Post contributed by Heather McGowan, Marshall T. Meyer Human Rights Archive intern

Hello! I’m Heather McGowan, a second-year student at UNC SILS in the Masters of Library Science Program, and since January I have worked as the Marshall T. Meyer Human Rights Archive Intern at the Rubenstein. I was interested in this internship with the Human Rights Archive because I have always been interested in the ways archival work interacts with social justice and human rights. Working on a collection that revealed the voices of those people who have often been silenced in the record, was my initial interest in this internship, but it has become much more. The work that ICTJ has done to preserve the voices of even the lowest in society, the abused and impoverished, fueled my treatment and work on this collection. Keeping the people at the center has created a collection that reveals the life changing work of ICTJ and its partners, as well as the stories of those who lived, and those who died fighting to see truth and reconciliation.

The International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) founded in 2001, is a global non-profit that works with partners in post-conflict, conflict, and democratic countries to pursue accountability, truth, and reconciliation for massive human right abuses. Through a series of measures including criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations programs, and institutional reforms, ICTJ and its partners strive to bring justice and strength to victims, activists, state leaders, and international policy makers.

When I began working on the collection at the beginning of this year, the ICTJ records consisted of a small fully processed collection of about 40 archival boxes and three large unprocessed accessions of about 160 shipping boxes. Throughout the last six months the collection has begun to take shape and become a powerful testament to ICTJ’s global work.

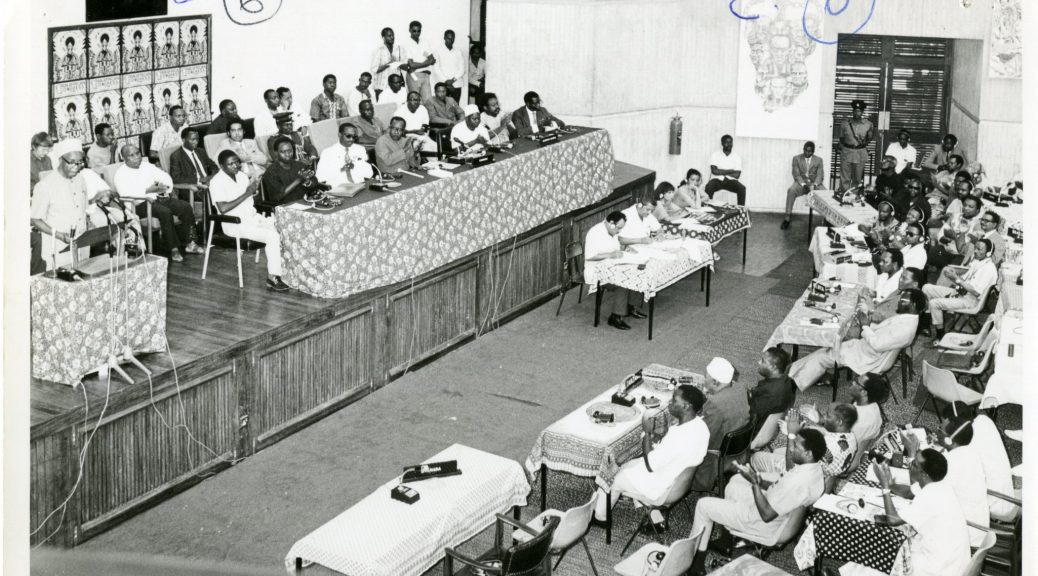

The largest part of the ICTJ records is the Geographic Series. The Geographic Series is comprised of files representing about 100 countries and forms the backbone of ICTJ’s collection. The country files include ICTJ reports, journal articles, publications about governance, rule of law, political stability, reparations, and human rights violations, as well as materials from various country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commissions. These materials are unique to each country and provide insight into the impact ICTJ’s work has on every citizen, from victims to perpetrators, children and women to ex-combatants. These files highlight ICTJ’s mission to support peace, truth, and transparency in each country they work with.

The largest part of the ICTJ records is the Geographic Series. The Geographic Series is comprised of files representing about 100 countries and forms the backbone of ICTJ’s collection. The country files include ICTJ reports, journal articles, publications about governance, rule of law, political stability, reparations, and human rights violations, as well as materials from various country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commissions. These materials are unique to each country and provide insight into the impact ICTJ’s work has on every citizen, from victims to perpetrators, children and women to ex-combatants. These files highlight ICTJ’s mission to support peace, truth, and transparency in each country they work with.

Closely related to the Geographic Series is the Administrative Series, which contains a Staff Files sub-series. These are the files of 16 prominent staff members of ICTJ; former presidents and co-founders, program directors and prosecution unit leaders. The staff files narrate the story of ICTJ from its initial creation to it developing into a strong, influential, global leader in transitional justice. I found one of the highlights of this series to be the files of Priscilla Hayner, one of the co-founders of ICTJ. The initial grants for ICTJ, the architecture plans for their space, the original program units, and the founding mission are all captured in her files. Her work in Ghana, Peru and Sierra Leone is richly detailed with trip reports, mission updates, and research about the best ways to develop transitional justice mechanisms in these countries. Her personal notes, correspondence, writings, and even meeting minutes offer a glimpse into the minds at work in ICTJ.

The other half of the hands-on work of ICTJ is documented in the Program Series. ICTJ is organized into program units that each focus on a different thematic subject, such as gender, as well as into units by region. One of the most robust units is the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) Program. In the past decade, MENA has worked in Iraq as the country transitions from the tyrannical rule of Saddam Hussein into a democratic nation. In 2004, MENA and ICTJ conducted interviews with Iraqi citizens. The transcripts of these interviews are now housed in the ICTJ archive and are filled with details about human rights in the Iraqi context; about what is was like for Iraqis to live in fear of their livelihood and about the hope for reconciliation.

In addition to the hands-on work they do, ICTJ has a robust research unit captured in the Reference and Reports Series. These materials were collected by ICTJ and formerly housed in their Documentation Center and Library at their New York headquarters. The publications include annual reports from human rights NGOs as well as thematic publications about children and women in conflict, displacement, refugees, disappearances, human trafficking, judicial reform, economic issues, security and conflict analysis, genocide and torture, accountability and human rights.

In processing this collection, I was struck by the details of ICTJ’s work. Before working with this collection, I had a vague idea of the work that ICTJ did throughout the world, but in processing, arranging, and describing the ICTJ records, I have come to understand the complexities of trying to bring peace to victims of human rights abuses. The most interesting part of the collection, for me, are the truth and reconciliation commission files. The whole process involved in creating, executing, and continuing the legacy of TRCs is much more complex than I ever conceived. For example, the Rwandan genocide occurred in the 1990s, but the work of the TRC continued well into the mid to late 2000s. By taking statements from victims, disarming and demobilizing former soldiers, creating spaces to have hearings, and putting in place new policies the TRC sought to heal the pain caused by the Rwandan genocide. Another, lesser known genocide, took place in Guatemala over the land to build the Chixoy Dam. From 1980 to 1983 in the village of Rio Negro, about 5,000 indigenous Mayan people were slaughtered and dumped in mass graves by the government. The loss of life and the relative unknown nature of this case made it even more shocking when I uncovered it. ICTJ worked with Mayan communities and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to initiate a human rights case against the Guatemalan military in 2005. This case and the work toward reparations for the people of Rio Negro has faced challenges from the corrupt government of Guatemala, but it has seen success as military dictators have been sentenced to prison. ICTJ engages in complex work often with uncertain outcomes, but it is work that I believe takes the right steps towards healing.

The ICTJ records will be fully processed by the end of the summer, including the audiovisual and electronic records components.