Post contributed by Paula Jeannet, Visual Materials Processing Archivist

This post is part of “An Instant Out of Time: Photography at the Rubenstein Library” blog series

A recently acquired photograph album offers a study of the landscape, culture, and the realities of travel in a remote region in the steppes of Central Asia, through the camera of British Army officer Sir Percy Molesworth Sykes. Charged as acting Consul-General in Chinese Turkestan, now Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China, Sykes had to travel from England to the capital city of Kashgar. In an unusual turn of events for the time, he was accompanied on this arduous overland journey by his sister, Ella Constance Sykes, also a Fellow of the Geographical Society and a well-regarded writer on Iran.

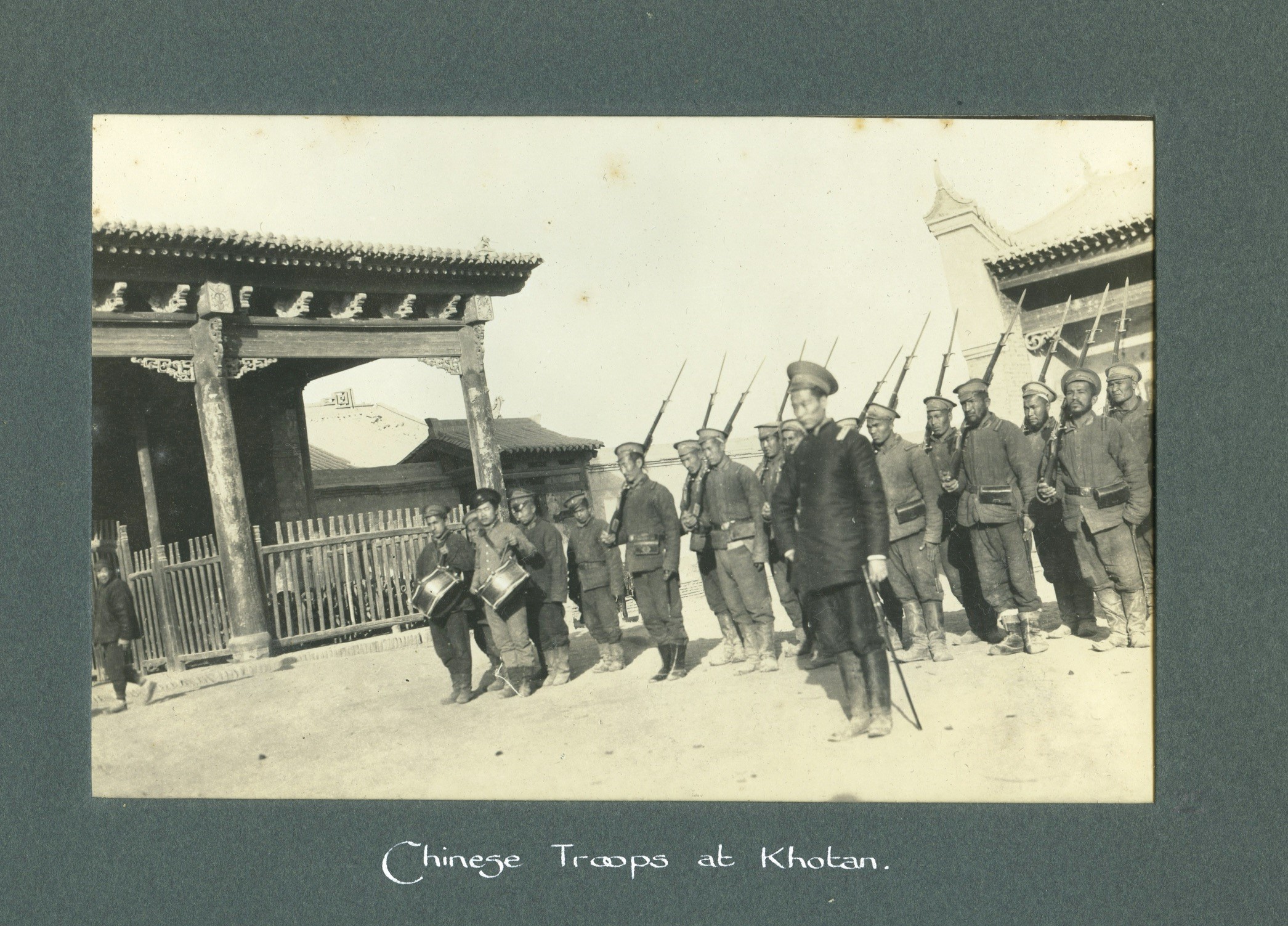

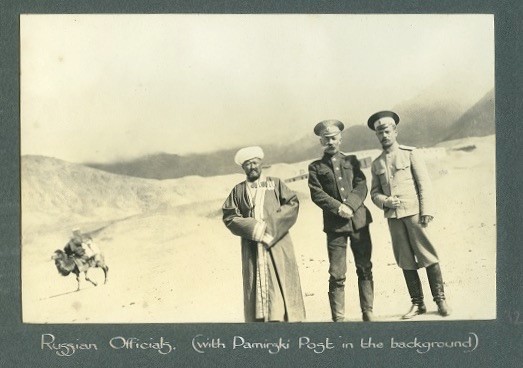

In March 1915, when the two set off for their arduous nine-month journey, World War I was in full tilt, thus their northerly route through Norway. Meanwhile, in Central Asia, after decades of conflict which included the Crimean War, Russians, Turks, English, Chinese, and British Empire troops from India, were still grappling to extend their control over these strategically important regions. Lieutenant Colonel Sykes’ camera recorded the presence of these nationalities.

In researching this collection of photographs, I discovered that brother and sister also recorded their experiences in a co-authored travel memoir, Through deserts and oases of Central Asia (1920, available online); it includes many of the photographs found in the album. To find a written companion piece to a photograph album is a stroke of luck, as with its help I could confirm dates, locations, and a historical context for the photographs found in the album.

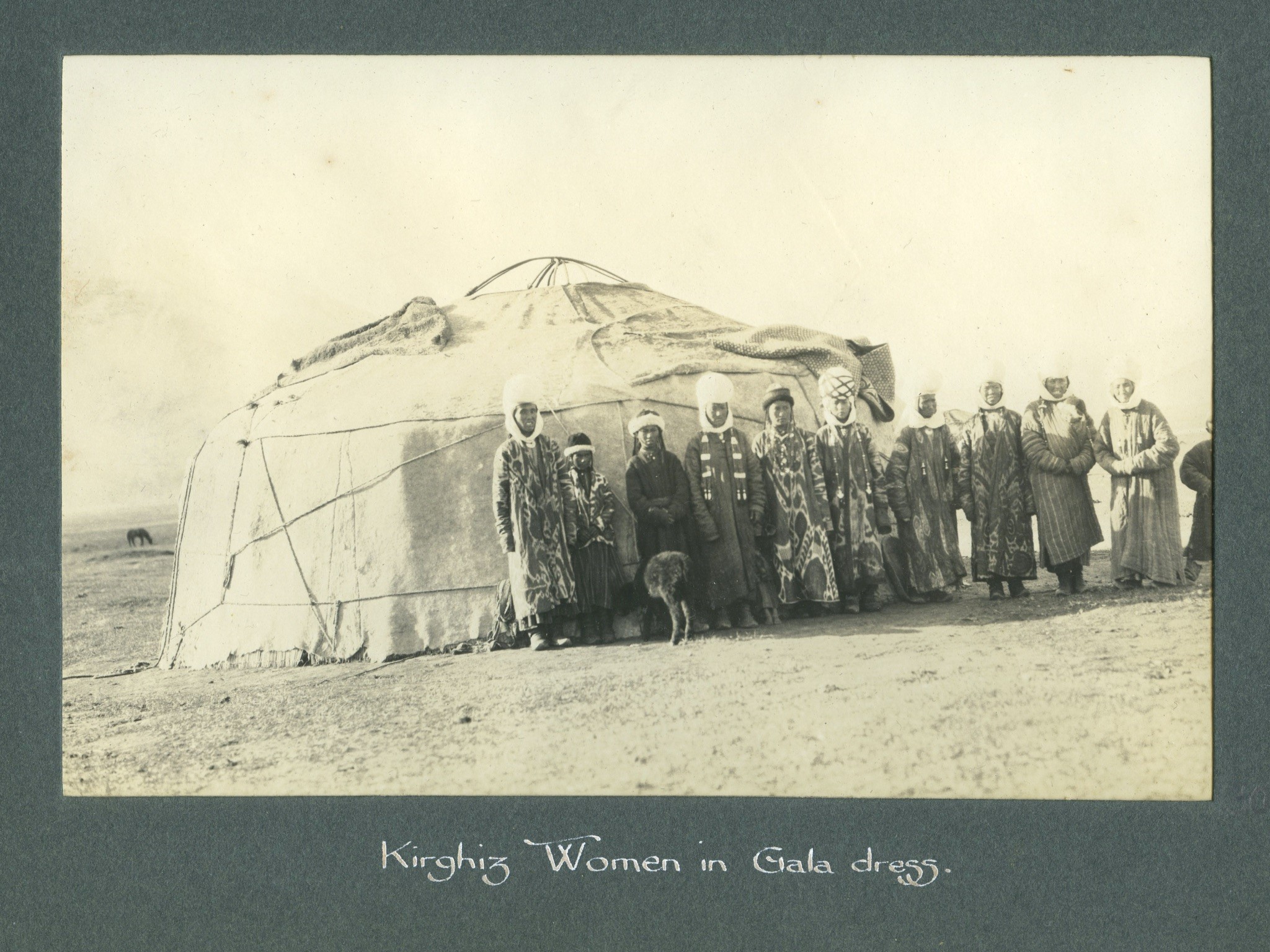

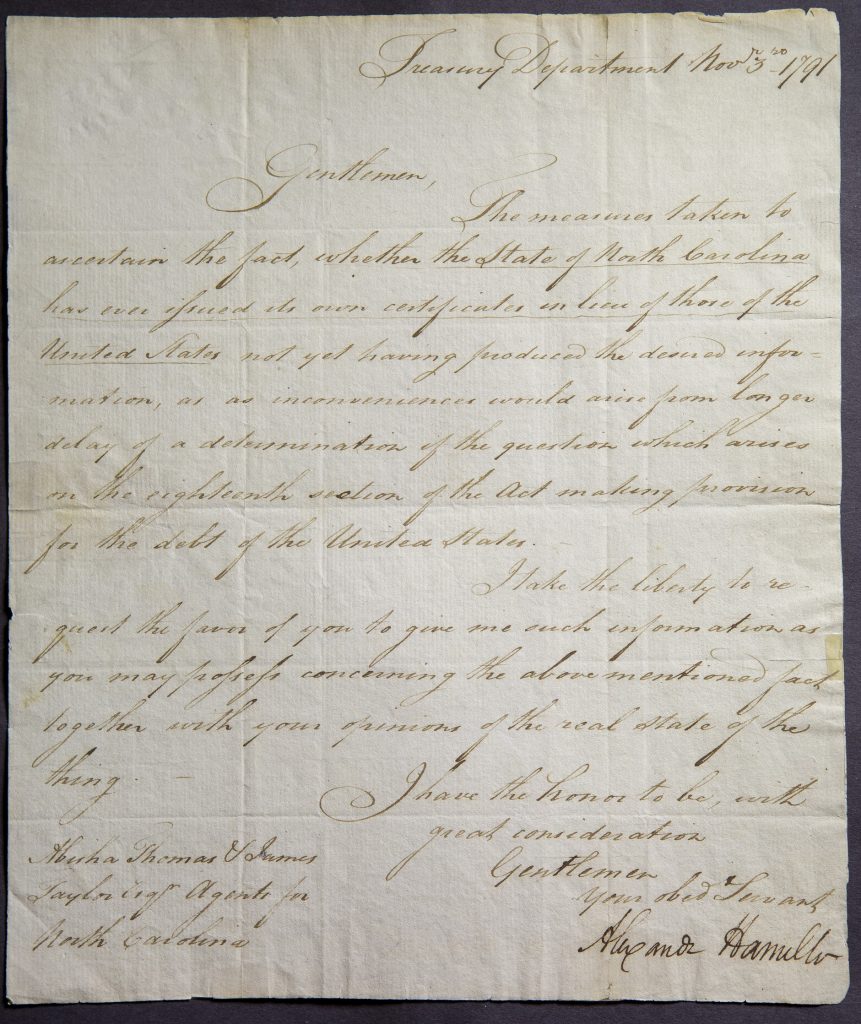

Ella Sykes wrote Part I of the memoir, which describes the journey in vivid detail, and her brother, Part II, which focuses on the region’s geography, history, and culture. In her narrative, Ella occasionally recounts taking photographs of various scenes, such as the image on page 92 of women at a female saint’s shrine. A note in the image index states that “The illustrations, with one exception, are from reproductions of photographs taken by the authors” (emphasis mine); clearly, some of the book’s illustrations are her work. The question arises, did she take any of the images found in the album?

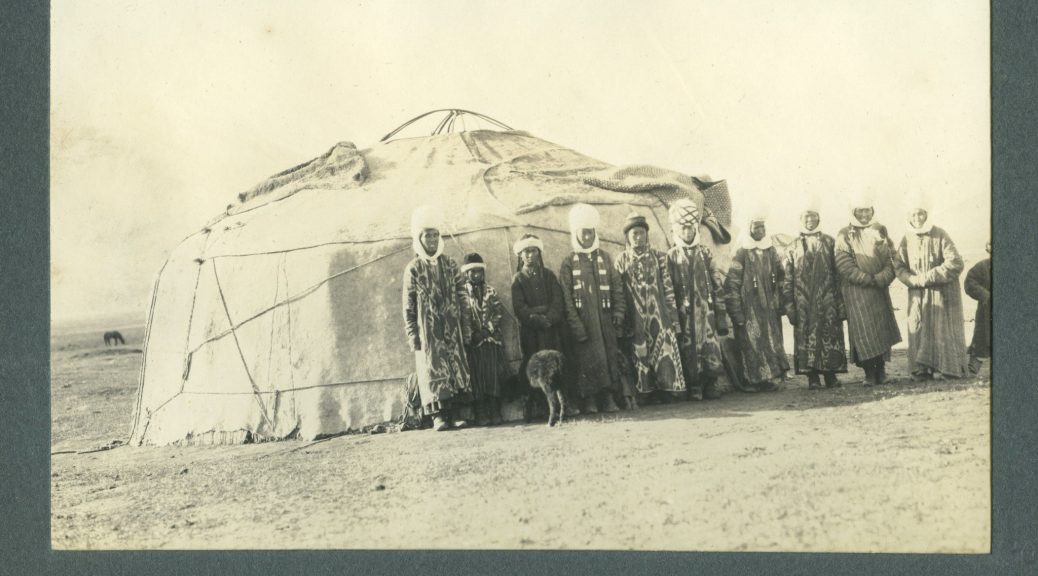

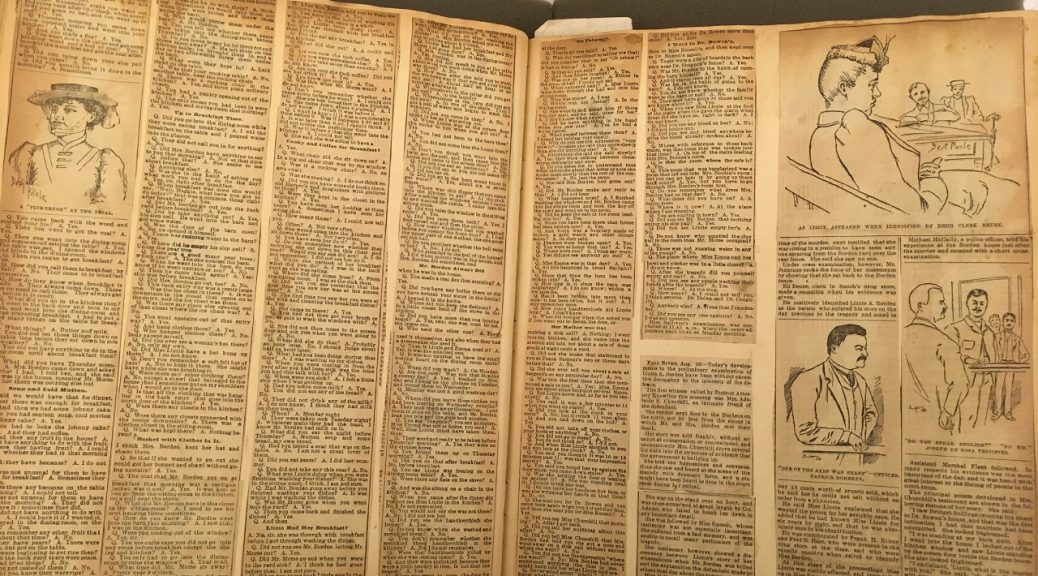

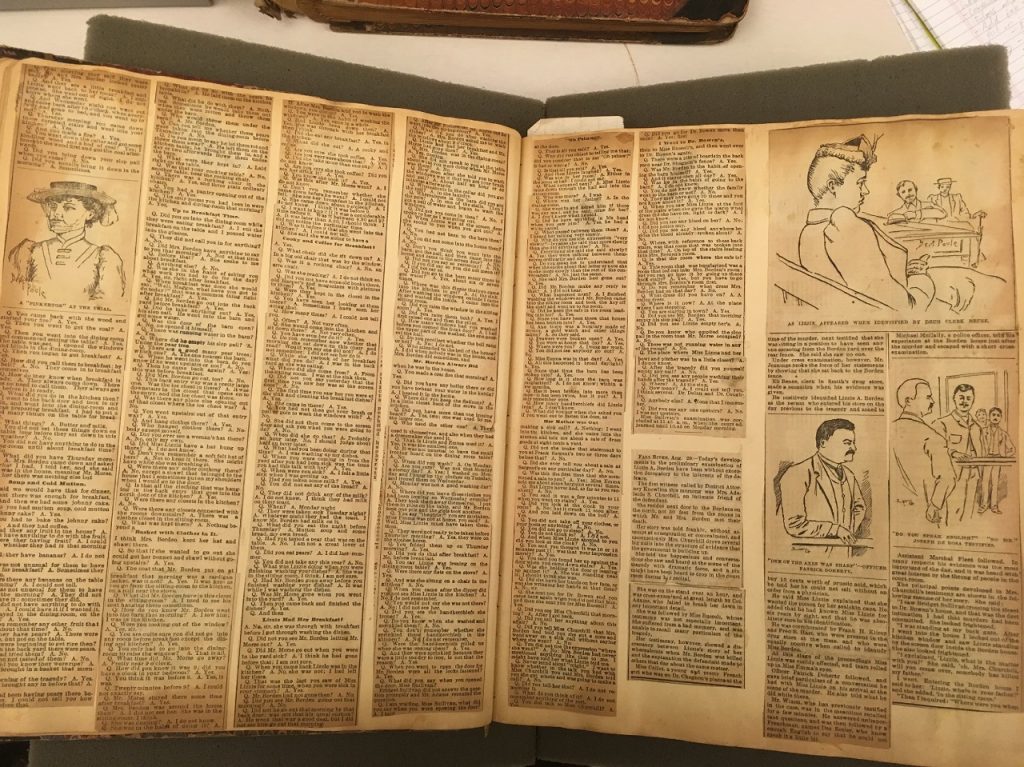

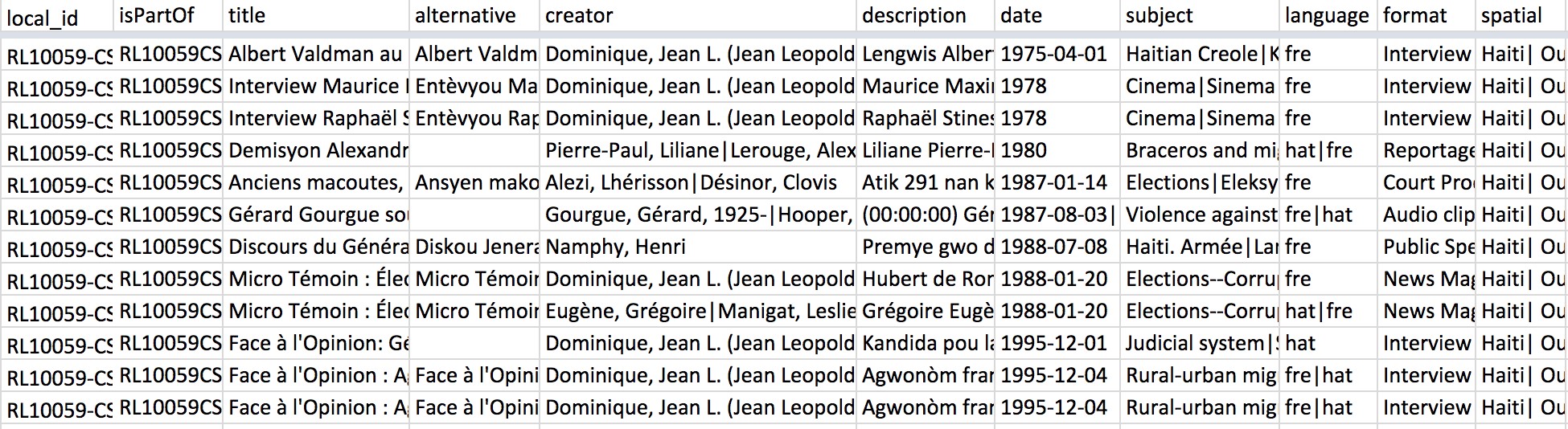

Of the photographs in the album that also appear in the Sykes’ book, several are found in the section written by Ella, leading one to think perhaps she took them, including a different version of this group, found in the album:

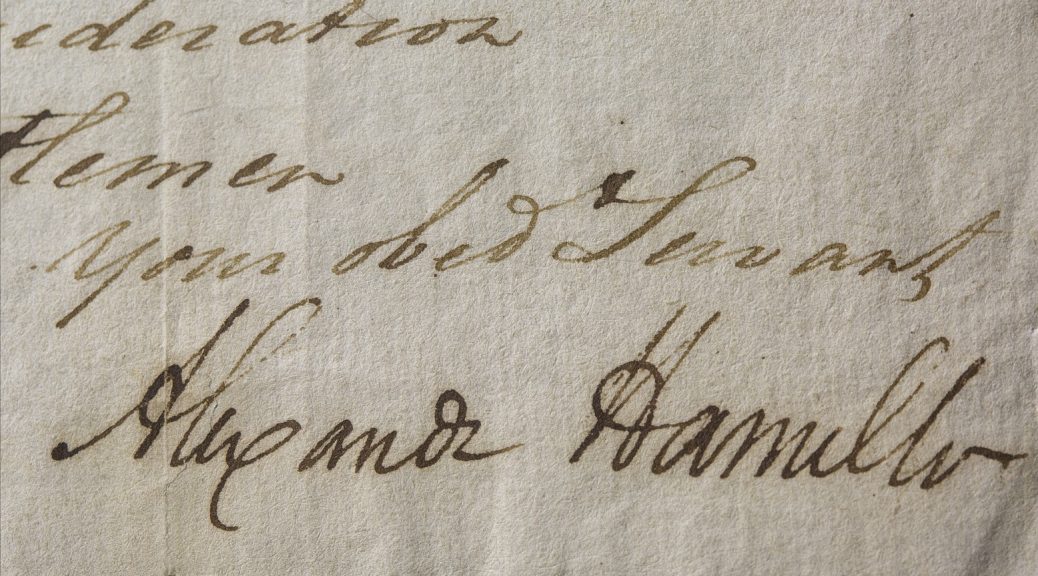

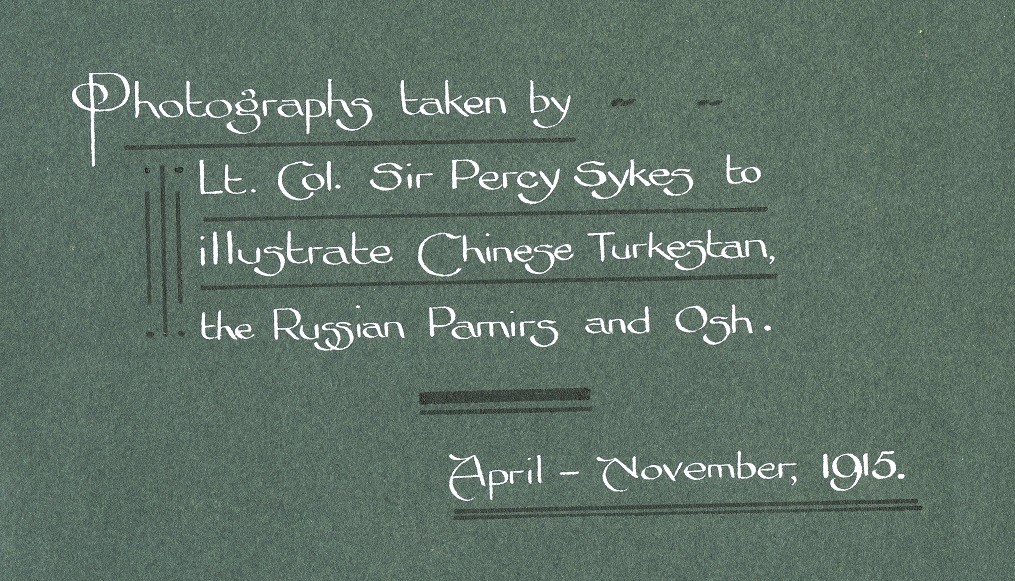

However, the title of the photograph album, handwritten in beautiful calligraphic script, states: “Photographs taken by Lt. Col. Sir Percy Sykes to illustrate Chinese Turkestan, the Russian Pamirs and Osh, April-November, 1915.”

With this title in hand and my cataloging hat on, and without firm evidence of Ella’s hand in the album’s images, I officially record Sir Percy Sykes as the album’s sole creator.

Through researching the context for Percy Sykes’ photograph album (a copy of which is also held by the British Library), I learned a bit about the history of the region and of his role in the administration of British affairs. I was also serendipitously introduced to Ella Sykes. Even though in her fifties when she traveled, she clearly had great stamina as a horsewoman and adventurer, and was a keen observer of the people, landscapes, and animals she encountered. Sir Percy writes in the book’s preface: “To my sister belongs the honour of being the first Englishwoman to cross the dangerous passes leading to and from the Pamirs, and, with the exception of Mrs. Littledale, to visit Khotan.” (p. vi) Ella Sykes was a founding member of the Royal Central Asian Society and a member of the Royal Geographical Society as well. She died in 1939 in London, while her brother Percy died in 1945, also in London.

For more information about the photograph album, see the collection guide. The album is non-circulating but is available to view in the Rubenstein Library reading room. It joins other Rubenstein photography collections documenting the history of adjacent regions in the Middle East, Central Asia, Russia, India, and China.

Additional links:

Photograph portrait, reportedly of Ella Sykes, from the Long Riders Guild of travel narratives.

Some biographical information was taken courtesy of: Denis Wright, “SYKES, Ella Constance,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2008, viewed December 10, 2018, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sykes-ella-constance