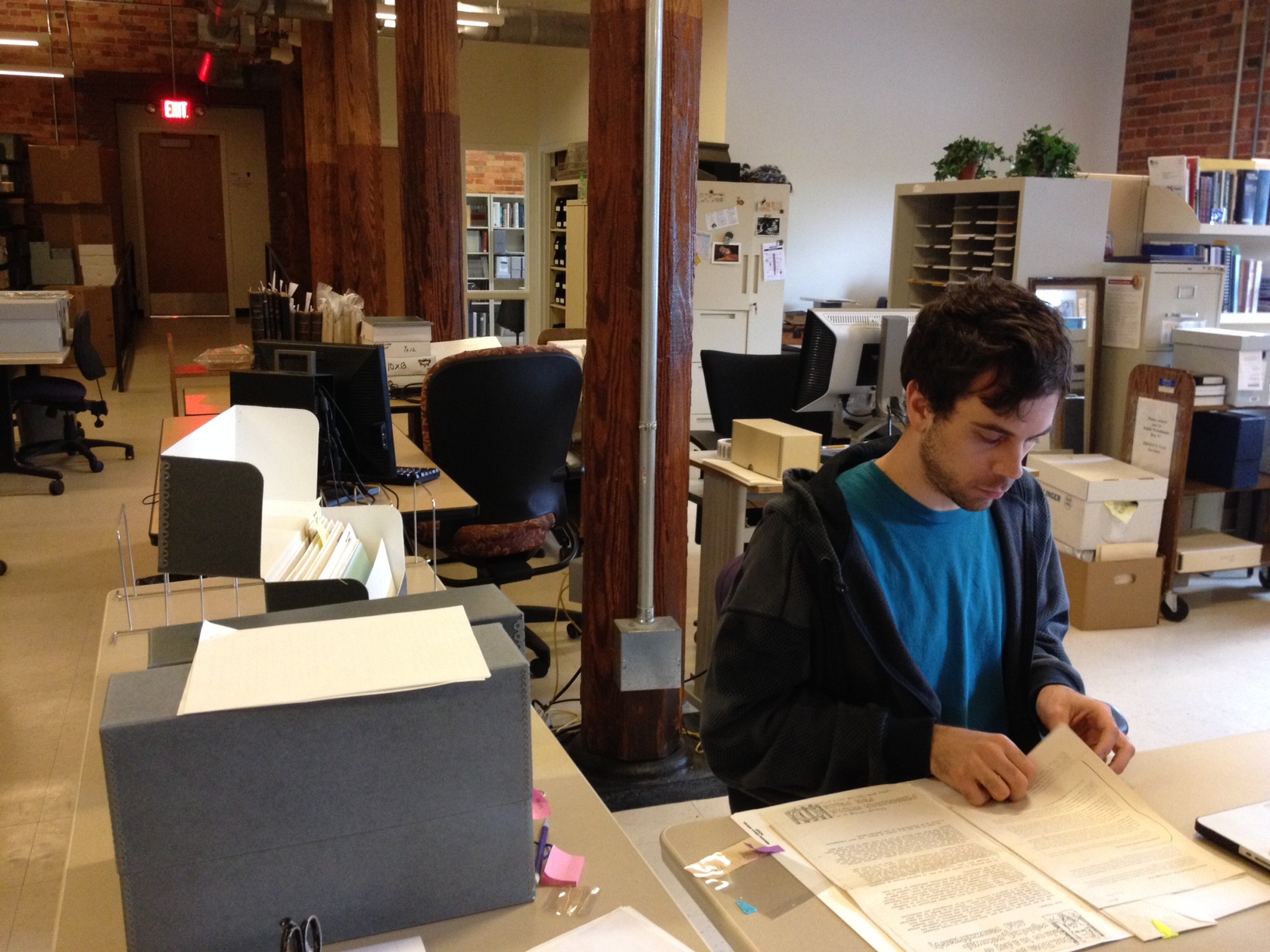

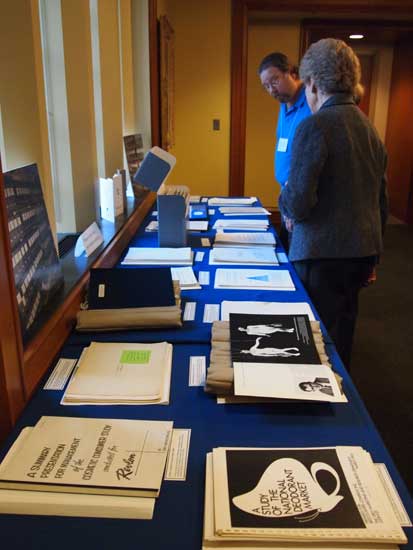

On Thursday, November 7th, twenty of Al Achenbaum’s family and close friends joined Duke library staff and faculty in a ceremony to dedicate his papers as part of the John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History. In a series of comments given by Hartman Center staff, Achenbaum’s papers were lauded for their unique insight into building brand equity, strategic marketing planning, maximizing advertising agency-client relationships, and using systematic quantitative research as a guide to effective decision-making.

Over a remarkable 60-year career, he advised leading global marketers, including Procter & Gamble, GE, Toyota and Nestlé, on how to use marketing tools to improve the economic value of their businesses. He held senior executive positions at four major advertising agencies in New York, and was chairman of a series of leading marketing consulting firms which provided over 150 companies with systematic tools for addressing complex business challenges.

This 233-box collection will enrich the experiences of many students and scholars interested in the evolution of the advertising industry in the second half of the 20th century or the career of Al Achenbaum, known to many as the “Einstein of Advertising” and one of Advertising Age’s 100 most influential advertising people of the 20th century. Al’s son, Jon Achenbaum, described his father as the reason he started his own career in marketing, applying many of the marketing innovations that Al brought into the business world and read two passages from Al’s upcoming book.

Rounding out the event were remarks by Al Achenbaum himself, in which he stated that “marketing is the single most important driver of our modern economy” and that it will “continue to play a critical role in economic success – both in the U.S. and abroad.” He expressed his gratitude to his family and friends for supporting him throughout his life and career and expressed his enthusiasm for donating his papers to Duke and the Hartman Center.

To top off the ceremony, he announced that he is endowing the Hartman Center’s travel grant program, which will be named the Alvin A. Achenbaum Travel Grants. These travel grants will enable students and scholars to come from afar to use Hartman Center collections as part of their research each year. Since Achenbaum is in many ways a scholar of advertising and marketing himself, this is a wonderful way to continue his legacy in perpetuity.

Post contributed by Jackie Reid Wachholz, director of the John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History.