Post contributed by [Matthew] Farrell, Digital Records Archivist.

I last wrote about harvesting Twitter for the archives way back in April 2016. Toward the end of that post I expressed our ambivalence toward access, essentially being caught between what Twitter allows us to do, what is technologically possible, and (most importantly) our ethical obligations to the creators of the content. Projects like Documenting the Now were just starting their work to develop community ethical and technological best practices in social media harvesting. For these reasons, we halted work on the collecting we had done for the University Archives, monitoring the technological and community landscape for further development.

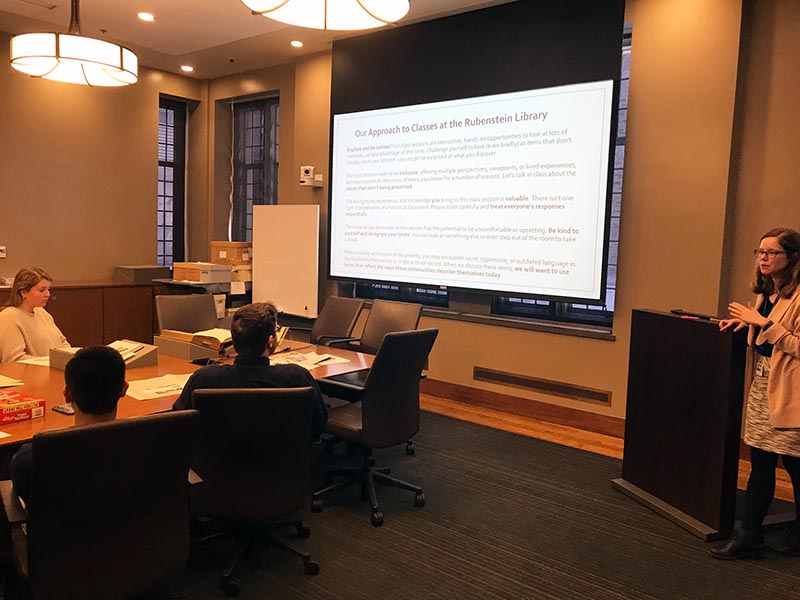

February 2019 saw the 50th Anniversary of the Allen Building Takeover, when a number of Duke students occupied the Allen Building to bring attention to the needs of African-American students and workers on campus (here is a much better primer on the takeover). There were a number of events on campus to commemorate the takeover on campus, both in the Rubenstein Library and elsewhere. As is de rigueur for academic events these days, organizers decided on an official hashtag, which users could use to tweet comments and reactions. Like we did in 2016, we harvested the tweets associated with the hashtag. Unlike 2016, community practice has evolved enough to point to a path forward to contextualizing and providing access to the harvested tweets. We also took the time to update the collection we harvested in 2016 in order to have the Twitter data consistent.

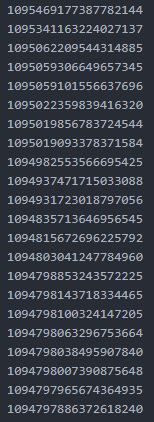

In terms of technology, we use twarc a tool and Python library created by DocNow, to harvest and process Twitter content. Twarc interacts with the Twitter API and produces output files in JSON format. The image here is an example of JSON, which is clearly not human readable, but is perfect for machine processing as a data set.

But twarc also allows the user to work with the JSON in different ways. Some of these are obviously useful–e.g., you can create a basic HTML version of the data set.

Those funky characters are because twarc has a hard time encoding emoji. These web comics (here and here) are not full explanations, but point to some of the issues present. If you take nothing else from this, observe that you can somewhat effectively obscure the archival record if you communicate solely in emoji.

Finally, for our ability to offer access in a way that both satisfies Twitter’s Terms of Service and Developer Agreement, twarc allows us deyhdrate a data set and respect the wishes of the creator of a given tweet. “Dehydration” refers to creating a copy of the data set that removes all of the content except for Twitter’s unique identifier for a tweet. This results in a list of Tweet IDs that an end user may rehydrate into a complete data set later. Importantly, any attempt to rehydrate the data set (using twarc or another tool), queries Twitter and only returns results of tweets that are still public. If a user tweeted something and subsequently deleted it, or made their account private, that tweet would be removed from rehydrated data set even if the tweet was originally collected.

What does this all mean for our collections in the University Archives? First, we can make a dehydrated set of Twitter data available online. Second, we can make a hydrated set of Twitter data available in our reading room, with the caveat that we will filter out deleted or private content from the set before a patron accesses it. Offering access in this way is something of a compromise: we are unable to gain proactive consent from every Twitter user whose tweets may end up in our collections nor is it possible to fully anonymize a data set. Instead we remove material that was subsequently deleted or made private, thereby only offering access to what is currently publicly available. That ability, coupled with our narrow scope (we’re harvesting content on selected topics related to the Duke community in observance of Twitter’s API guidelines), allows us to collect materials relevant to Duke while observing community best practices.

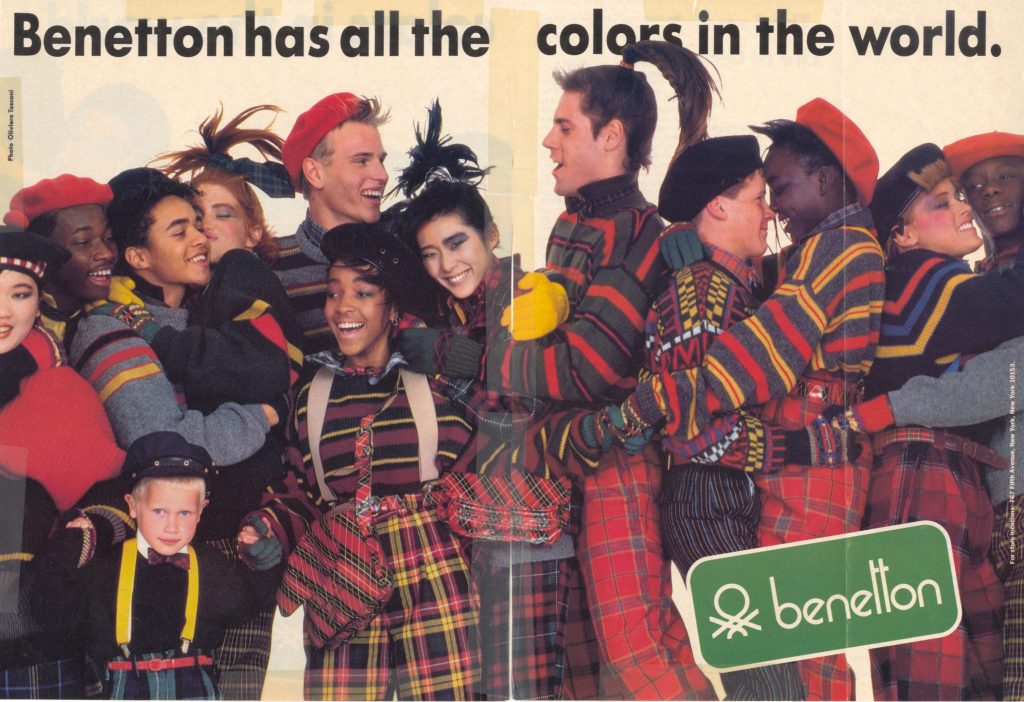

While still invoking the theme of inclusivity, the ad signaled a change in Benetton’s marketing aesthetic. In the 1990s, Benetton ads seemed to be more focused on shock value than clothing. Many of their most controversial images featured no Benetton clothing. Instead, they depicted a wide range of social and political phenomena, from soldiers in the Bosnian war, to a baby with its umbilical cord attached, to a nun and a priest kissing, to a dying AIDS activist. These advertisements were often met with backlash, calls for a boycott of Benetton goods, and, at times, with censorship. Toscani justified these ads in an

While still invoking the theme of inclusivity, the ad signaled a change in Benetton’s marketing aesthetic. In the 1990s, Benetton ads seemed to be more focused on shock value than clothing. Many of their most controversial images featured no Benetton clothing. Instead, they depicted a wide range of social and political phenomena, from soldiers in the Bosnian war, to a baby with its umbilical cord attached, to a nun and a priest kissing, to a dying AIDS activist. These advertisements were often met with backlash, calls for a boycott of Benetton goods, and, at times, with censorship. Toscani justified these ads in an