Post written by Spring Greeney, a doctoral candidate in the History Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a recepient of a Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History Alvin A. Achenbaum Travel Grant.

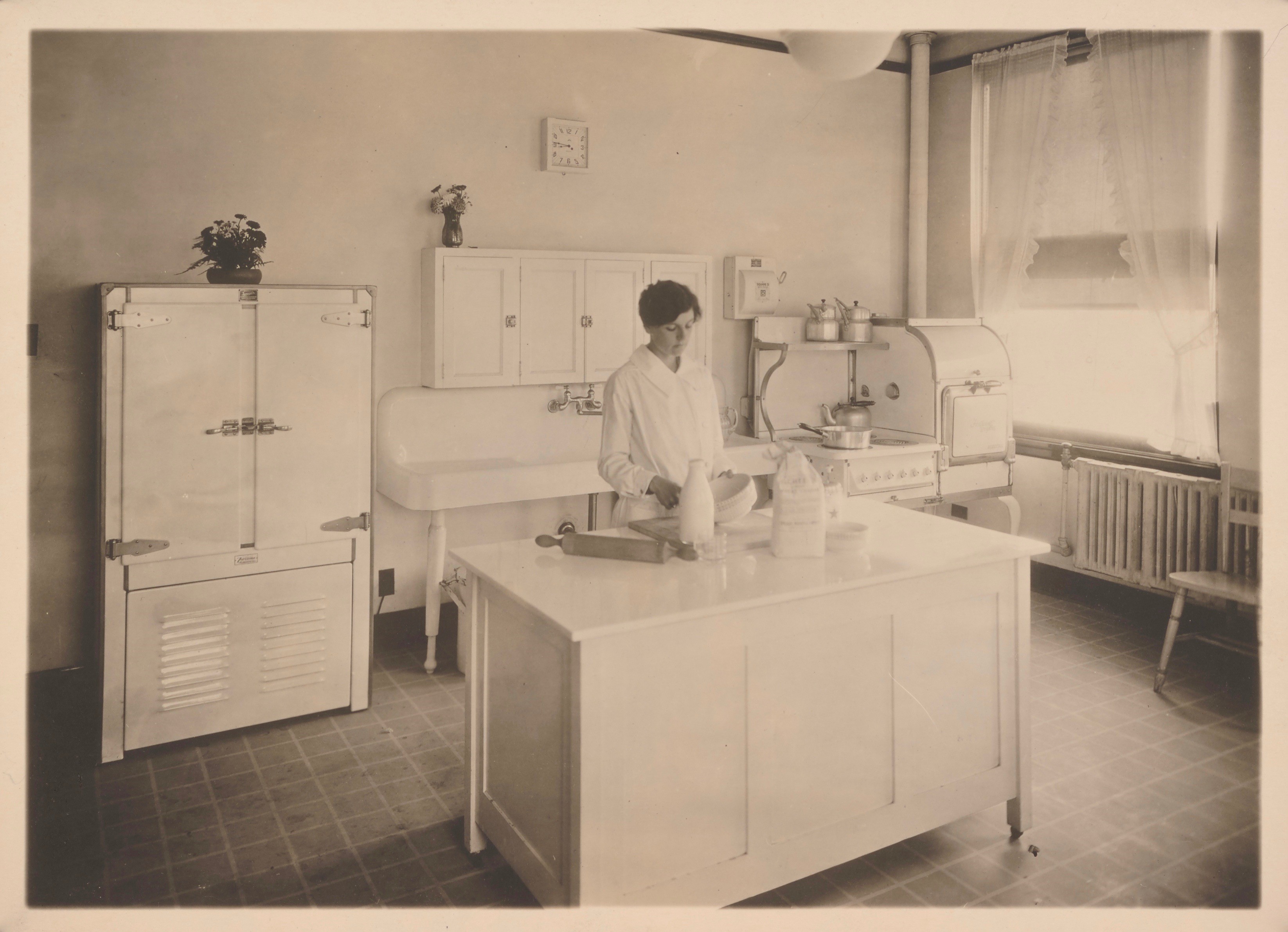

Since at least the late 1930s, advertising firms have been soliciting consumer feedback using what marketing guru Ernest Dichter termed the “focus group:” a laboratory-like controlled environment in which users test a single product while observed or interviewed by product developers. The focus group’s more place-based antecedent, the test kitchen, relies on a similarly anodyne concept of space: gleaming appliances, linoleum flooring, and replicability are the test kitchen’s distinguishing features.

But what more place-attentive research strategies did an advertising giant like J. Walter Thompson Company employ to solicit consumer perspective? To put a finer point on it: prior to the mid-century consolidation of a truly mass market in the U.S., how did a company like JWT account for local heterogeneity—differences in climate, topography, demographics, or consumption habits—when attempting to transform regionally popular products into truly national brands?

In its century-long relationship with JWT, the Lever Brothers soap company serves as an excellent case with which to answer questions about the environmental history of marketing. A British soap manufacturing company begun in 1885, Lever Brothers’ president William Leverhulme had begun as a wholesale butter grocer, a fact that kept the man attentive to the fundamentally ecological roots of his company’s product line. After purchased soap manufacturing plants in Boston and Philadelphia in 1897 and 1899, respectively, Leverhulme set his sights on selling Lever-branded soaps in the expanding U.S. consumer market.

Such sales would not be realized. U.S. sales stagnated following the 1907 roll-out of Lux Soap Flakes and Rinso Laundry Powder in northeastern grocery stores. Consumers remained unmoved by advertising appeals boasting that “This Wonderful New Product Won’t Shrink Woolens!” with the only uptick in sluggish sales confined to March and April. Boxes of Rinso laundry powder, similarly, lingered on drugstore shelves.

Why were American consumers so uninterested? Convinced of the attributes of advertising, the head of the U.S. division of Lever Brothers signed a contract with JWT in 1916 to answer precisely this question.

With focus groups still two decades away, JWT account managers adopted a simple boots-on-the-ground research strategy. In conversations had over fence posts and through screen doors, JWT employees talked with potential customers everywhere from “small towns and Farms in Iowa and South Dakota” to apartment complexes in Chicago, Louisville, New York. 399 interviews in 1918; 328 in 1919; 1741 in 1921.

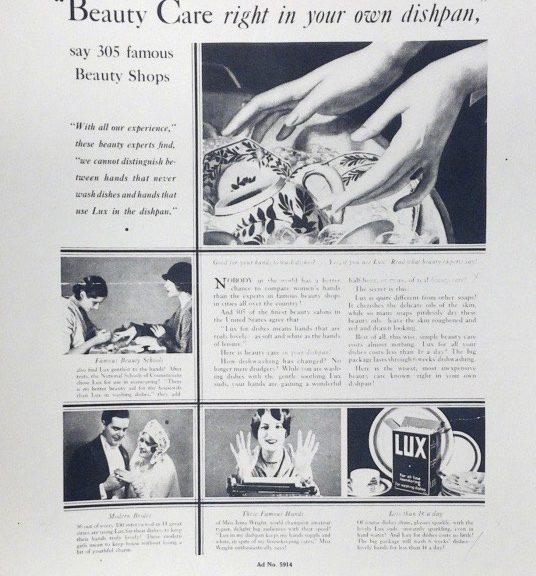

The results were astounding. “Resistances from the customer were mainly … the limitations of the appeal—Lux for washing woolens,” reported one executive, observing that many American buyers of Lux wore silk or synthetics rather than woolen undergarments. “Women liked Lux for easy suds, satisfactory cleansing of dishes and easier on hands,” reported another, with wonder that a product intended for washing flannels was ending up in the kitchen sink. Added another, betraying some defensiveness while bolstering the firm’s claims to effective person-to-person research, “These facts show a continuous contact with the Lux situation.”

Consumers, for their part, were full of ecologically specific requests and recommendations. In New England, buyers explained that they only used Lux during the months of spring cleaning, March and April, to soak winter odors out of woolen blankets and sweaters headed to the attic. The year-round Lux sales pitch (“Won’t shrink woolens!”) had been culturally and seasonally off-key. Or consider this revelation about water chemistry. In regions of the country where hard water was common because of calcium- or magnesium-rich bedrock, Rinso was unpopular because it reacted with dissolved calcium to form a “soap curd” on the top of the wash water. The same problem was cropping up in cities like Boston and New York, where the advent of indoor plumbing had subverted the 19th-century practice of collecting rainwater—always soft—for washing clothes.

Lever Brother products changed in accordance with consumer feedback. As early as 1917, ad copy of Lux began boasting, “Won’t turn silks yellow! Won’t injure even chiffons!” and the box featured reminders that the soap could be used to wash dishes. Lever commercial chemists, meanwhile, increased the fat content of the laundry powder to allow its claim as “the granulated hard-water soap.” The shipping department, meanwhile, acknowledged heterogeneity on the national marketing map: “We are now shipping into the so-called hard water districts Rinso containing 45% fatty acids and the present plans are to bring this percentage up to 48%.” More fatty soap, even if more expensive, would allow uniform product performance across region, regardless of ecological distinction.

Consumer insights such as these, collected via “old-fashioned” direct interviews and telephone calls, remind us that JWT’s early research strategies solicited crucial information for securing Lever Brothers’ financial success in the U.S. JWT’s papers with Lever Brothers also remind us, in echoes, that consumers themselves were active workers and shapers of their local environments. As workers, not just buyers, homemakers were placed in direct contact with messy nature appearing in gritty wash water, uncooperative soaps, delicate fibers, and the weight of wet wool. When and how such consumer identities become politicized, as in the case of the 1970s Lake Erie water pollution contests, is intimately tied to the half-century development of Lever Brothers itself.

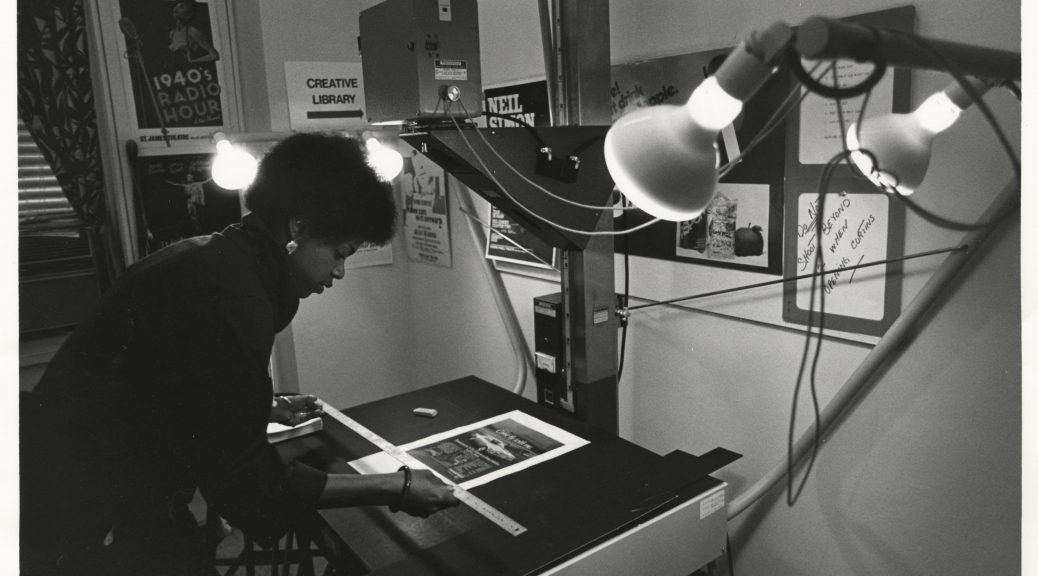

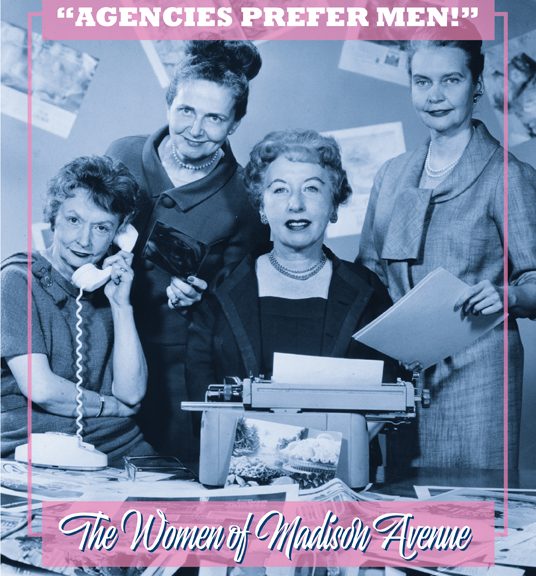

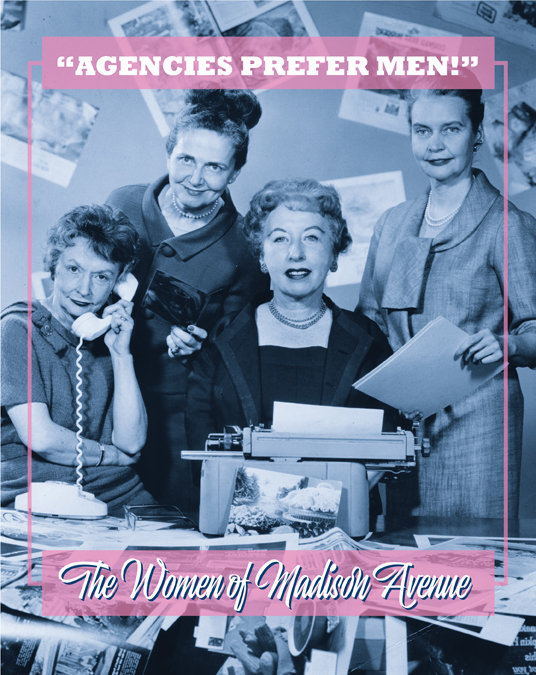

Dr. Judy Foster Davis of Eastern Michigan University’s College of Business will present on her research into the history of African-American women who have worked in the advertising industry. She has recently published a new book on this topic,

Dr. Judy Foster Davis of Eastern Michigan University’s College of Business will present on her research into the history of African-American women who have worked in the advertising industry. She has recently published a new book on this topic,

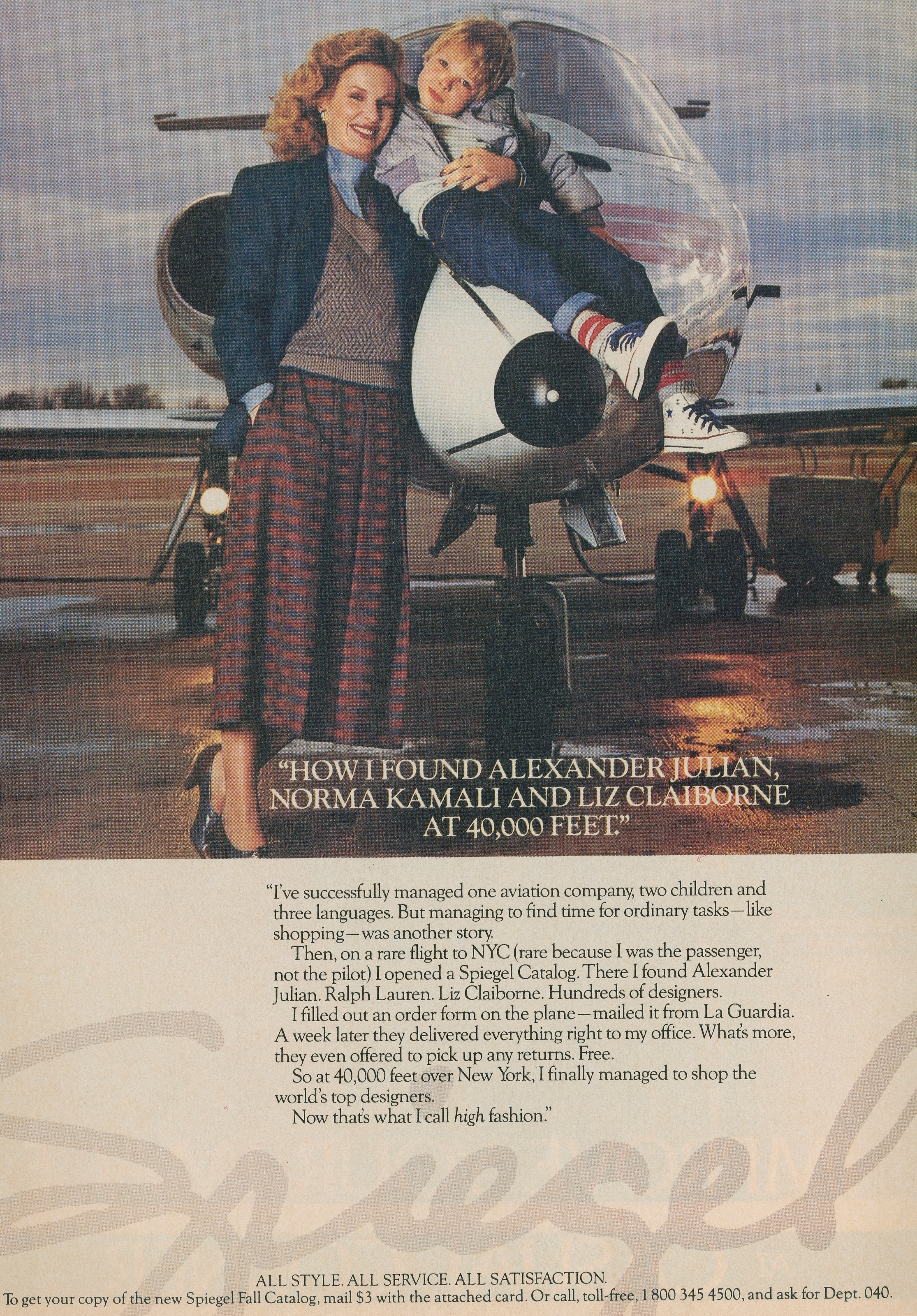

Join the Hartman Center in celebrating its 25th Anniversary with its second event in the anniversary lecture series focusing on Women in Advertising. Helayne Spivak, Director of the Brandcenter at Virginia Commonwealth University, will speak about the status, achievements, and challenges women face in the advertising industry today as well as reflect on her own career and women mentors she has had.

Join the Hartman Center in celebrating its 25th Anniversary with its second event in the anniversary lecture series focusing on Women in Advertising. Helayne Spivak, Director of the Brandcenter at Virginia Commonwealth University, will speak about the status, achievements, and challenges women face in the advertising industry today as well as reflect on her own career and women mentors she has had.

The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is now accepting applications for our 2017-2018 travel grants. If you are a researcher, artist, or activist who would like to use sources from the Rubenstein Library’s research centers for your work, this means you!

The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is now accepting applications for our 2017-2018 travel grants. If you are a researcher, artist, or activist who would like to use sources from the Rubenstein Library’s research centers for your work, this means you!

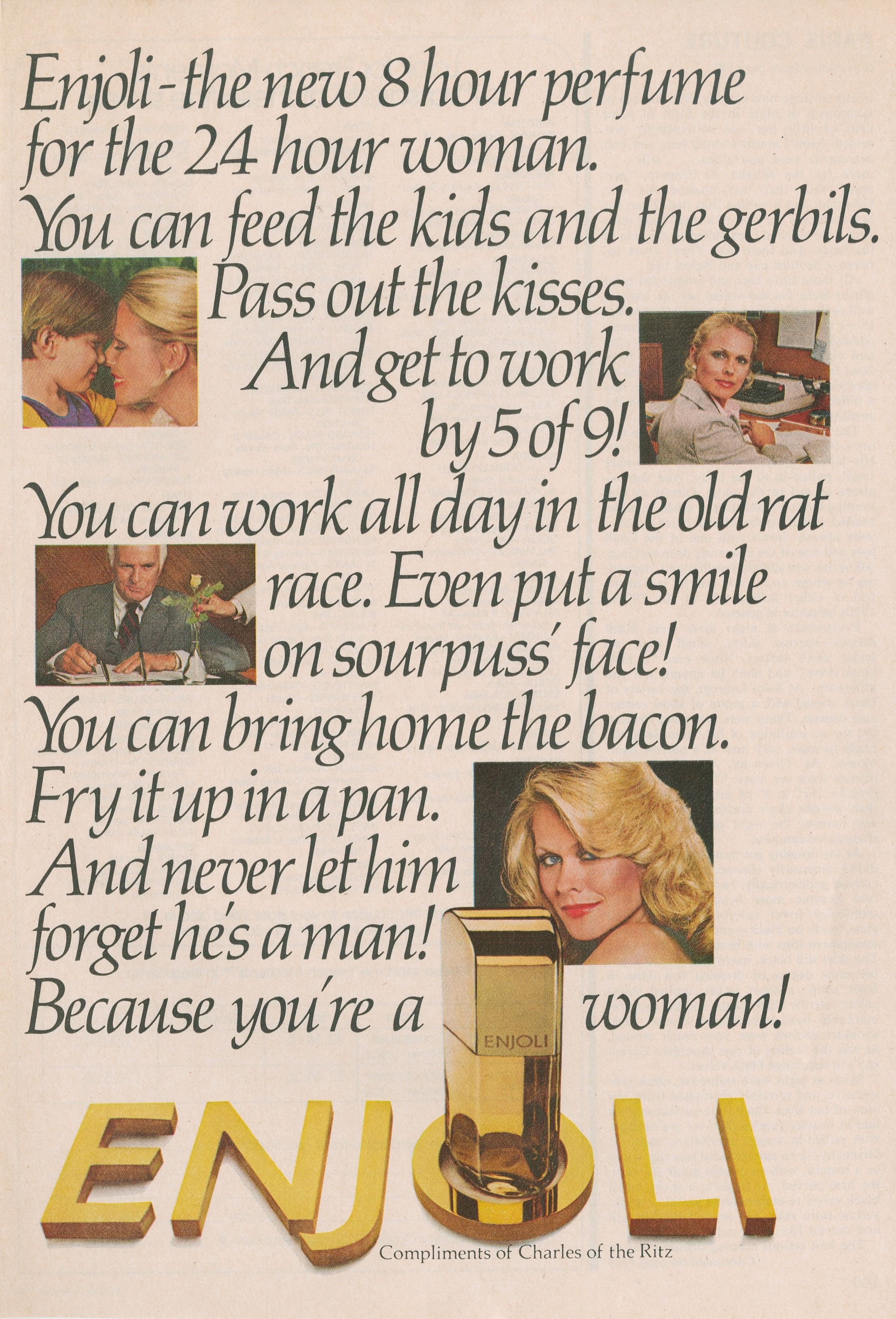

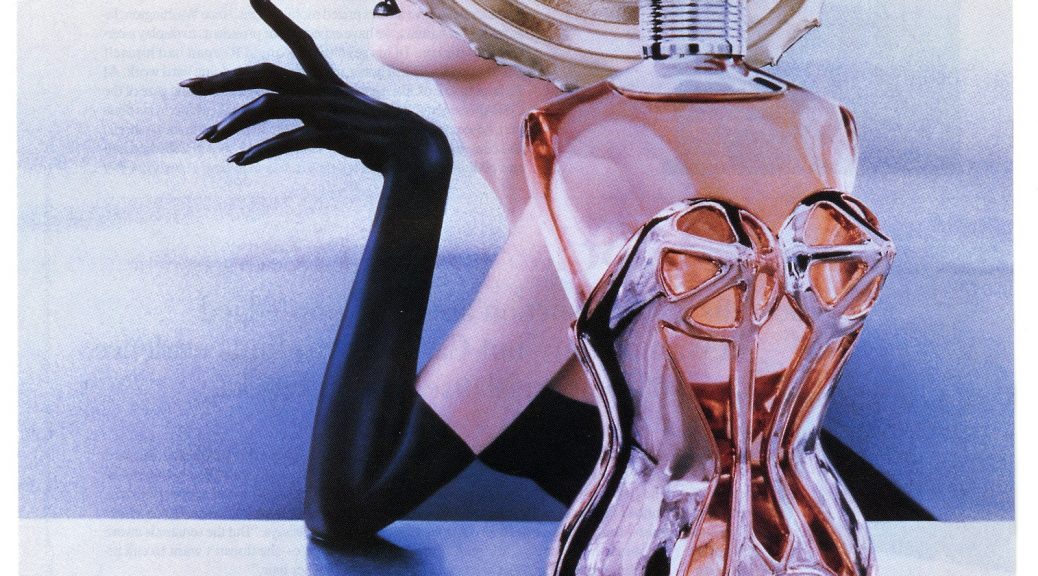

Feminist activist and advertising critic Jean Kilbourne’s pioneering work has helped develop and popularize the study of gender representations in advertising. Her presentation will show if and how the image of women has changed over the past 20 years and powerfully illustrates how these images affect us all. She is the creator of the renowned Killing Us Softly: Advertising’s Image of Women film series and the author of the award-winning book Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel.

Feminist activist and advertising critic Jean Kilbourne’s pioneering work has helped develop and popularize the study of gender representations in advertising. Her presentation will show if and how the image of women has changed over the past 20 years and powerfully illustrates how these images affect us all. She is the creator of the renowned Killing Us Softly: Advertising’s Image of Women film series and the author of the award-winning book Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel.