Post contributed by Erin Ryan, Drill Intern for the Duke University Archives.

When I first signed up to do a Rubenstein Test Kitchen blog post, my plan was to do something from an early-to-mid 20th-century vegetarian cookbook in our collections. I’ve been a vegetarian since the mid-’90s.

But then, as I was browsing our library catalog, I came across 401 Party and Holiday Ideas from ALCOA (Aluminum Company of America, 1971) in our Nicole Di Bona Peterson Collection of Advertising Cookbooks. I was intrigued; my grandfather—my dad’s father—worked for ALCOA for about 35 years, until his retirement in the early ’80s.

But then, as I was browsing our library catalog, I came across 401 Party and Holiday Ideas from ALCOA (Aluminum Company of America, 1971) in our Nicole Di Bona Peterson Collection of Advertising Cookbooks. I was intrigued; my grandfather—my dad’s father—worked for ALCOA for about 35 years, until his retirement in the early ’80s.

Pretty soon, I was hooked.

This amazing book features the creations of one Conny von Hagen, who worked as a designer for ALCOA, still one of the largest producers of aluminum.

Conny was also behind 1959’s Alcoa’s Book Of Decorations: A Year-Round Treasury of Easy-to-do Decorations for Holidays and Special Occasions. According to the timeline on their website, ALCOA introduced aluminum foil to the U.S. in 1910—you can see some “Alcoa Wrap” next to Conny in the picture below. This introductory page also explains that her designs appeared on TV, in newspapers and in magazines.

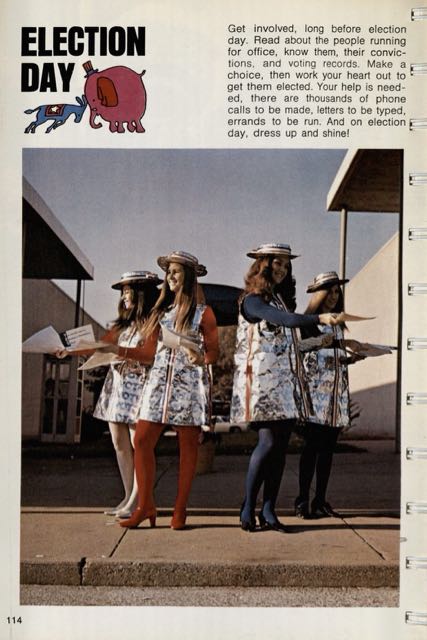

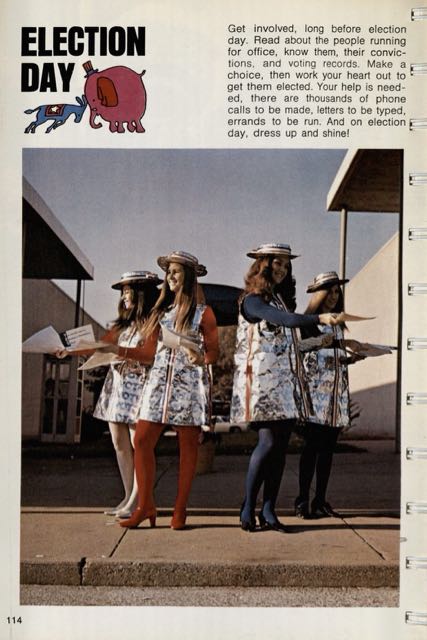

401 Party and Holiday Ideas from ALCOA has ideas for 24 separate occasions, from Christmas and Hanukkah to “Teen-Age Party” and Election Day.

For this post, I decided to make (1) a food recipe; (2) a foil creation.

The food: Kerry Cake

I made Irish Apple Cake, or Kerry Cake, from the “Saint Patrick’s Day” chapter of 401 Party and Holiday Ideas. Criteria: It had to be vegetarian, and it had to be easy (I was pressed for time). I also wanted to serve it at my Easter family gathering. I didn’t like any of the Easter recipes, though. So a quick look through the rest of the book, and I settled on this:

My ancestry is mostly Irish, but I did not know anything about Kerry Cake until I read here that it is a traditional Irish apple bread that was baked in an iron cooking pot called a bastible, hung over the fire.

But this 1971 recipe just called for an 8-inch cake pan in a regular oven, and that’s what I used. I was making this in my mom’s kitchen, so I got to use the sifter that had belonged to her mom. Mom told me we had relatives from County Kerry, too.

But this 1971 recipe just called for an 8-inch cake pan in a regular oven, and that’s what I used. I was making this in my mom’s kitchen, so I got to use the sifter that had belonged to her mom. Mom told me we had relatives from County Kerry, too.

I’m a pretty laissez-faire cook, in general. So I didn’t mind that the recipe didn’t specify what kind of apples to use, how big to cut the pieces, etc. I went for Granny Smith. They were pretty huge apples, so Mom and I decided I should just use two, to equal the “three medium” the recipe called for.

In all, it took me about 50 minutes to grate the lemon rind, cut up the apple, and put the batter together. I greased the pan with butter, baked it exactly according to instructions (30 minutes at 375), and it came out perfectly.

I whipped some heavy cream and served this cake at our Easter dinner. I was afraid it would be bland without spices, or that the lemon would taste strange. But it was delicious. Moist, not too sweet, and the lemon was exactly the right amount to accentuate the apples and butter. There were six adults at dinner, including a guest from Colombia, and everybody loved the Kerry Cake. Almost the whole cake was gone by the end of the night.

The foil creation: Sadie Seal

So many ideas here! It was tough to choose, but I settled on Sadie Seal, one of the circus animals on offer in the Kids’ Korner section.

In her introduction, Conny said to use things that were lying around the house to construct our decorations, so I rounded up a bunch of felt, foam balls, pompoms, and other supplies I had left over from a Halloween costume I never made. I already had a roll of heavy-duty foil in my cabinet. The instructions were not very detailed, as you can see from the photos below, but I did my best.

Making the “mouth” was not easy. Once I cut off the extra foil, I was left with a hard, solid lump of metal that was sharp and nearly impossible to shape.

No guidance either on how to make the flippers. My first attempt gave her absurdly long arms; then I shortened them so much they didn’t touch the floor; and then went with my imperfect third try. I pinned the flippers on the body, cut some eyes out of black felt and pinned those on too. I couldn’t find any ribbon for her neck … so … voila!

I was disappointed at first. It took me about 40 minutes to make this odd little bird-like creature and she didn’t look like the picture at all. But … I took her home on Easter weekend to show her to my gathered family. Once she had ridden with me in the car for 2.5 hours, looking at me with her little felt eyes, I felt like we’d bonded. Plus, everybody thought she was cute. (Mom thought she looked like a turtle.)

*I promise: all extra foil scraps from this project were duly recycled! But I’m not recycling Sadie any time soon. I’m pretty fond of her now. She’s staying on my desk.

But then, as I was browsing our library catalog, I came across 401 Party and Holiday Ideas from ALCOA (Aluminum Company of America, 1971) in our

But then, as I was browsing our library catalog, I came across 401 Party and Holiday Ideas from ALCOA (Aluminum Company of America, 1971) in our

But this 1971 recipe just called for an 8-inch cake pan in a regular oven, and that’s what I used. I was making this in my mom’s kitchen, so I got to use the sifter that had belonged to her mom. Mom told me we had relatives from County Kerry, too.

But this 1971 recipe just called for an 8-inch cake pan in a regular oven, and that’s what I used. I was making this in my mom’s kitchen, so I got to use the sifter that had belonged to her mom. Mom told me we had relatives from County Kerry, too.