Post contributed by Tessel Veneboer, Ph.D. candidate, Department of Literary Studies, Ghent University.

Veneboer received a Mary Lily Research Travel Grant, 2023-2024. This piece is excerpted and adapted from Veneboer’s longer piece “Bad Sex,” published in Extra Intra Reader 3: Swallowed Like a Whole, which was edited by Rosie Haward, Clémence Lollia Hilaire and Harriet Foyster, (Gerrit Rietveld Academie & Sandberg Instituut, 2024).

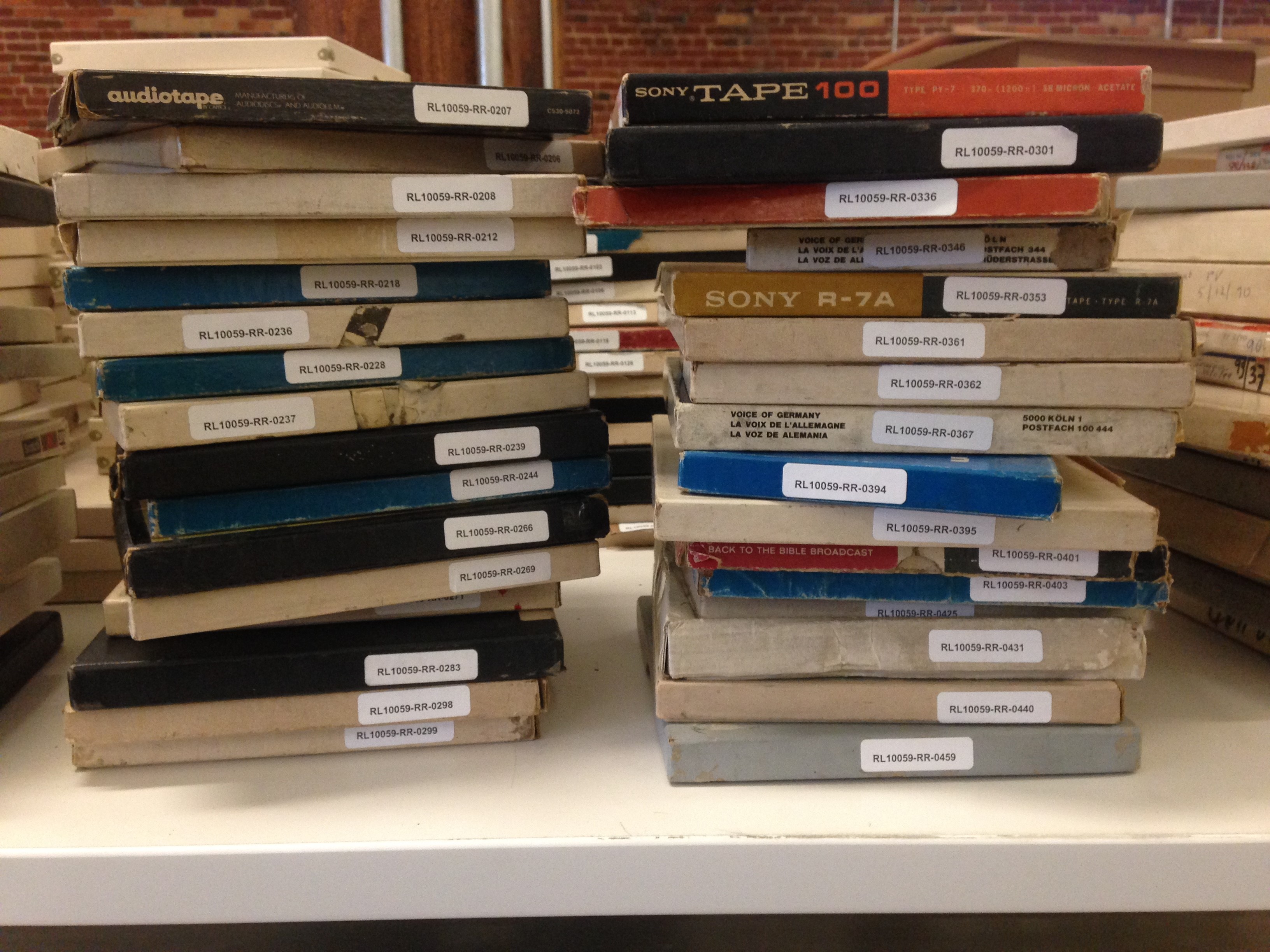

As part of my doctoral research, I spent four weeks at Duke University studying the Kathy Acker Papers and other collections at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History & Culture. I work on the relationship between sex and literary form. In particular, the question of the optimism-pessimism divide among feminists about the givenness of the sexual imagery under patriarchy: the pornographic imagination. After sharing my interests with Kelly Wooten, archivist at the Sallie Bingham Center, she suggested I look at the archives of several anti-pornography activists including Dorothy “Cookie” Teer. This diversion from the Acker papers went on to consume much of my research time as I became more and more absorbed in the anti-pornography materials.

Flipping through newspaper clippings, personal correspondence, logistics for conferences and teach-ins, drafts of lectures and manifestos in the Teer Papers, I began to see that disagreements among feminists over the role of pornography, sexual violence, and censorship are not only part of a dispute about what feminists want or should want from sex, but contain perhaps a more fundamental disagreement: the definition of “sex” itself. Is sexuality simply an activity that should and can be reimagined by feminists or should we analyse sex as part of human nature, that is: as subjectivity itself? And if the latter, can there be any authenticity of sexual desire for women in a patriarchal society?

Among the anti-porn materials in the archive, I found an extensively annotated draft of a paper titled ”Sex Resistance in Heterosexual Arrangements.” A manifesto of sorts, the paper was authored by the Southern Women’s Writing Collective, alternatively known as Women Against Sex (WAS). The WAS group was closely affiliated with Women Against Pornography (WAP) who were active in New York City, under the wings of Andrea Dworkin and Catherine McKinnon. The WAS group met WAP in 1987 at the “Sexual Liberals and the Attack on Feminism” conference at New York University, where WAS presented their manifesto for the first time.

The advertising poster of the conference asks: “Who are the sexual liberals? What are they doing to feminism? Why do they defend pornography? What do they mean by ‘freedom’?” In the manifesto, the WAS members make a case against the pro-sex attitude that aims to rethink and reclaim female sexuality by emphasising the multiplicity of pleasures. To simply change the representation of sexuality does not resolve the association of sex with subordination for the WAS group. For them, sex-positive feminism follows a patriarchial logic that naturalises sexuality as an animalistic force and thus can keep women “under the spell” of sexuality. Women Against Sex asks: what if we resist compulsory sexuality?

The conference materials in the archive contain many drafts and internal disagreements over the WAS manifesto, but the rationale is clear: the only function of sex is the subordination of women and therefore “the practice of sexuality” must be resisted. This “sex resistance” movement aligns with Valerie Solanas’s proposal in the S.C.U.M. manifesto to create an “unwork force” of women who will take on jobs in order not to work at the job, to work slowly, or to get fired. To engage in ‘”sex resistance” is to refuse the idea that woman is, before all else, a sexual being who must realise the potential to enjoy sex. In the manifesto WAS proposes two alternatives: feminist celibacy and “deconstructive lesbianism.” They emphasize the difference between religious celibacy–the “vow”–and celibacy as politicized by feminist thought:

She resists on three fronts: she resists all male-constructed sexual needs, she resists the misnaming of her act as prudery and she especially resists the patriarchy’s attempt to make its work of subordinating women easier by consensually constructing her desire in its own oppressive image.[i]

WAS adds that, historically, women have long been practising deconstructive lesbianism and radical celibacy. For example, when a woman temporarily abstains from sex after sexual assault or when women live together without being sexually involved. This sex resistance paper thus argues that feminist celibacy is not new but that this type of abstinence has not been politicised as sabotage.

In a letter to Women Against Pornography, a WAS member explains that the disturbing nature of sex–-what they call woman’s “self-annihilation” as the social paradigm of our sexuality–-is in fact the definition of sex: if it doesn’t subordinate women it’s not sex. This claim is strangely close to queer theorist Leo Bersani’s proposal in “Is the Rectum a Grave?” (1987) that sexuality destabilizes any coherent sense of self as the boundaries between self and other are disturbed. Both Dworkin and Bersani refuse to romanticise sex and, as such, denaturalise sex.

The argument for radical celibacy in the “Sex resistance in heterosexual arrangements” article was ambivalently received at the 1987 conference hosted by Women Against Pornography in New York City. WAP member Dorchen Leidholdt, for example, writes to WAS that she fears the sex resistance proposal would undermine the credibility of the anti-pornography movement as a whole. Andrea Dworkin, however, was intrigued by the politicized celibacy which she found “more radical” than her own proposal to ban all pornography. Only without compulsory heterosexuality, it would be possible to restore, make whole again, what Dworkin calls the ”compromised metaphysical privacy” of woman.

[i] Southern Women’s Writing Collective (Women Against Sex), ‘Sex Resistance in Heterosexual Arrangements’, Sexual Liberals and the Attack on Feminism, New York & London, Teachers College Press, 1990.