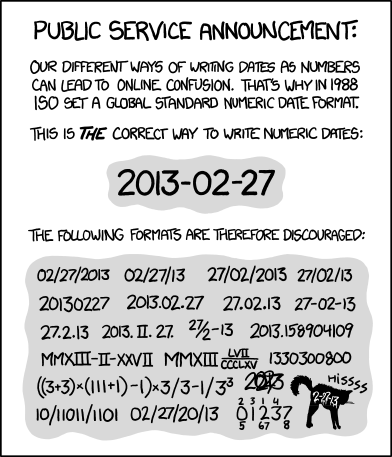

You might think that three posts about the Extended Date Time Format (EDTF) is three too many for one blog, but we who work with digital collections are very enthusiastic about dates. In two previous posts (Enjoy your Metadata: Fun with Date Encoding and It’s Date Night Here at Digital Projects and Production Services), Maggie and I (separately) wrote about our date metadata for digital collections and our reasons for migrating to EDTF.

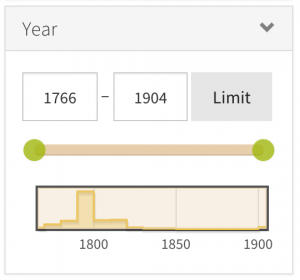

To recap, EDTF is a machine readable date encoding standard that enables us to record dates with various levels of precision and certainty — important for cultural heritage collections.

One challenge of working with EDTF formatted dates is that it’s not necessarily obvious to humans what they mean. To the best of my knowledge, the available tools for working with EDTF dates are intended for parsing EDTF strings into objects that are understandable to programming languages. This is great for working with EDTF dates if you want to have the software do things like sort a list of items into date order or provide a searchable index of years. These tools are less helpful for outputting human readable versions of EDTF encoded dates, such as for an item’s metadata record display.

For instance, many of the photographs in the Alex Harris collection are dated with a season and year, such as “summer 1972.” EDTF specifies that “summer 1972” should be encoded as “1972-22.” This is great for our digital collections software, which knows what “1972-22” means (thanks to the EDTF gem). However, people unfamiliar with the EDTF standard will likely not understand what the date means.

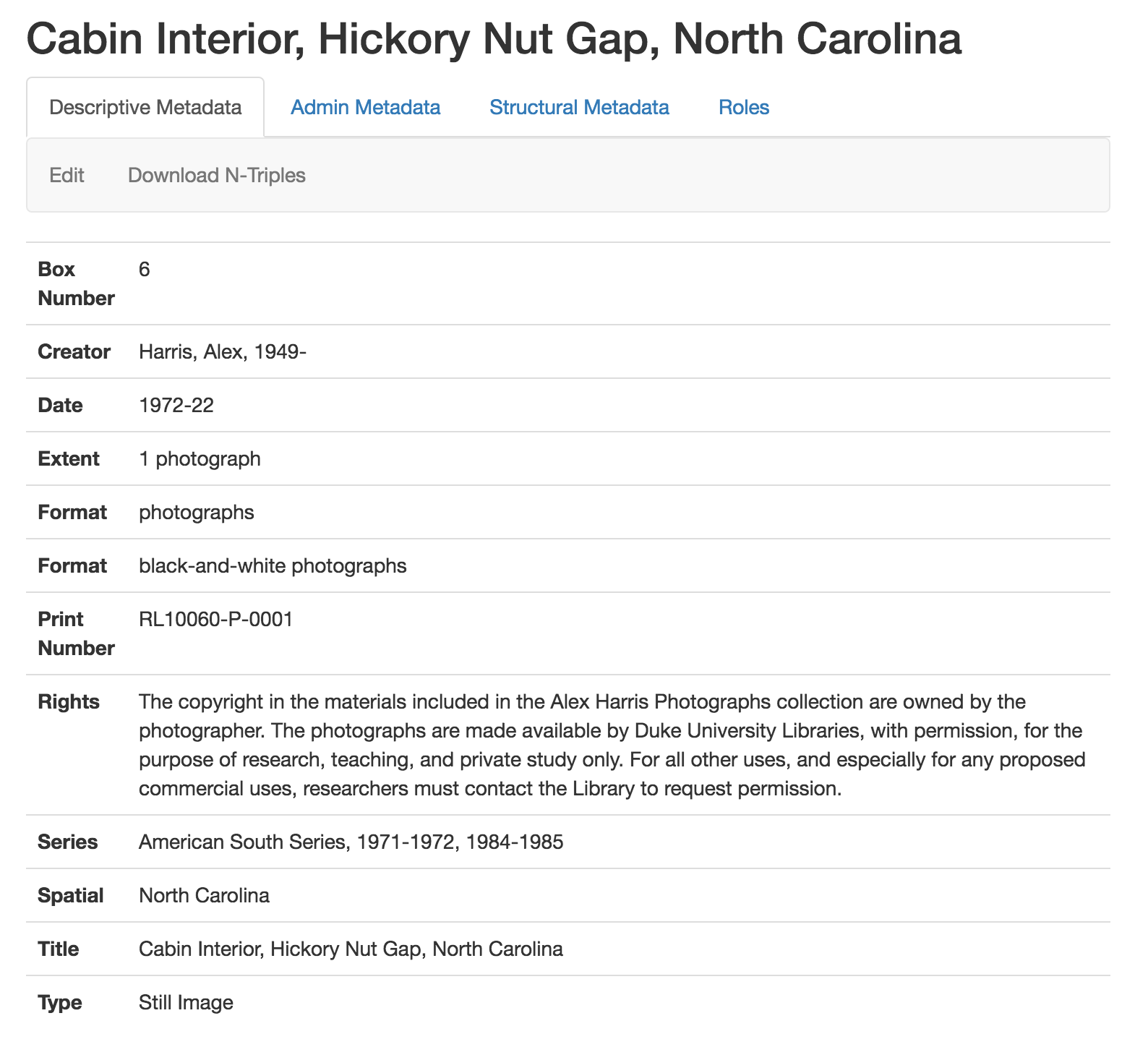

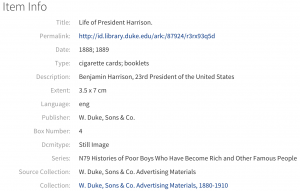

In the metadata record for “Cabin Interior, Hickory Nut Gap, North Carolina” you can see that the date is stored as EDTF:

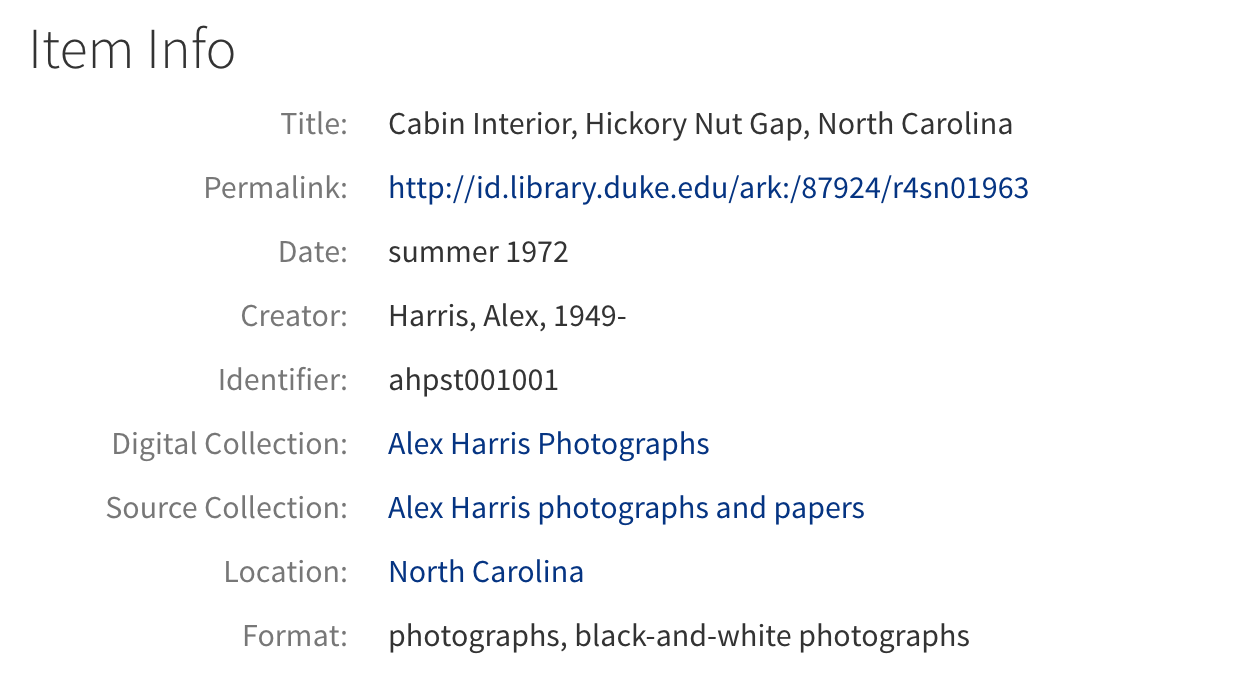

But in the metadata display in the digital repository’s public interface we want to display the date in a more human friendly format:

Because EDTF is machine readable it’s possible to create a set of rules for transforming the dates for display. These rules can get complicated so I wrote a Ruby Gem that masks some of the complexity and adds a humanize method to any EDTF date object. This makes it simple to transform any EDTF encoded date to a human readable string.

> Date.edtf('1972-22').humanize

=> "summer 1972"

Although more work could be done to make it more flexible, the gem is somewhat configurable. For instance, an uncertain date with year precision is encoded in EDTF as “1972~”. The humanize method will by default output this as “circa 1972”:

> Date.edtf('1972~').humanize

=> "circa 1972"

But if for some reason I wanted a different output for an uncertain date with year precision I could modify the edtf-humanize configurations:

> Edtf::Humanize.configuration.approximate_date_prefix = "approximately "

=> "approximately "

> Edtf::Humanize.configuration.year_precision_strftime_format = "%y"

=> "%y"

After changing these settings when I use the humanize method on the same EDTF date I get a different output:

> Date.edtf('1972~').humanize

=> "approximately 72"

> Date.edtf('1972~').humanize

=> "approximately 72"

The humanize method that edtf-humanize adds to EDTF objects makes it much easier to display EDTF encoded date metadata in configurable human friendly formats.

The edtf-humanize gem is available on GitHub and RubyGems.org so it can be included in any Rails project’s gemfile. It should be considered an early release and could use some enhancement for use cases beyond Duke’s Digital Repository where it was originally designed to be used.

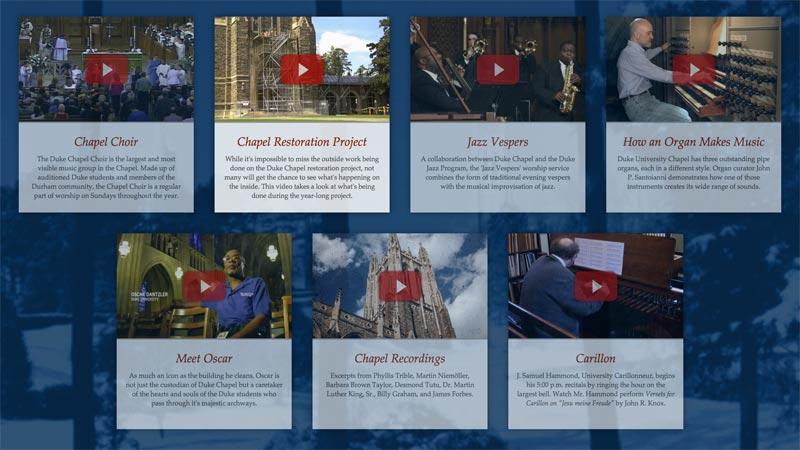

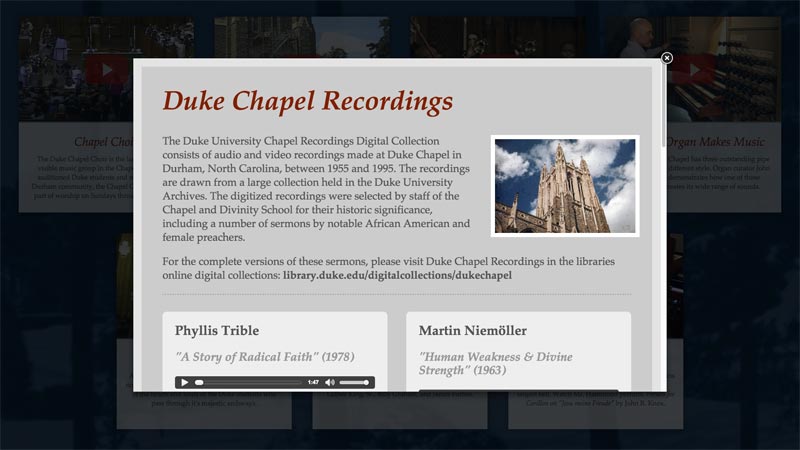

Digital Collections Promotional Card

Digital Collections Promotional Card