Way back in spring 2023, we wrote about the emergence of ChatGPT on Duke’s campus. The magical tool that could help, “Write papers! Debug Code! Create websites from thin air! Do your laundry!” By 2026, AI can do most of those things (well…maybe not your laundry). But one problem we highlighted back then persists today: LLMs still make stuff up.

ChatGPT on Duke’s campus. The magical tool that could help, “Write papers! Debug Code! Create websites from thin air! Do your laundry!” By 2026, AI can do most of those things (well…maybe not your laundry). But one problem we highlighted back then persists today: LLMs still make stuff up.

When I talk to Duke students, many describe first-hand encounters with AI hallucinations – plausible sounding, but factually incorrect AI-generated info. A 2025 research study of Duke students found that 94% believe Generative AI’s accuracy varies significantly across subjects, and 90% want clearer transparency about an AI tool’s limitations. Yet despite these concerns, 80% still expect AI to personalize their own learning within the next five years. Students feel they don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater when these tools can break down complex topics, summarize dense course readings, or turn a messy pile of class notes into a coherent study outline. This tension between AI’s usefulness and its unreliability raises an obvious question: if the newest “reasoning models” are smarter and more precise, why do hallucinations persist?

Below are four core reasons.

1. Benchmark tests for LLMs favor guessing over IDK

You’ve probably seen the headlines: the latest version of [insert AI chatbot here] has aced the MCAT, crushed the LSAT, and can perform PhD-level reasoning tasks. Impressive as this sounds, many of the benchmark evaluation tests for LLMs reward guessing over acknowledging uncertainty – as explained in Open AI’s post, Why Language Models Hallucinate. This leads to the question: why can’t AI companies just design models that say “I don’t know”? The short answer is that today’s LLMs are trained to produce the most statistically likely answer, not to assess their own confidence. Without an evaluation system that rewards saying “I don’t know” models will default to guessing. But even if we fix the benchmarks, another problem remains: the quality of the information LLMs train on is often pretty bad.

PhD-level reasoning tasks. Impressive as this sounds, many of the benchmark evaluation tests for LLMs reward guessing over acknowledging uncertainty – as explained in Open AI’s post, Why Language Models Hallucinate. This leads to the question: why can’t AI companies just design models that say “I don’t know”? The short answer is that today’s LLMs are trained to produce the most statistically likely answer, not to assess their own confidence. Without an evaluation system that rewards saying “I don’t know” models will default to guessing. But even if we fix the benchmarks, another problem remains: the quality of the information LLMs train on is often pretty bad.

2. Training data for LLMs is riddled with inaccuracies, half-truths, and opinions

The principle of GIGO (Garbage In, Garbage Out) is critical to understanding the hallucination problem. LLMs perform well when a fact appears frequently and consistently in its training data. For example, because the capital of Peru (=Lima) is widely documented, an LLM can reliably reproduce that fact. Hallucinations arise when the data is more sparse, contradictory, or low-quality. Even if we could minimize hallucination, we’d be relying on the assumption that the underlying training data is trustworthy. And remember: LLMs are trained on vast swaths of the open web. Reddit threads, YouTube conspiracy videos, hot-takes on personal blogs, and evidence-based academic sources all sit side-by-side in the training data. The LLM doesn’t inherently know which sources are credible. So if a false claim appears often enough (ex. The Apollo moon landing was a hoax!) – an LLM might confidently repeat it, even though the claim has been thoroughly debunked.

understanding the hallucination problem. LLMs perform well when a fact appears frequently and consistently in its training data. For example, because the capital of Peru (=Lima) is widely documented, an LLM can reliably reproduce that fact. Hallucinations arise when the data is more sparse, contradictory, or low-quality. Even if we could minimize hallucination, we’d be relying on the assumption that the underlying training data is trustworthy. And remember: LLMs are trained on vast swaths of the open web. Reddit threads, YouTube conspiracy videos, hot-takes on personal blogs, and evidence-based academic sources all sit side-by-side in the training data. The LLM doesn’t inherently know which sources are credible. So if a false claim appears often enough (ex. The Apollo moon landing was a hoax!) – an LLM might confidently repeat it, even though the claim has been thoroughly debunked.

3. LLMs aim to please (because that’s what we want them to do)

When ChatGPT-4o launched, OpenAI was quickly criticized for the model’s unusually high level of sycophancy. AI sycophancy being the tendency an LLM has to validate and praise users even when their ideas are pretty ridiculous (like the now-famous soggy cereal cafe concept). OpenAI dialed back the sycophancy, but the incident revealed something fundamental: LLMs tell us what we want to hear. Because these systems learn from human feedback, they’re reinforced to sound helpful, friendly, and affirming. They’ve learned that people prefer a “digital Yes Man.” After all, if ChatGPT wasn’t so validating, would you really keep coming back? Probably not. This tension between the very behaviors that make them fun to use can make them overconfident, over-agreeable, and more prone to innacuracies or hallucination.

model’s unusually high level of sycophancy. AI sycophancy being the tendency an LLM has to validate and praise users even when their ideas are pretty ridiculous (like the now-famous soggy cereal cafe concept). OpenAI dialed back the sycophancy, but the incident revealed something fundamental: LLMs tell us what we want to hear. Because these systems learn from human feedback, they’re reinforced to sound helpful, friendly, and affirming. They’ve learned that people prefer a “digital Yes Man.” After all, if ChatGPT wasn’t so validating, would you really keep coming back? Probably not. This tension between the very behaviors that make them fun to use can make them overconfident, over-agreeable, and more prone to innacuracies or hallucination.

4. Human language (and how we use it) is complicated

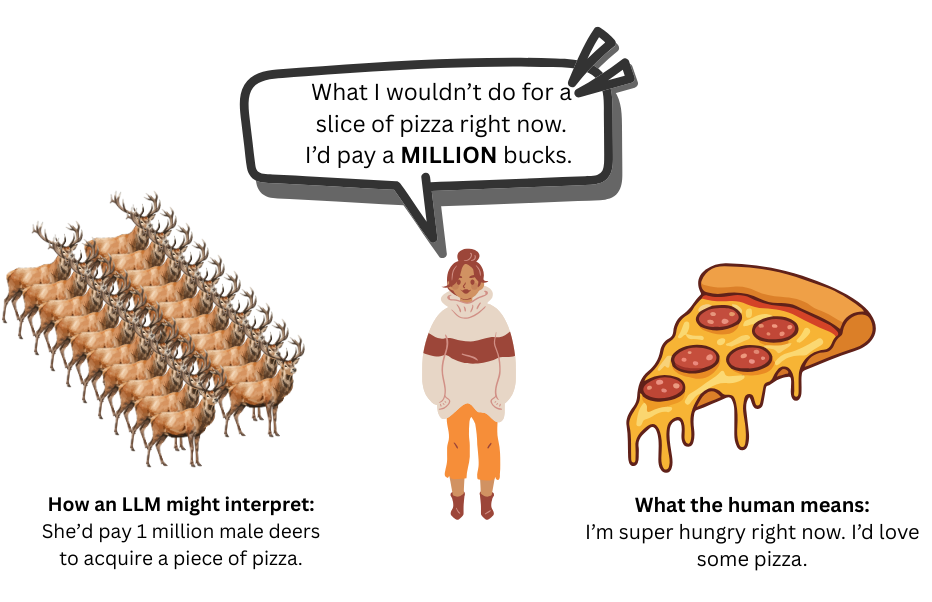

LLMs are excellent at parsing syntax and analyzing semantics, but human communication requires much more than grammar. In linguistics, the concept of pragmatics refers to how context, intention, tone, background knowledge, and social norms shape meaning. This is where LLMs struggle. They don’t truly understand implied meanings, sarcasm, emotional nuance or unspoken assumptions. LLMs use math (or statistical pattern matching) to predict the probable next word or idea. When that educated guess doesn’t align with the intended meaning, hallucinations may be more likely to occur.

linguistics, the concept of pragmatics refers to how context, intention, tone, background knowledge, and social norms shape meaning. This is where LLMs struggle. They don’t truly understand implied meanings, sarcasm, emotional nuance or unspoken assumptions. LLMs use math (or statistical pattern matching) to predict the probable next word or idea. When that educated guess doesn’t align with the intended meaning, hallucinations may be more likely to occur.

Example to illustrate how linguistic meaning and literal meaning could be challenging for an LLM to interpret:

TL; DR – So … why are LLMs still hallucinating?

- They’re evaluated using benchmarks that reward confident answers over accurate ones.

- They’re trained on internet data full of contradictions, misinformation, and opinions.

- They’re reinforced (by humans) to be friendly and engaging – sometimes to a fault.

- They still can’t grasp the contextual, messy nature of human language.

AI will keep improving and getting better, but trustworthiness isn’t just a technial problem – it’s a design, data, and human-behavior problem. By understanding how LLMs work, staying critically aware of their limitations, and double-checking anything that seems off, you’ll strengthen your AI fluency and make smarter use of the technology.

Want to boost your AI fluency? Check out these Duke resources:

- Duke Engineering Professor Brinnae Bent’s YouTube series, AI4People Who Hate Math.

- Duke’s Academic Resource Center’s, Brain-first AI Learning Tips.

- Duke Libraries’ AI Ethics Learning Toolkit for teaching ideas on topics like, Trust and Bias.

References & Further Reading

- Duke University. (2025). AI student survey. Conducted by Duke students, Barron Brothers (T ’26) and Emma Ren (T ’27).

On AI sycophancy:

- Chedraoui, K. (2025, October 1). The hidden dangers of the digital “yes man”: How to push back against sycophantic AI. CNET. Overview of AI sycophancy. Includes quotes from Duke Professor Brinnae Bent.

- Chedraoui, K. (2025, November 5). This AI chatbot is built to disagree with you, and it’s better than ChatGPT. CNET. A look at a bot to combat AI sycophancy from Duke’s Professor Bent and the TRUST lab.

- Hill, K., & Valentino-DeVries, J. (2025, November 23). What OpenAI did when ChatGPT users lost touch with reality. The New York Times. NYTimes piece about the sycophancy issue with ChatGPT-4o.

On AI hallucination:

- OpenAI. Why language models hallucinate. (2025, December 8).

- Kalai, A. T., Nachum, O., Vempala, S. S., & Zhang, E. (2025). Why language models hallucinate. arXiv. This is the lengthier research paper that the above blog piece is based on.

On pragmatics in LLMs:

- Ma, B., Li, et al. (2025). Pragmatics in the era of large language models: A survey on datasets, evaluation, opportunities and challenges. Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 8679–8696. This paper covers the concept of linguistics and pragmatics in LLMs.

Special thanks to Brinnae Bent, Mary Osborne, and Aaron Welborn for reviewing the post!

Nitin Luthra (he/him) is a doctoral researcher at the

Nitin Luthra (he/him) is a doctoral researcher at the

Meet Emilie Menzel

Meet Emilie Menzel

Ann Chapman Price is a historian of Christian spirituality, with a focus on medieval and early modern European theology and society. She is interested in the development of Christian mysticism throughout the tradition, the theology of medieval women’s religious texts, and the intersections of Christian spirituality with issues of race, sex, and gender. Ann’s research in the digital humanities primarily focuses on the study of texts and their representation and scholarly editing in the digital realm.

Ann Chapman Price is a historian of Christian spirituality, with a focus on medieval and early modern European theology and society. She is interested in the development of Christian mysticism throughout the tradition, the theology of medieval women’s religious texts, and the intersections of Christian spirituality with issues of race, sex, and gender. Ann’s research in the digital humanities primarily focuses on the study of texts and their representation and scholarly editing in the digital realm.

The latest installment in the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) series highlighting digital scholarship support at ARL member libraries features the work of the Duke University Libraries.

The latest installment in the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) series highlighting digital scholarship support at ARL member libraries features the work of the Duke University Libraries.

Ben Fino-Radin is a New York based media archaeologist and conservator of born-digital and computer-based works of contemporary art. At Rhizome at the New Museum, he leads the preservation and curation of the ArtBase, one of the oldest and most comprehensive collections of born-digital works of art. He is also in practice in the conservation department of the Museum of Modern Art, managing the museum’s repository for digital assets in the collection, as well as contributing to media conservation projects. He is near completion of an MFA in digital arts and MS in Library and Information Science at Pratt Institute, with a BFA from Alfred University.

Ben Fino-Radin is a New York based media archaeologist and conservator of born-digital and computer-based works of contemporary art. At Rhizome at the New Museum, he leads the preservation and curation of the ArtBase, one of the oldest and most comprehensive collections of born-digital works of art. He is also in practice in the conservation department of the Museum of Modern Art, managing the museum’s repository for digital assets in the collection, as well as contributing to media conservation projects. He is near completion of an MFA in digital arts and MS in Library and Information Science at Pratt Institute, with a BFA from Alfred University.

Starting this semester, Duke University faculty, students, and staff can request to have certain public domain books scanned on demand. If a book is published before 1923* and located in the Perkins, Bostock, Lilly, or Music Library or in the Library Service Center (LSC), a green “Digitize This Book” button (pictured here) will appear in its online catalog record. Clicking on this button starts the request.

Starting this semester, Duke University faculty, students, and staff can request to have certain public domain books scanned on demand. If a book is published before 1923* and located in the Perkins, Bostock, Lilly, or Music Library or in the Library Service Center (LSC), a green “Digitize This Book” button (pictured here) will appear in its online catalog record. Clicking on this button starts the request.