Post contributed by Theodore D. Segal, guest contributor1

On September 26, 2020, Duke University announced that the Sociology-Psychology Building on its West Campus was renamed the Wilhelmina Reuben-Cooke Building to recognize Reuben-Cooke’s role as one of the “First Five” Black undergraduates at Duke and her many contributions to the university. A fitting honor, this recognition recalls a different time at Duke, one when Reuben-Cooke’s election as the school’s first Black May Queen stirred controversy.

* * * * * * * * *

Although by 1967 a number of longstanding traditions at Duke had been set aside, the annual practice of crowning a “May Queen” endured. Selection of the “Queen” was a centerpiece of popular “May Day” celebrations, a holiday whose origins date back to the ancient world. Villagers throughout Europe would collect flowers and participate in games, pageants, and dances throughout the day. It became customary to crown a young woman “May Queen” to oversee the festivities. During the early 20th century, selection of a May Queen became common at women’s colleges in the United States and had acquired a special meaning in the South. “The crowning of the May Queen as the ritual incantation of Southern society’s ideal of femininity,” historian Christie Anne Farnham wrote, “was a traditional event at Southern female schools. . . . The queen was usually elected by the students on the basis of ‘sweetness’ and beauty,” Farnham explained, although the father’s status often played a role.

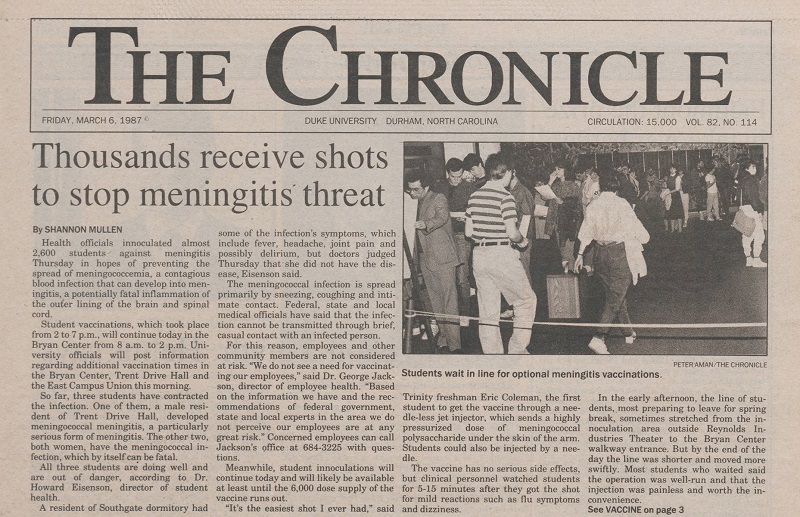

May Queen traditions at Duke dated back to 1921 when the school was still known as Trinity College. The Trinity Chronicle reported that 2000 spectators attended May Day festivities that first year, and that the two-day celebration was spent “in gaiety and amusement.” Undergraduate Martha Wiggins was crowned Queen of May that year. The school newspaper wrote that she, “wore a lovely costume of shimmering white, bearing a corsage of white roses with her golden hair cascading in waves down her back, making a charming picture of perfect grace and absolute loveliness.”

Given this context, it was newsworthy when Wilhelmina Reuben, a member of Duke’s first class of Black undergraduates, was selected as the Woman’s College May Queen in spring 1967. As runners up in the voting, white coeds Mary Earle and Jo Humphreys were designated to serve as Reuben’s “court.” The Associated Press picked up the news, reporting that “Mimi, as she is known to her friends, is a Negro—the first of her race to receive the honor at the women’s[sic] college of the university.” Chosen for her character, leadership, campus service, and beauty, Reuben had been selected May Queen by a vote of students in the woman’s college. A fact sheet on Reuben prepared by Mary Grace Wilson, dean of women, described her as “warm, friendly, perceptive and sensitive to the feelings of others.” Wilson called her “one of the most admired and highly respected students on the campus.” Reuben was a member of the freshman honor society and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa as a junior. A student intern at the State Department, she was listed in “Who’s Who Among Students in American Universities and Colleges. For her part, Reuben was pleased by her selection. “I’m still trying to adjust to it,” she told the Associated Press. “I’ve been walking around in a delightful haze of disbelief and excitement.”

Given this context, it was newsworthy when Wilhelmina Reuben, a member of Duke’s first class of Black undergraduates, was selected as the Woman’s College May Queen in spring 1967. As runners up in the voting, white coeds Mary Earle and Jo Humphreys were designated to serve as Reuben’s “court.” The Associated Press picked up the news, reporting that “Mimi, as she is known to her friends, is a Negro—the first of her race to receive the honor at the women’s[sic] college of the university.” Chosen for her character, leadership, campus service, and beauty, Reuben had been selected May Queen by a vote of students in the woman’s college. A fact sheet on Reuben prepared by Mary Grace Wilson, dean of women, described her as “warm, friendly, perceptive and sensitive to the feelings of others.” Wilson called her “one of the most admired and highly respected students on the campus.” Reuben was a member of the freshman honor society and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa as a junior. A student intern at the State Department, she was listed in “Who’s Who Among Students in American Universities and Colleges. For her part, Reuben was pleased by her selection. “I’m still trying to adjust to it,” she told the Associated Press. “I’ve been walking around in a delightful haze of disbelief and excitement.”

Many at Duke were pleased with the news. Randolph C. Harrison, Jr., an alumnus from Richmond, Virginia, wrote to Douglas Knight, Duke’s president, that the “undergraduates’ choice of Miss Reuben as May Queen attests once more to Duke’s greatness. What a step towards inter-racial accord.”

If Reuben’s election represented progress to some, however, the prospect of a Black May Queen flanked by two white members of her “court” felt like a violation of the established social order to others. Jonathan Kinney, president of the Duke student government, saw the reaction when he had the responsibility of “crowning” the queen and her court. “I kissed all the rest of the panel,” he recalled, “so I kissed [Wilhelmina Reuben]. There were a lot of boos in that stadium at that time.” An anonymous alumnus sent the Duke president pictures of the “pretty May Queens chosen at Peace, St. Mary’s, and Meredith Colleges,” all of whom were white, along with a picture of Reuben, “a colored girl who was chosen May Queen at our Dear Ole Duke University.” The alumnus noted the “deplorable contrast between the May Queens of other colleges and the stunning representative from Duke.” He told Knight “Duke Alumni everywhere were stunned and several in South Carolina had strokes.” One correspondent, identified as a “lifelong, respected citizen of Wilmington, North Carolina,” outlined with exasperation the problems that Reuben’s election was creating at the city’s annual Azalea Festival where May Queens from throughout North Carolina were invited to attend:

The Sprunt’s annual garden party at Orton [Plantation] for the college queens (held for the past 20 years) has been cancelled; the Coastguard Academy, which was supposed to furnish her escort, says they don’t have a colored boy available; the private home in which she was supposed to stay is not now available; and there are all sorts of complications.

“The crowd who elected her has done a disservice to her,” the writer opined, “and placed a no doubt nice girl in an embarrassing situation.”

Finally, two trustees weighed in. C. B. Houck told Knight that he liked and respected “the colored people” and wanted them to have “every opportunity that the white people have.” Still, he thought Reuben’s election was in “bad taste” and that the “East Campus girls were leaning over backwards to be nice.” For Houck, the symbolism was deeply troubling. “To select a colored person for May Queen and have white maids of honor flanking her on either side,” he concluded, “makes for poor and critical relationship [sic] among many people, particularly in the South.” Trustee George Ivey was also deeply concerned. Writing from Bangkok, Thailand, he called Reuben’s selection “very upsetting to me.” Even if the selection was by Duke’s coeds, Ivey regretted “that the University has attracted the type of students that would vote for a Negro girl as a ‘beauty’ to represent the student body. It is nauseating to contemplate.”

By spring 1967, Duke had eliminated most of the school’s de jure discriminatory policies and practices. Reuben’s election as May Queen could be seen as another positive sign of racial progress. But the episode also shined a spotlight on the depth of attachment some still had to traditional racist ideas. These attitudes would become even more pronounced in the months to come as Black student activism accelerated on campus.

1Ted Segal is a Duke graduate (A.B. 1977), retired lawyer, and a board member of the Center for Documentary Studies at the school. His book, POINT OF RECKONING: The Fight for Racial Justice at Duke University, will be published by Duke University Press in February 2021. Special thanks to the Duke University Archives for preserving the historical records quoted in this piece and for making them readily accessible.