The Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2020-2021 travel grants. Our research centers annually award travel grants to students, scholars, and independent researches through a competitive application process. We extend a warm congratulations to this year’s awardees. We look forward to meeting and working with you!

The Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2020-2021 travel grants. Our research centers annually award travel grants to students, scholars, and independent researches through a competitive application process. We extend a warm congratulations to this year’s awardees. We look forward to meeting and working with you!

Please note that due to widespread travel restrictions, the dates for completing travel during this grant cycle have been extended through December 2021.

Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture (Mary Lily Research Grants):

Dena Aufseeser, Faculty, Department of Geography and Environmental Systems, University of Maryland, “Family Labor, Care, and Deservingness in the US.”

Elvis Bakaitis, Adjunct Reference Librarian, The Graduate Center, CUNY, “The Queer Legacy of Dyke Zines.”

Emily Larned, Faculty, Art and Art History, University of Connecticut, “The Efemmera Reissue Project.”

Sarah Heying, Ph.D. candidate, University of Mississippi, “An Examination of the Relationship Between Reproductive Politics and Southern Lesbian Literature Since 1970.”

Susana Sepulveda, Ph.D. candidate, Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, University of Arizona, “Travesando Chicana Punk”, an examination of Chicana punk identity formations through the production of cultural texts.

Tiana Wilson, Ph.D. candidate, University of Texas at Austin, “No Freedom Without All of Us: Recovering the Lasting Legacy of the Third World Women’s Alliance.”

John Hope Franklin Center for African and African American History and Culture:

Brandon Render, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History, University of Texas at Austin, “Color-Blind University: Race and Higher Education in the Twentieth Century.”

Erin Runions, Faculty, Department of Religious Studies, Pomona College, “Religious Instruction of Slaves on Fallen Angels and Hell in the Antebellum Period.”

Katherine Burns, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History, University of Edinburgh, “‘Keep this Unwritten History:’ Mapping African American Family Histories in ‘Information Wanted’ Advertisements, 1880-1902.”

Leonne Hudson, Faculty, Department of History, Kent State University, “Black American in Mourning: Their Reactions to the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln.”

Matthew Gordon, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History, University of Georgia, “American Memory and Martin Luther King, 1968-1983.”

Michael LeMahieu, Faculty, Department of English, “Post ‘54: The Reconstruction of Civil War Memory in American Literature after Brown v. Board.”

Harry H. Harkins T’73 Travel Grants for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender History:

Amanda Stafford, Ph.D. candidate, School of History, University of Leeds, “The Radical Press and the New Left in Georgia, 1968-1976.”

Caitlyn Parker, Ph.D. candidate, American Studies Department, Purdue University, “Lesbians Politically Organizing Against the Carceral State from 1970-2000.”

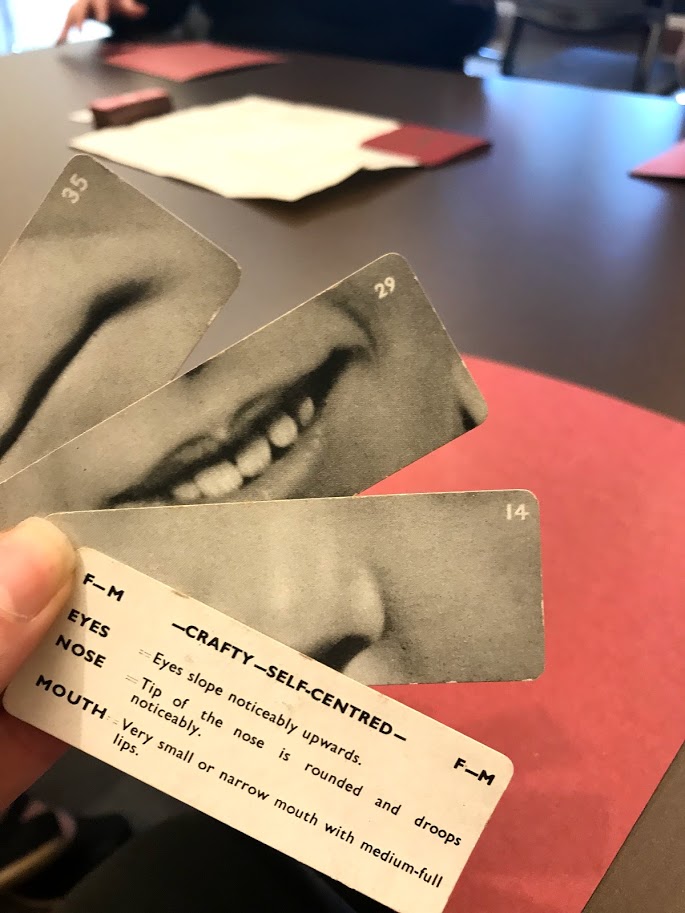

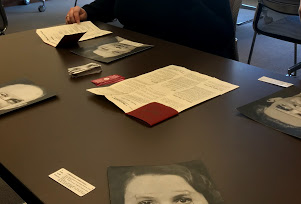

John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History:

Andrew Wasserman, Independent Scholar, “The Public Art of Public Relations: Creating the New American City.”

Austin Porter, Faculty, Department of Art History and American Studies, Kenyon College, “Bankrolling Bombs: How Advertisers Helped Finance World War II.”

Elizabeth Zanoni, Faculty, Department of History, Old Dominion University, “Flight Fuel: A History of Airline Cuisine, 1945-1990.”

Hossain Shahriar, Ph.D. candidate, Department of Business Administration, School of Economics & Management, Lund University, “Gender Transgressive Advertising: A Multi-Sited Exploration of Fluid Gender Constructions in Market-Mediated Representations.”

Jesse Ritner, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History, University of Texas at Austin, “Making Snow: Weather, Technology, and the Rise of the American Ski Industry, 1900-Present.”

Joseph Larnerd, Faculty, Department of Art History, Drexel University, “Undercut: Rich Cut Glass in Working-Class Life in the Gilded Age.”

Katherine Parkin, Faculty, Department of History and Anthropology, Monmouth University, “Asian Automakers in the United States, 1970-1990.”

Meg Jones, Faculty, Communication, Culture & Technology, Georgetown University, “Cookies: The Story of Digital Consent, Consumer Privacy, and Transatlantic Computing.”

Ricardo Neuner, Ph.D. candidate, University of Konstanz, “Inside the American Consumer: The Psychology of Buying in Behavioral Research, 1950-1980.”

Stanley Fonseca, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History, University of Southern California, “Cruising: Capitalism, Sexuality, and Environment in Cruise Ship Tourism, 1930-2000.”

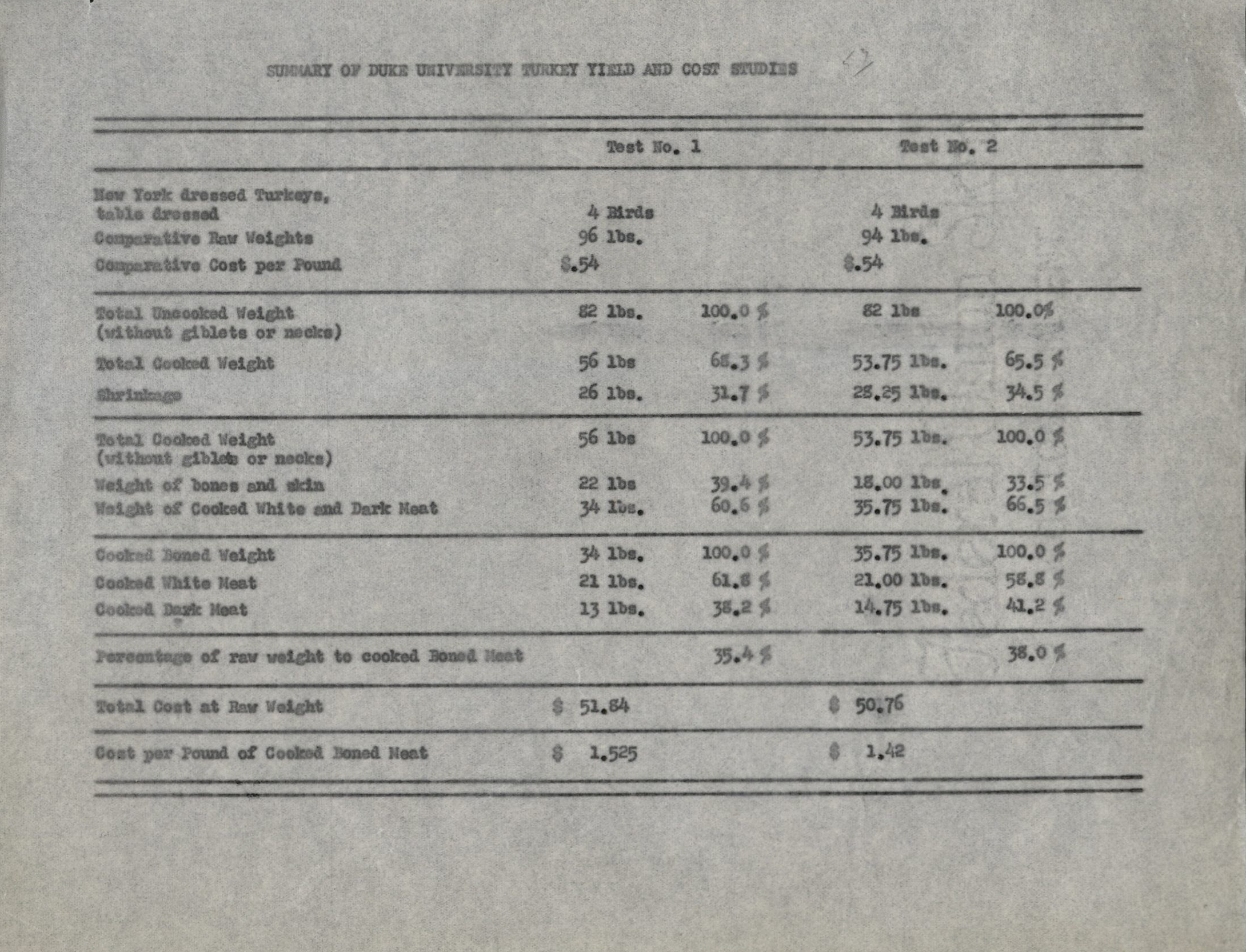

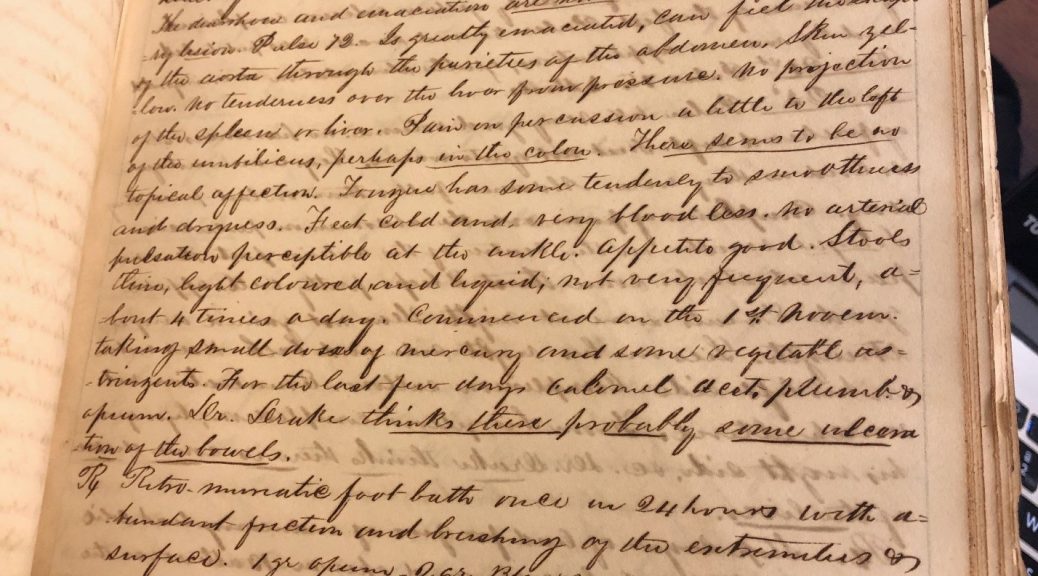

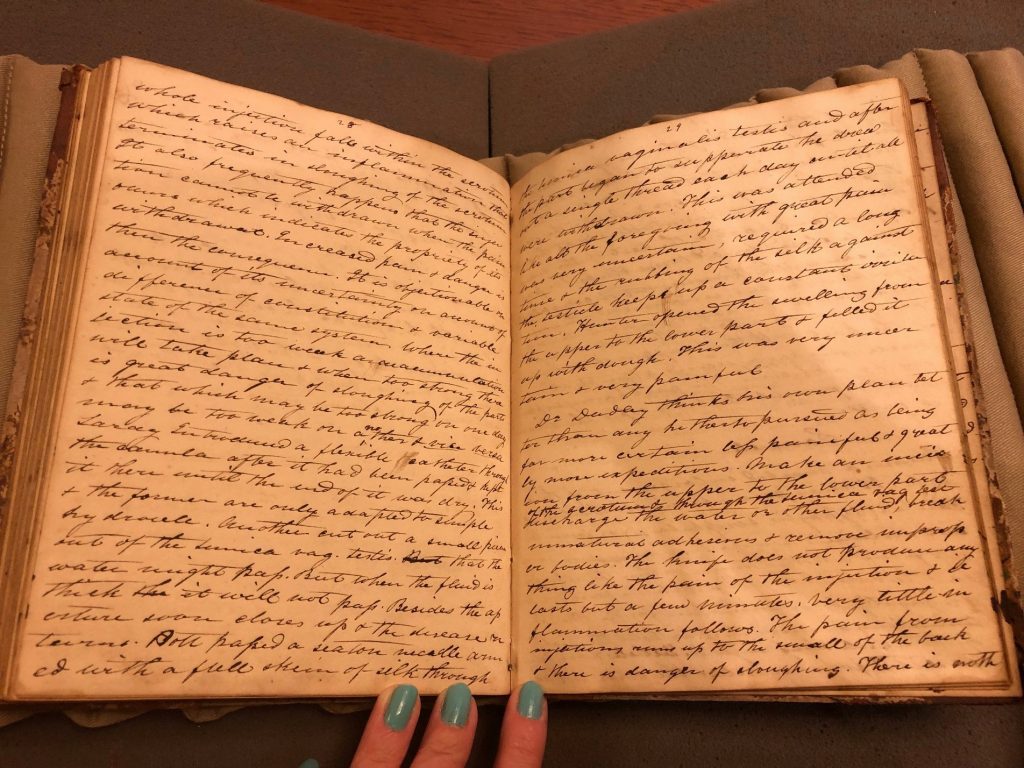

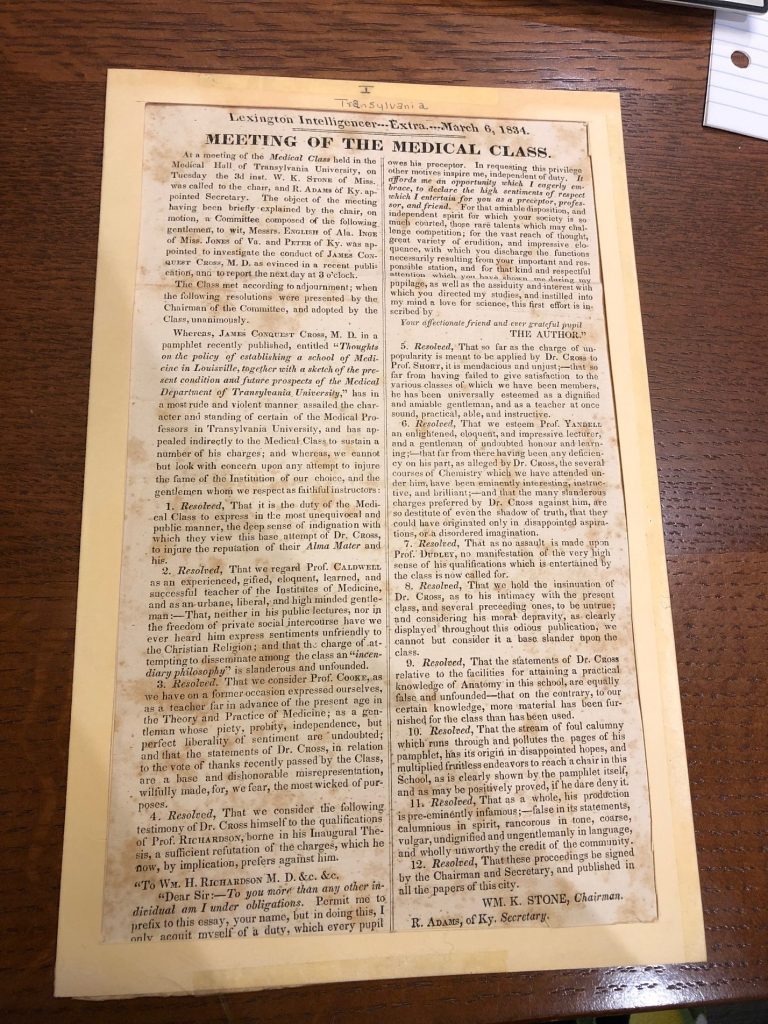

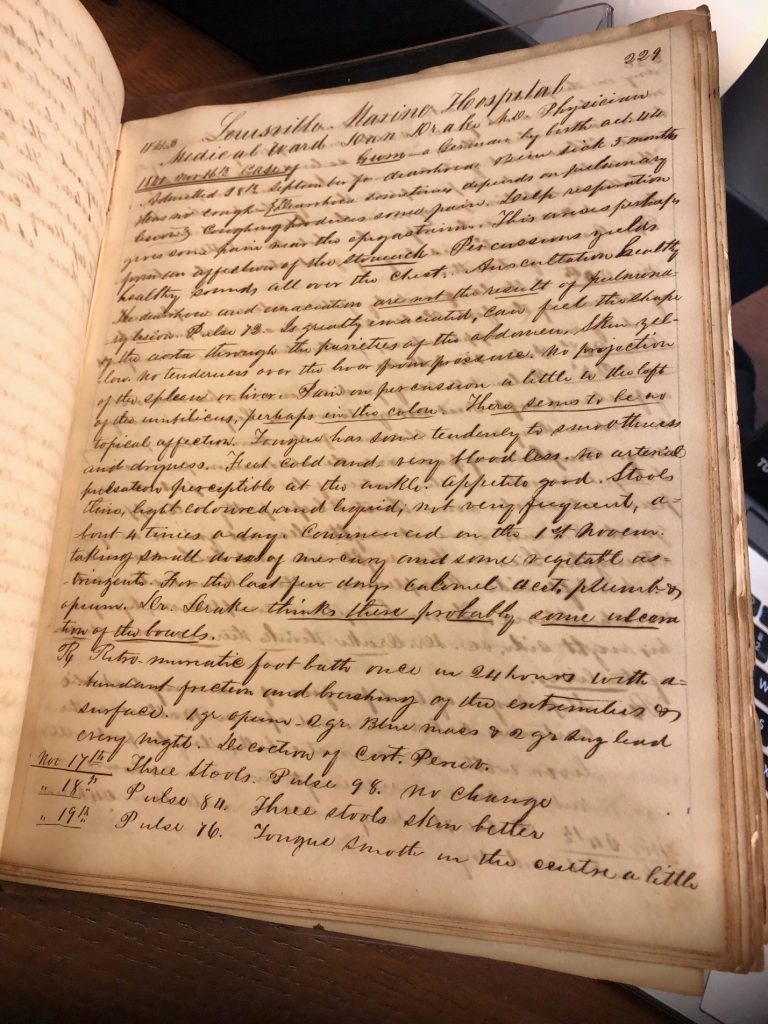

History of Medicine Collections:

Jackson Davidow, Theory and History of Art and Design, Rhode Island School of Design, “Picturing a Pandemic: South African AIDS Cultural Activism in a Global Context.”

Lisa Pruitt, Faculty, Department of History, Middle Tennessee State University, “Crippled: A History of Childhood Disability in America, 1860-1980.”

Morgan McCullough, Ph.D. candidate, Lyon G. Tyler Department of History, William and Mary, “Material Bodies: Race, Gender, and Women in the Early American South.”

Human Rights Archive:

Andrew Seber, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History, University of Chicago, “Neither Factory nor Farm: The Fallout of Late-Industrial Animal Agriculture in America, 1970-2000.”

Eugene (Charlie) Fanning, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History, University of Maryland, College Park, “Empire of The Everglades: A Global History of Agribusiness, Labor, and the Land in 20th Century South Florida.”

Jennifer Leigh, Ph.D. candidate, Department of Sociology, New York University, “Public Health vs. Pro-gun Politics: The Role of Racism in the Silencing of Research on Gun Violence, 1970-1996.”

Richard Branscomb, Ph.D. candidate, Department of English, Carnegie Mellon University, “Defending the Self, Preserving Community: Gun Rights, Paramilitarization, and the Radical Right, 1990-2005.”