Post contributed by Bennett Carpenter, PhD Candidate in Literature and African and African American Studies Intern

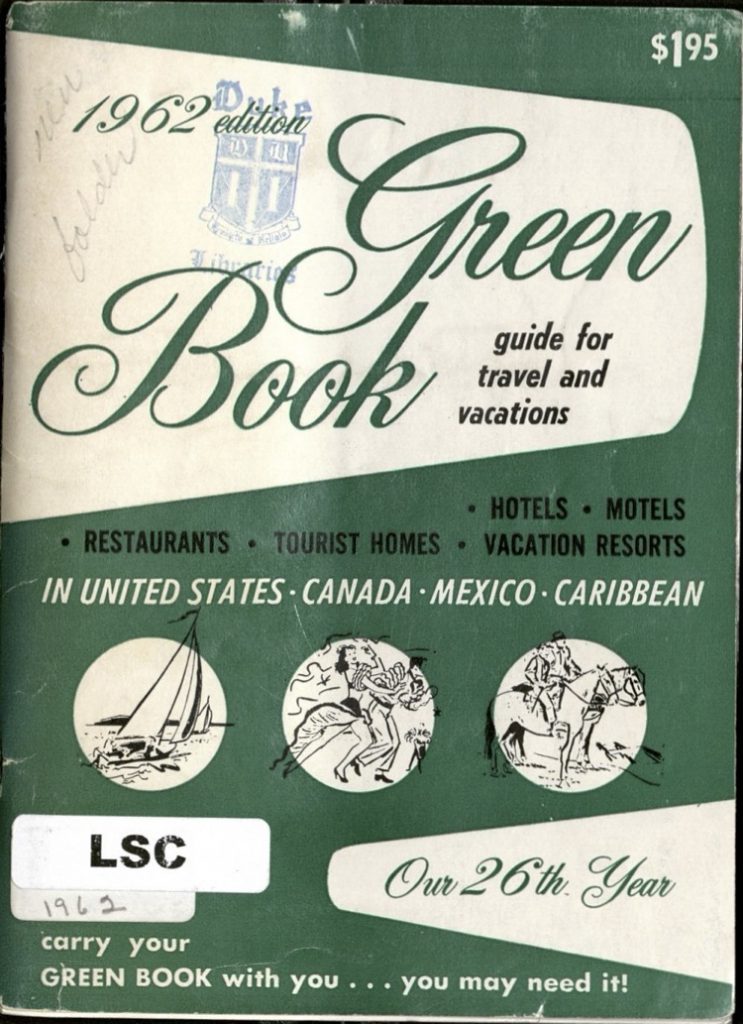

The movie Green Book, in theaters now, has garnered both acclaim and criticism for its depiction of the African American pianist Don Shirley’s 1962 tour through the Jim Crow South. But it has also engendered newfound interest in the original Green Book, a vital resource for African American travelers in the early- to mid-twentieth century.

Car travel appealed to many African Americans in the Jim Crow era, both for the sense of freedom it engendered and as a means to escape the segregation and discrimination experienced in public transportation. But travelling by car presented its own difficulties. In addition to the pervasive threat of police harassment on the road, many hotels, restaurants and even gas stations refused to cater to Black customers—not only in the overtly segregated South but also in the nominally integrated North. As a result, Black travelers had to plan ahead.

First published in 1936, the Negro Motorist Green Book provided African Americans with an invaluable guide to relatively safe stopping points along the road, along with a list of local businesses that would provide food, gas, a place to sleep and a warm welcome. The book was created and published by New York City mailman Victor Green, who tapped into a network of Black postal workers across the country to provide him with information about local conditions.

Here at the John Hope Franklin Research Center, we hold a copy of the Green Book from the same year that the film takes place—1962. A glance through its pages grants many insights into African American life in the mid-20th century. The entry for Durham, North Carolina, for instance, lists two restaurants, a hostelry and a hotel—all located in the historic Black neighborhood of Hayti.

Founded by freedmen in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Hayti was an important center of Black life for the better part of a century. It attracted such famous visitors as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, who called it “the Negro business mecca of the South,” recommending it as a model for other African American communities to follow.

By the time the 1962 Green Book appeared, however, the community was on the verge of precipitous decline. That same year, the city voted to build Highway 147 through the middle of the neighborhood, dividing the community and destroying hundreds of homes and businesses. Federal money promised for rebuilding failed to materialize. The community would be further torn apart by additional attempts at so-called “urban renewal”—famously dubbed “Negro removal” by James Baldwin for its disastrous impact on Black communities.

Today, none of the four Durham businesses listed in the 1962 Green Book remain. Two—the Bull City Restaurant and the Biltmore Hotel, both on Pettigrew Street—have been torn down, the once bustling businesses replaced by parking lots. DeShazor’s Hostelry has also been demolished; a strip mall now occupies the spot where it once stood. At 1306 Fayetteville Street, the former College Inn Restaurant has been replaced by the New Visions of Africa Community Restaurant. Opened in 2004, it provides free daily snacks to children and sells low-cost, healthy meals, with an emphasis on community self-sufficiency.

The Green Book was not the only such travel guide available to African American motorists. A 1956 booklet in our holdings, simply titled Travelguide, also promised to help Black travelers experience “Vacation & Recreation Without Humiliation,” as a caption on the cover put it. Inside the booklet, an inset note predicted that “the time is rapidly approaching when TRAVELGUIDE will cease to be a ‘specialized’ publication,” envisioning “the day when all established directories will serve EVERYONE.”

That day was not far off. In 1964, the passage of the Civil Rights Act ended legal racial discrimination in hotels, restaurants and all other public accommodations, muting the need for specialized travel guides. Within a few years, publication of the Green Book and other Black travel guidebooks would cease. The Travelguide’s optimistic proclamation had thus proved prophetic.

On the top of the same page from the 1956 Travelguide, however, another inset sounded a different note. “Many of the N.A.A.C.P. Presidents in southern states have been removed from this issue,” it announced, “due to the danger of increased violence by those individuals who are opposing the Supreme Court and the Interstate Commerce Commission in respect to segregation in travel.”

In the gap between these two insets—the one prophesizing an end to racial discrimination, the other warning of increasing racist violence—can be read both the triumphs and tribulations of the Black freedom struggle across the twentieth century.