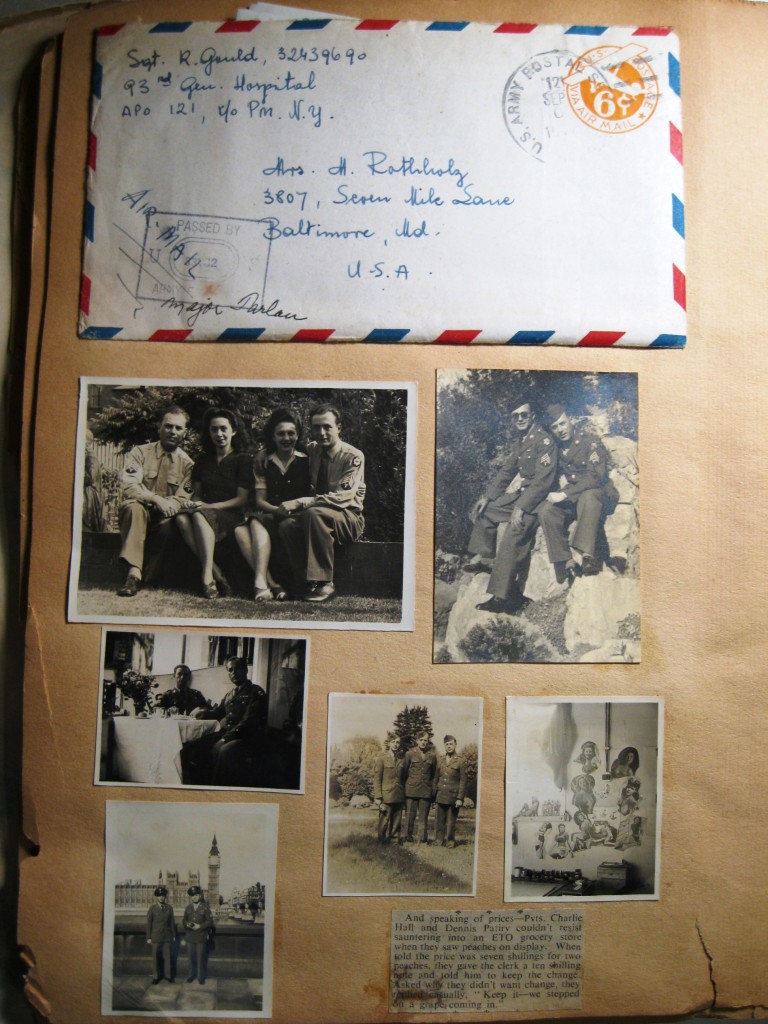

The Library recently acquired a small album of photographs taken in Virginia’s Tidewater region. It contains six cyanotypes depicting work at the freight docks of Newport News and other subjects. Of particular interest is a laid-in cyanotype which appears to be a portrait of Frances Benjamin Johnston, a pioneering female American photographer.

The Library recently acquired a small album of photographs taken in Virginia’s Tidewater region. It contains six cyanotypes depicting work at the freight docks of Newport News and other subjects. Of particular interest is a laid-in cyanotype which appears to be a portrait of Frances Benjamin Johnston, a pioneering female American photographer.

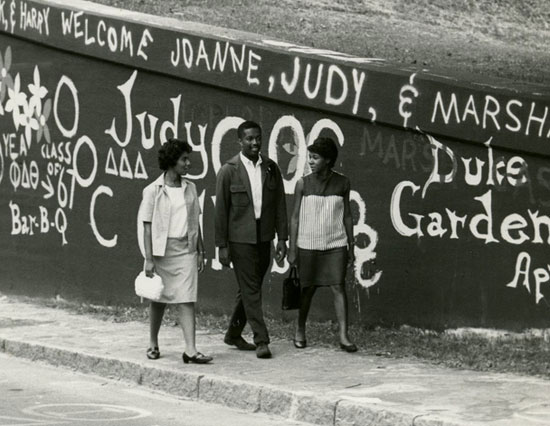

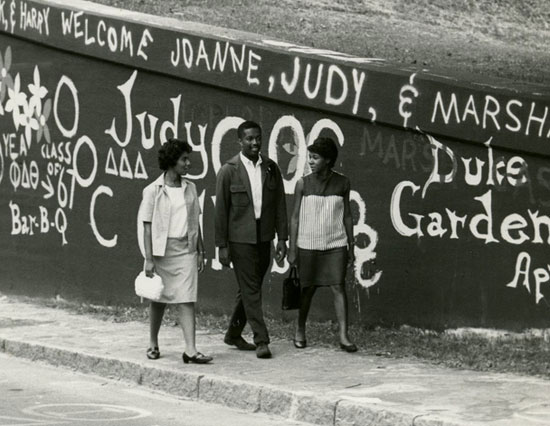

Johnston was a remarkable photographer. She took portraits of American presidents and the high society of the turn of the nineteenth century from her Washington, D.C. studio, but also participated in ambitious documentary projects, such as her architectural photographs of Southern states. For one of her best-known commissions, she traveled to Virginia to document the students of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in 1899-1900. Her photographs of this important education institution for African Americans and Native Americans are preserved in her collection at the Library of Congress.

Based on the probable identification of the woman in the photograph as Johnston and the photographs of the area around Hampton in the album, these photographs have been dated to the first decade of the 1900s. However, no information about the photographer is yet known. Were they a student or colleague of Johnston? Is it possible that the photographs (or some of the photographs) are by Johnston herself?

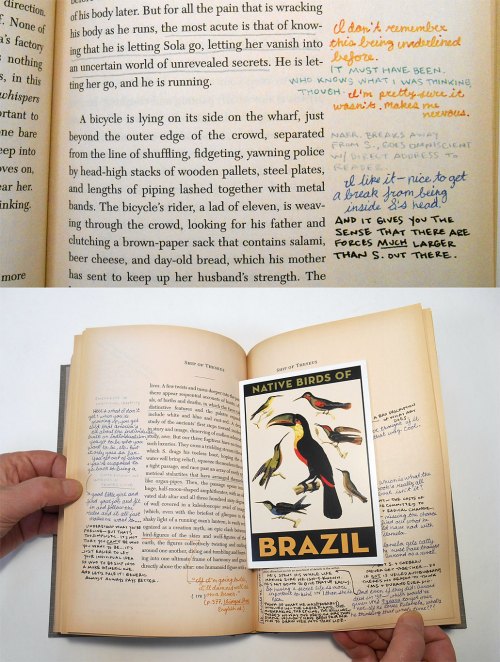

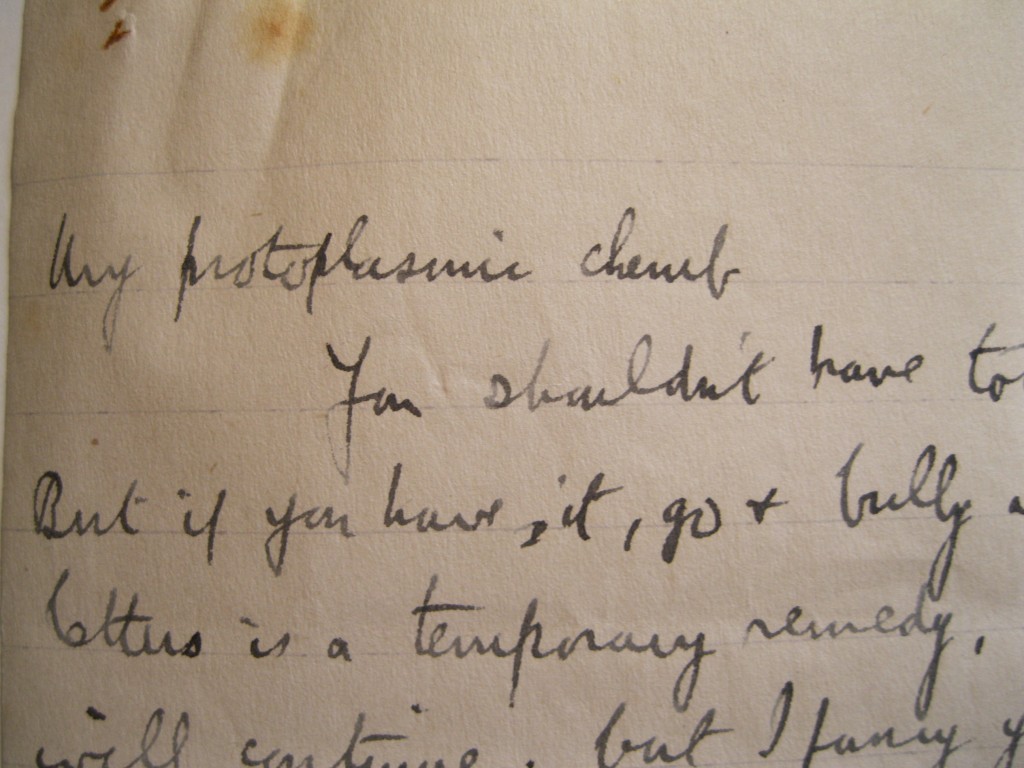

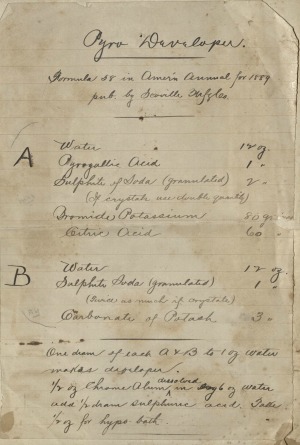

The album is also accompanied by handwritten directions for making “Pyro Developer” and a “fixing bath for platinum prints,” which may provide further evidence that the creator may have been a student or novice photographer. (The large initial “B” on the “Pyro Developer” formula bears some resemblance to Johnston’s handwriting, but the handwriting of the rest of the formula does not appear to be similar to hers.)

The album is also accompanied by handwritten directions for making “Pyro Developer” and a “fixing bath for platinum prints,” which may provide further evidence that the creator may have been a student or novice photographer. (The large initial “B” on the “Pyro Developer” formula bears some resemblance to Johnston’s handwriting, but the handwriting of the rest of the formula does not appear to be similar to hers.)

If anyone has clues or guesses to contribute to the mystery of the photographer’s identity, please share them in the comments section below!

Post contributed by Will Hansen, Assistant Curator of Collections.