One of my favorite Rubenstein collections is the C.C. Clay Papers, which document the life and times of Clement Claiborne Clay and his family. The Clays lived in Alabama in the nineteenth century, and sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War. In the war’s early years, C.C. Clay served as a Confederate States senator. His opposition to raising soldiers’ pay (it would have been too expensive!) led to his being voted out of office in 1863. Clay and Confederate States President Jefferson Davis were good friends, however — Clay was godfather to Davis’s son Joseph — and rather than send Clay back to his plantation, Davis sent him on a secret mission to Canada to spy, bribe, and generally foment rebellion. (Clay’s mission did not end up helping the C.S.A.)

Clay was in Canada from mid-1864 through early 1865. He returned to the South just in time for the Confederacy to surrender. President Lincoln was assassinated shortly after his return, and both Davis and Clay were arrested by the Federal government on suspicions of treason relating to Lincoln’s assassination. (Clay’s time in Canada looked extremely suspicious.) The men were imprisoned in Fortress Monroe, Virginia. Clay was held for about a year without being charged until finally his wife, Virginia Clay, convinced President Andrew Johnson to pardon him. (She was a cool lady. You can read her 1905 memoir here.) Davis was imprisoned until 1867 before finally being released on bail.

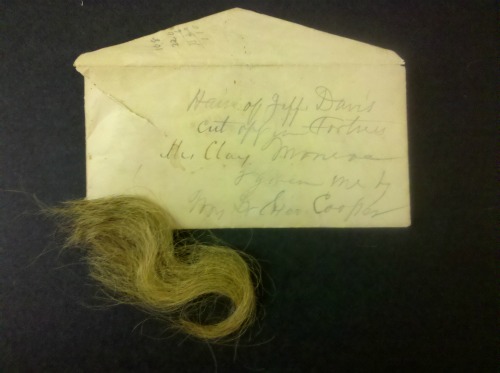

What does all this backstory have to do with Jefferson Davis’s hair? Well, there are giant clumps of it in the Clay Papers, and for years we did not know why. The mystery behind the hair did not stop us from displaying it in a Perkins Library exhibit three years ago. The only clue was from an envelope, where Virginia Clay had written, “Hair of Jefferson Davis cut off in Fortress Monroe, given me by Mrs. Dr. Elva Cooper.”

Recently, in reading through the Clay Papers correspondence, I came across the letter that explains it all. Virginia Clay wrote to Elva Cooper in April 1866, days before receiving Johnson’s pardon for C.C. Clay, asking her to “do send the hair if possible as directed.” Later on in the letter, Virginia recounted the number of donations received toward Jefferson Davis’s bail, adding that “the hair will sell like wildfire + will be my contribution.”

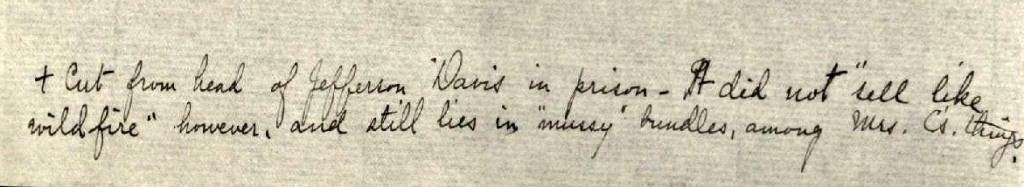

It appears that the plan was for the clumps of hair to be sold to Davis supporters as souvenirs, raising money for his aid. This explanation makes a lot more sense than the various reasons we had thought up over the years. Hair tokens are not rare in manuscript collections, but the fact that the Clays had so much of it struck us as a little odd. Fortunately, the story doesn’t end there. An annotation from Ada Sterling, the editor for Virginia’s memoir, offers this extra gem:

It appears that the plan was for the clumps of hair to be sold to Davis supporters as souvenirs, raising money for his aid. This explanation makes a lot more sense than the various reasons we had thought up over the years. Hair tokens are not rare in manuscript collections, but the fact that the Clays had so much of it struck us as a little odd. Fortunately, the story doesn’t end there. An annotation from Ada Sterling, the editor for Virginia’s memoir, offers this extra gem:

Even Davis’s contemporaries were not interested in purchasing locks of his hair! Sterling explained that as she helped write the memoir in the early 1900s, the hair was still lying in “‘mussy’ bundles, among Mrs. C’s things.”And so it now remains forever in the Rubenstein. Mystery solved!

Even Davis’s contemporaries were not interested in purchasing locks of his hair! Sterling explained that as she helped write the memoir in the early 1900s, the hair was still lying in “‘mussy’ bundles, among Mrs. C’s things.”And so it now remains forever in the Rubenstein. Mystery solved!

Post contributed by Meghan Lyon, Technical Services Archivist.