candidates, history, University of Connecticut, for a documentary film, Hunting W.I.T.C.H.: Feminist Archives and the Politics of Representation (1968-1979, and present).

Jason McBride, independent scholar, for the first, comprehensive and authorized biography of Kathy Acker.

Kristen Proehl, assistant professor, English, SUNY-Brockport, Queer Friendship in Young Adult Literature, 1850-Present.

Yung-Hsing Wu, associate professor, English, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Closely, Consciously Reading Feminism.

History of Medicine Collections –

Cecilio Cooper, PhD candidate in African American Studies, Northwestern University, for dissertation research on “Phantom Limbs, Fugitive Flesh: Slavery + Colonial Dissection.”

Sara Kern, PhD candidate in History & Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Penn State University, for dissertation work on “Measuring Bodies, Defining Health: Medicine, Statistics, and Civil War Legacy in the Nineteenth-Century America.”

Professor Kim Nielsen, Disability Studies & History, University of Toledo, for research on her book, The Doctress and the Horsewhip, a biography of Dr. Anna B. Ott (1819-1893).

John Hope Franklin Research Center –

Beatrice Adams, Rutgers University – Why African Americans remained in the American South during the Second Great Migration.

Erik McDuffie, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign – Garveyism in the Diasporic Midwest: The American Heartland and Global Black Freedom, 1920 -1980

-1980

Gretchen Henderson, Georgetown University – A narrative and libretto for an opera rooted in African American slavery and history entitled CRAFTING THE BONDS

Maria Montalvo, Rice University – All Could Be Sold: Making and Selling Enslaved People in the Antebellum South (1813-1865)

Nick Witham, University College London, Institute of the Americas – “The Popular Historians: American Historical Writing and the Politics of the Past, 1945-present”

John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising and Marketing History –

FOARE Fellowship for Outdoor Advertising Research:

Dr. Francisco Mesquita, Fernando Pessoa University, Portugal, “Billboard Graphic Production and Design Analysis”

John Furr Fellowship for JWT Research:

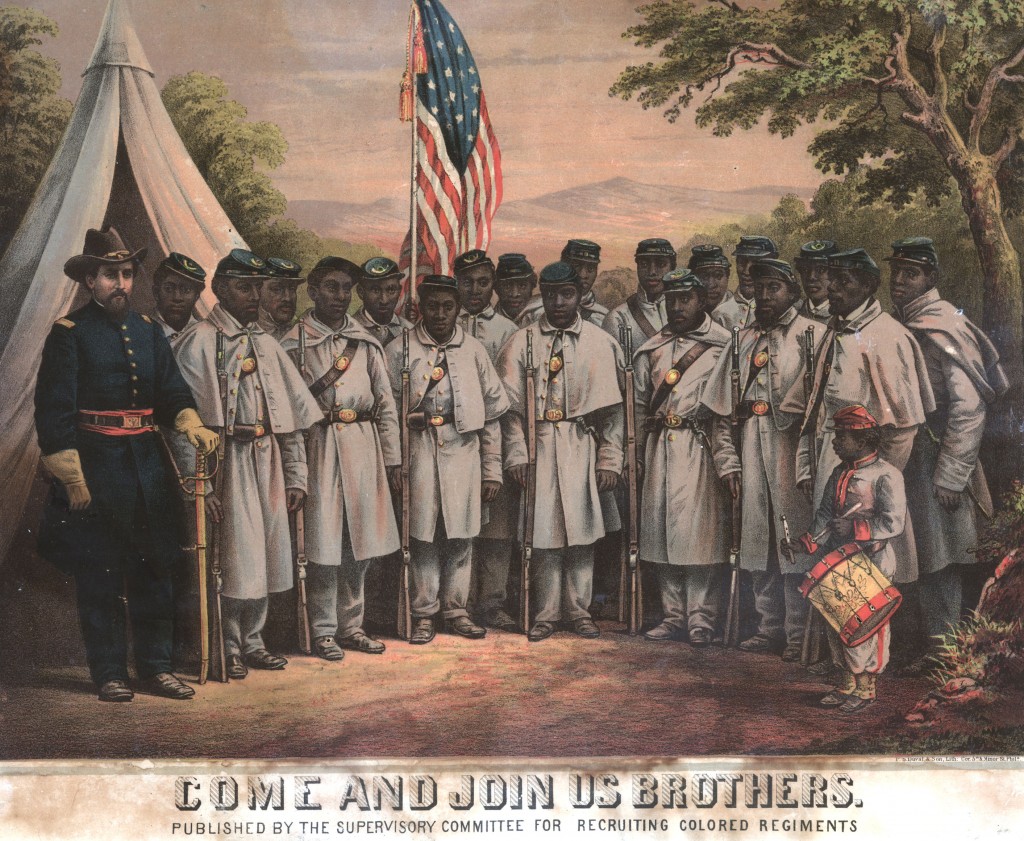

Jeremiah Favara, University of Oregon, “An Army of Some: Recruiting for Difference and Diversity in the U.S. Military”

Alvin Achenbaum Travel Grants:

Faculty:

Megan Elias, Borough of Manhattan Community College, “Be His Guest: Conrad Hilton and the Birth of the Hospitality Industry”

Sarah Elvins, Department of History, University of Manitoba, “Advertising, Processed Foods, and the Changing Notions of Skill in American Home Baking, 1940-1990”

Students:

Alison Feser, Anthropology, University of Chicago, “After Analog: Photochemical Life in Rochester, New York”

Spring Greeney, Environmental History, University of Wisconsin-Madison, “Line Dry: And Environmental History of Doing the Wash, 1841-1992”

Elizabeth Castaldo Lunden, Media Studies – Center for Fashion Studies, Stockholm University, “Oscar’s Red Carpet: Celebrity Endorsements from Local to Global (A Media History)”

Eric Martell, History, State University of New York – Albany, “Kodak Advertising in the U.S. and Latin America, 1920-1960”

Eleanore and Harold Jantz Fellowship:

Dr. Jennifer Welsh, Lindenwood University-Belleville – Research on the presentation of female saints in German Catholic prayers and devotional works from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

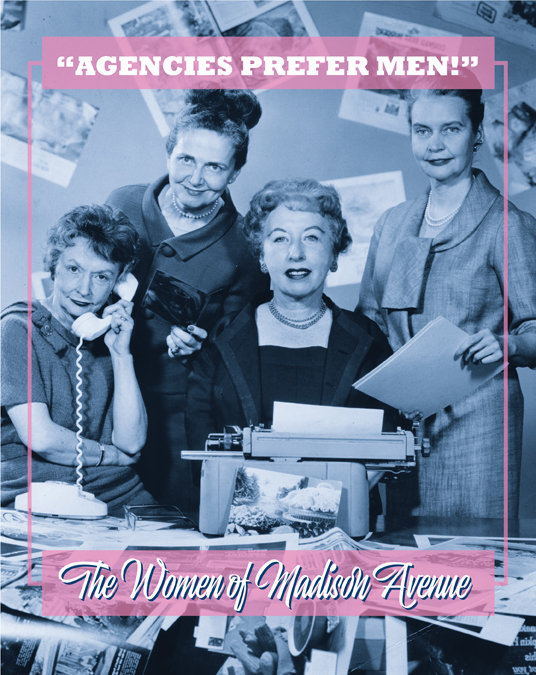

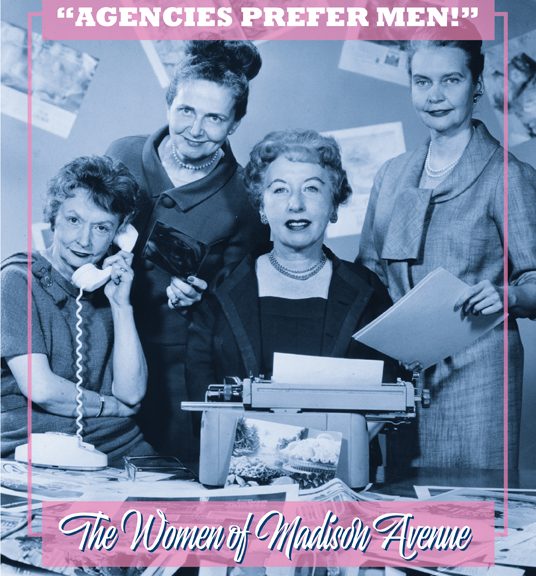

Join the Hartman Center in celebrating its 25th Anniversary with its second event in the anniversary lecture series focusing on Women in Advertising. Helayne Spivak, Director of the Brandcenter at Virginia Commonwealth University, will speak about the status, achievements, and challenges women face in the advertising industry today as well as reflect on her own career and women mentors she has had.

Join the Hartman Center in celebrating its 25th Anniversary with its second event in the anniversary lecture series focusing on Women in Advertising. Helayne Spivak, Director of the Brandcenter at Virginia Commonwealth University, will speak about the status, achievements, and challenges women face in the advertising industry today as well as reflect on her own career and women mentors she has had.

The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is now accepting applications for our 2017-2018 travel grants. If you are a researcher, artist, or activist who would like to use sources from the Rubenstein Library’s research centers for your work, this means you!

The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is now accepting applications for our 2017-2018 travel grants. If you are a researcher, artist, or activist who would like to use sources from the Rubenstein Library’s research centers for your work, this means you!

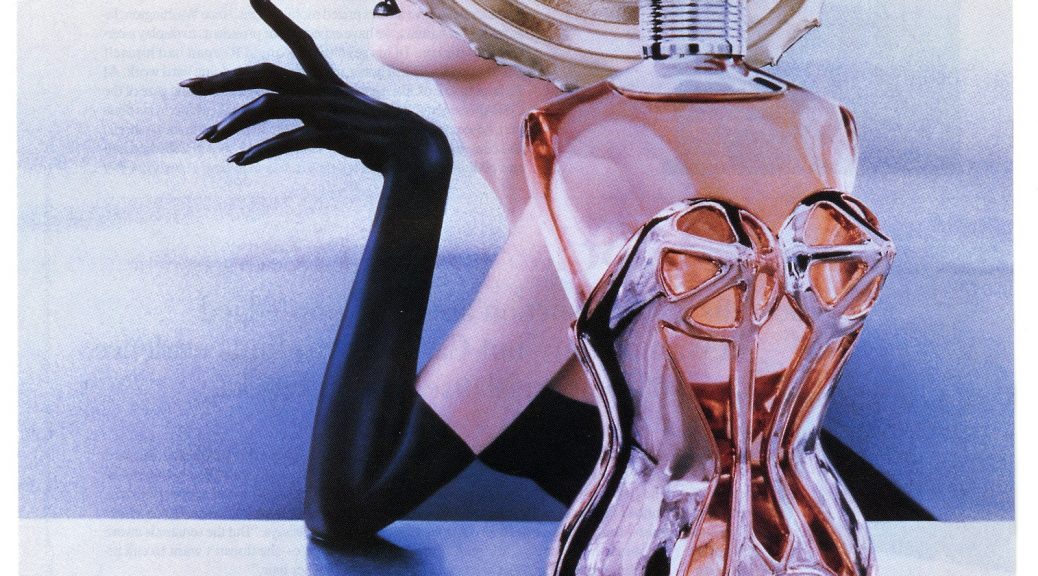

Feminist activist and advertising critic Jean Kilbourne’s pioneering work has helped develop and popularize the study of gender representations in advertising. Her presentation will show if and how the image of women has changed over the past 20 years and powerfully illustrates how these images affect us all. She is the creator of the renowned Killing Us Softly: Advertising’s Image of Women film series and the author of the award-winning book Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel.

Feminist activist and advertising critic Jean Kilbourne’s pioneering work has helped develop and popularize the study of gender representations in advertising. Her presentation will show if and how the image of women has changed over the past 20 years and powerfully illustrates how these images affect us all. She is the creator of the renowned Killing Us Softly: Advertising’s Image of Women film series and the author of the award-winning book Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel.

![cpgsoap004[1]](https://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2016/07/cpgsoap0041-1024x681.jpg)

![cpgsoap002[1]](https://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2016/07/cpgsoap0021-1024x700.jpg)

Two eggs well beaten, one-cup brown sugar, two teaspoons ginger, one-cup N.O. molasses (boiled), one-teaspoon baking soda, flour to roll out. Mix in the order given. I poured the molasses into a pot and watched small bubbles form and subsequently burst as the dark liquid began to heat. As the molasses boiled on the stove, I started mixing the ingredients in the order specified in the recipe. After the eggs had been beaten furiously with my new silver whisk, I began to measure the brown sugar for what I hoped would be a delicious dessert.

Two eggs well beaten, one-cup brown sugar, two teaspoons ginger, one-cup N.O. molasses (boiled), one-teaspoon baking soda, flour to roll out. Mix in the order given. I poured the molasses into a pot and watched small bubbles form and subsequently burst as the dark liquid began to heat. As the molasses boiled on the stove, I started mixing the ingredients in the order specified in the recipe. After the eggs had been beaten furiously with my new silver whisk, I began to measure the brown sugar for what I hoped would be a delicious dessert.