Written by Will Shaw on behalf of the Library Summer Camp organizing committee.

From June to August, most students may be off campus, but summer is still a busy time at Duke Libraries. Between attending conferences, preparing for fall semester, and tackling those projects we couldn’t quite fit into the academic year, Libraries staff have plenty to do. At the same time, summer also means a lull in many regular meetings — as well as remote or hybrid work schedules for many of us. Face-to-face time with our colleagues can be hard to come by. Lucky for all of us, July is when Libraries Summer Camp rolls around.

What is Summer Camp?

Summer Camp began in 2019 with two major goals: to foster peer-to-peer teaching and learning among Libraries staff, and to help build connections across the many units in our organization. Our staff have wide-ranging areas of expertise that deserve a showcase, and we could use a little time together in the summer. Why not try it out?

The first Summer Camp was narrowly focused on digital scholarship and publishing, and we solicited sessions from staff who we knew would already have instructional materials in hand. The response from both instructors and participants was enthusiastic; we ultimately brought staff together for 21 workshops over the course of a week in late summer.

The pandemic scuttled plans for 2020 and 2021 Summer Camps, but we relaunched in 2022 with the theme “Refresh!”—a conscious attempt to help us reconnect (in person, when possible!) after months of physical distance. Across the 2019, 2022, and 2023 iterations, Libraries Summer Camp has brought over 60 workshops to hundreds of attendees.

What did we learn this year?

Professional development workshops are still at the core of Summer Camp. But over the years, Camp has evolved to include a wider range of personal enrichment topics. The evolution has helped us find the right tone: learning together, as always, but having fun and focusing on personal growth, too.

For example, participants in this year’s Summer Camp could learn how to crochet or play the recorder, explore native plants, create memes, or practice Koru meditation. In parallel with those sessions, we had opportunities to discover the essentials of data visualization, try out platforms such as AirTable, discuss ChatGPT in libraries, learn fundraising basics, and improve our group discussions and decision-making, to name just a few.

Like any good Summer Camp, we wrapped things up with a closing circle. We shared our lessons learned, favorite moments, and hopes for future camps over Monuts and coffee.

What’s next?

After its third iteration, Summer Camp is starting to feel like a Duke Libraries tradition. Over 100 Libraries staff came together to teach with and learn from each other in 25 sessions this year. Based on both attendance and participant feedback, that’s a success, and it’s one we’d like to sustain. It’s hard not to feel excited for Summer Camp 2024.

As we look ahead, the organizing committee—Angela Zoss, Arianne Hartsell-Gundy, Kate Collins, Liz Milewicz, and Will Shaw—will be actively seeking new members, ideas for Summer Camp sessions, and volunteers to help out with planning. We encourage all Libraries staff to reach out and let us know what you’d like to see next time around!

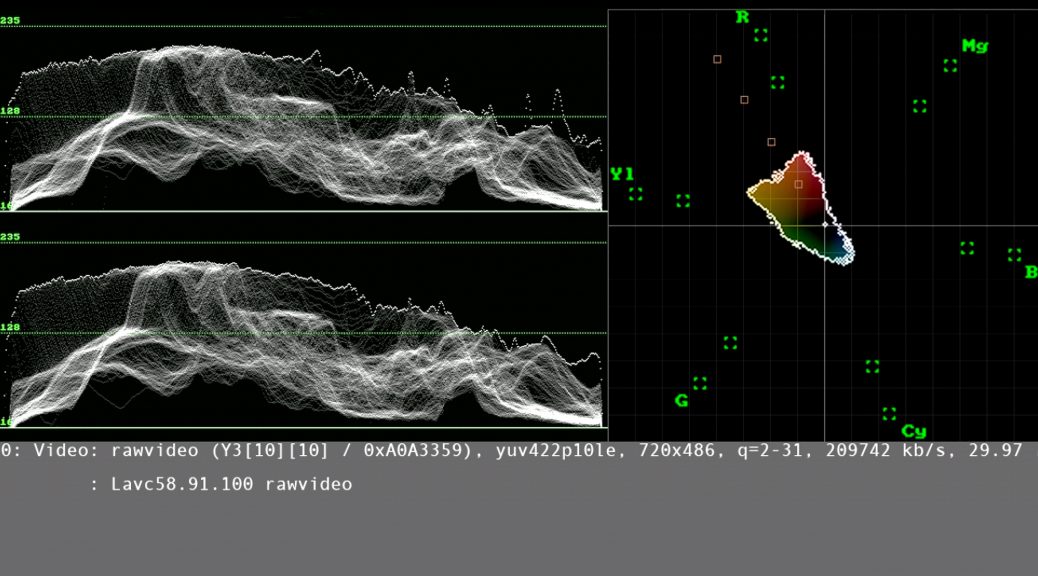

Once the shot is in focus and appropriately bright, we will check our colors against an X-Rite ColorChecker Classic card (see the photo on the left) to verify that our camera has a correct white balance.

Once the shot is in focus and appropriately bright, we will check our colors against an X-Rite ColorChecker Classic card (see the photo on the left) to verify that our camera has a correct white balance.