Post contributed by Lucy Dong, T’20, Middlesworth Social Media and Outreach Fellow (2019-2020)

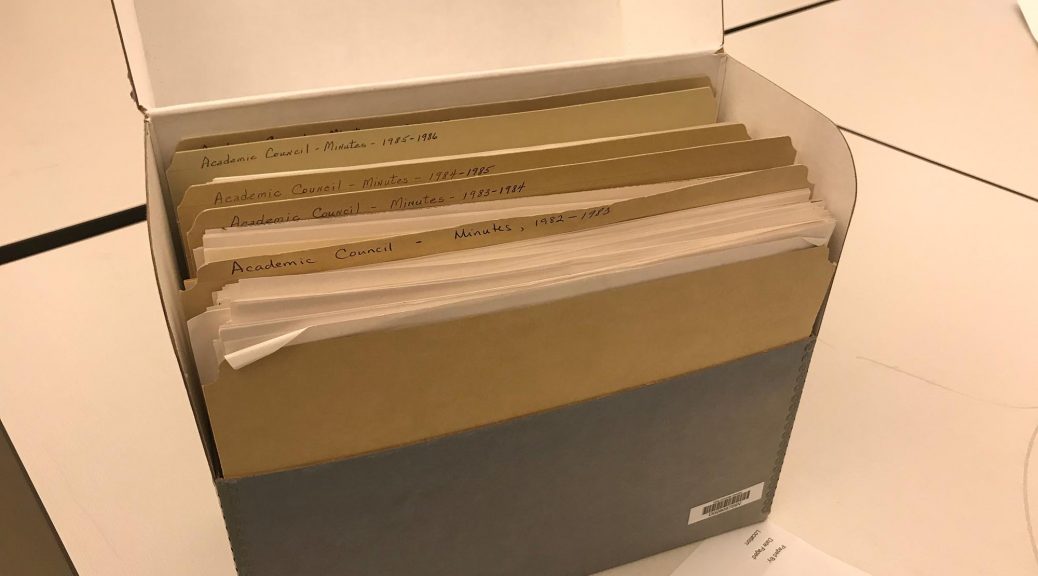

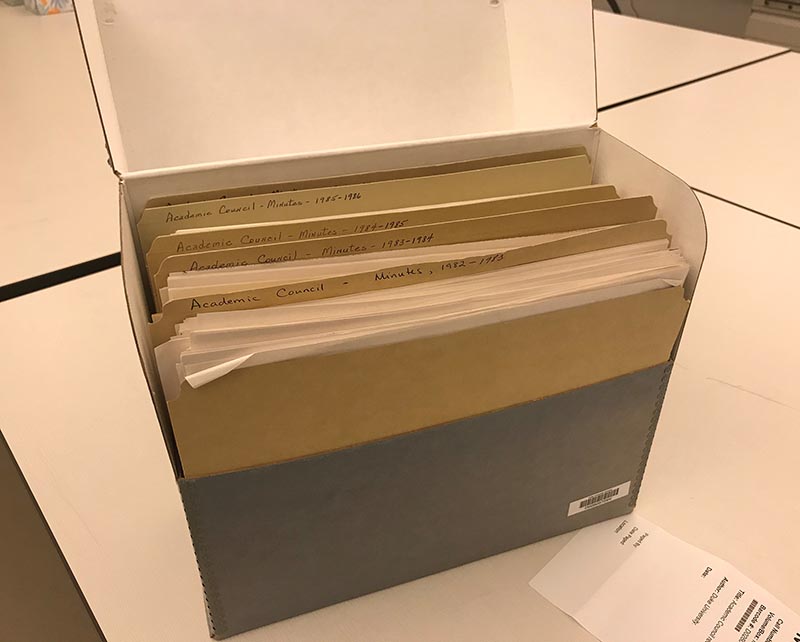

Back in February, I was busy combing the archives for cool stories and important figures in black history to share on our social media (follow us on Instagram!) That’s when Dr. Trudi Abel, Research Services Archivist, tipped me off to an interesting find in the Charles N. Hunter Papers, 1850s-1932 , a black educator, journalist, and reformer from Raleigh, North Carolina. The Hunter papers are all digitized, so you can check them out even while the Rubenstein is closed.

Dr. Abel has taught a course called Digital Durham for many years, and she’s found that the Charles N. Hunter Papers are especially underutilized for what it reveals about education of black students in Durham. For example, in some of his correspondence, we get insight into the beginning days of what was called the Durham Colored Graded School. Later named the Whitted School after their principal Rev. James A. Whitted (Durham’s first black principal), the Durham Colored Graded School was created in response to the earlier Durham Graded School which gave only white students access to the modern graded model of teaching by age group.

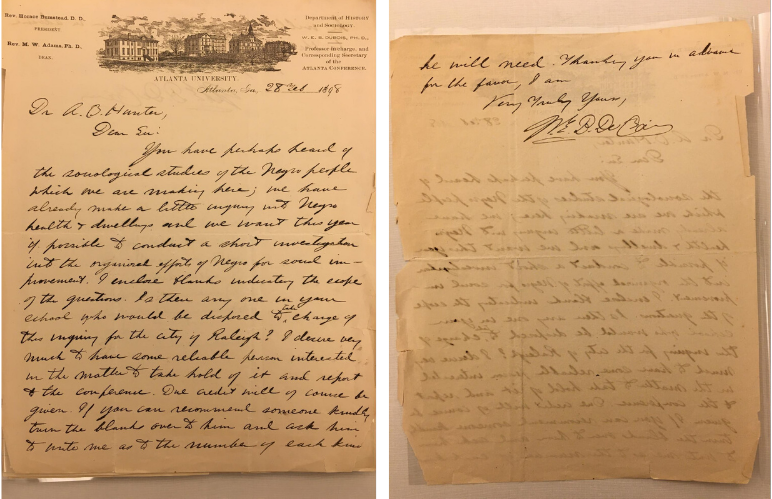

Among letters to other educators, the nation’s first black congressmen, and more personal family matters, there’s a letter from prominent black scholar W. E. B Du Bois. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington happened to visit Durham in the same year, both commenting on the rich culture and entrepreneurial spirit of its black community during Reconstruction. One primary symbol of that prosperity was North Carolina Mutual Insurance, created by black entrepreneurs to serve their community, which established (white) insurance companies refused to service. NC Mutual paved the way for a flourishing, though segregated, black business district.

Washington saw Durham as a great example of black people helping themselves out of poverty and saw segregation as a reasonable means to achieve “racial self-help and uplift.” Du Bois celebrated the success of Durham’s black community, but generally pushed harder to demand full civil rights. In this letter, Du Bois is seeking recommendations for someone to help him do some sociological studies on social improvement in black communities, especially pertaining to the South.

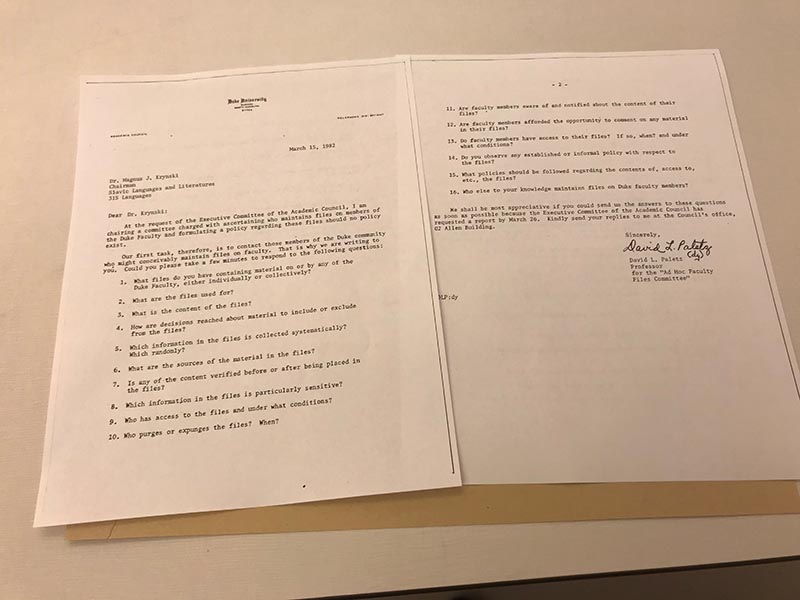

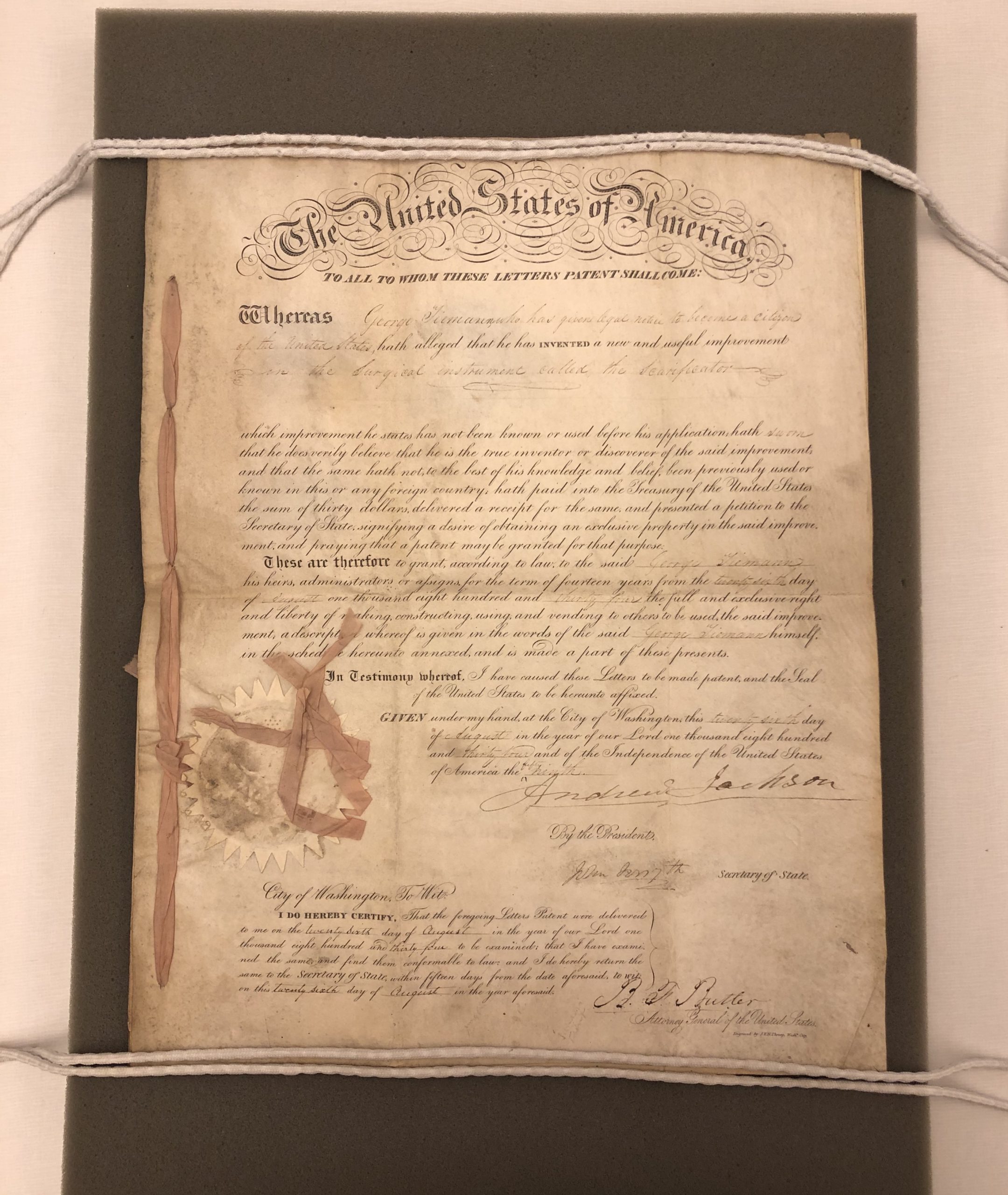

Can you make out all the words here? Dr. Abel regularly has her students do transcription projects to become familiar with reading older documents. The handwriting is not the easiest thing to read, but thanks to contextual clues and some corrections by Dr. Abel, I came up with the following:

Dr. A.B. Hunter, Dear Sir:

You have perhaps heard of the sociological studies of the Negro people which we are making here; we have already made a little inquiry with Negro health and dwellings and we want this year if possible to conduct a short investigation into the organizational efforts of Negro [sic] for social improvement. I enclose blanks [survey forms] indicating the scope of the questions. Is there anyone in your school who would be disposed to take charge of the inquiry for the city of Raleigh? I desire very much to have some reliable person interested in the matter to take hold of it and report to the conference. Due credit will of course be given. If you recommend someone kindly turn the blanks over to him and ask him to write me as to the number of each kind he will need. Thanking you in advance for the favor, I am

Very Truly Yours,

W. E. B DuBois

But wait, I thought these were the records of Charles N. Hunter, not A. B. Hunter. Were they related? Why was this piece of correspondence included in Charles N. Hunter’s personal records? A separate letter provides our missing link:

My dear Mr. Hunter,

I enclose Prof. DuBois’ letter and have written him that you were hopefully most familiar with the societies he indicated in his letter. I hope you will be able to undertake the work. I regard his investigation as of very great importance. Will you kindly write him.

Very truly yours,

A.B. Hunter

Rev A. B. Hunter, Dean of St. Augustine’s School – now St. Augustine’s University, a historically black college in Raleigh – recommended Charles N. Hunter to help with Du Bois’ study. Quick searches into ancestry records and census documents did not indicate a familial connection.

Thanks to Dr. Abel for this fun experience piecing together the context and the connections between these three black educators. It was exciting to first interpret the handwritten letter, then search for the reason it was included in this collection and learn a little more about Durham’s past. Such are the small thrills of doing work in the archives–turning over fragile pieces of history to uncover things I didn’t know I didn’t know.

The Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2020-2021 travel grants. Our research centers annually award travel grants to students, scholars, and independent researches through a competitive application process. We extend a warm congratulations to this year’s awardees. We look forward to meeting and working with you!

The Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2020-2021 travel grants. Our research centers annually award travel grants to students, scholars, and independent researches through a competitive application process. We extend a warm congratulations to this year’s awardees. We look forward to meeting and working with you!